Tutorials

Beginners guide

Run your first project

You can check a sequence of pages to learn how to run your first project with our Getting Started training. From installation process and formatting your model files up to the long-term planning of your project.

Click HereMust-Read Articles

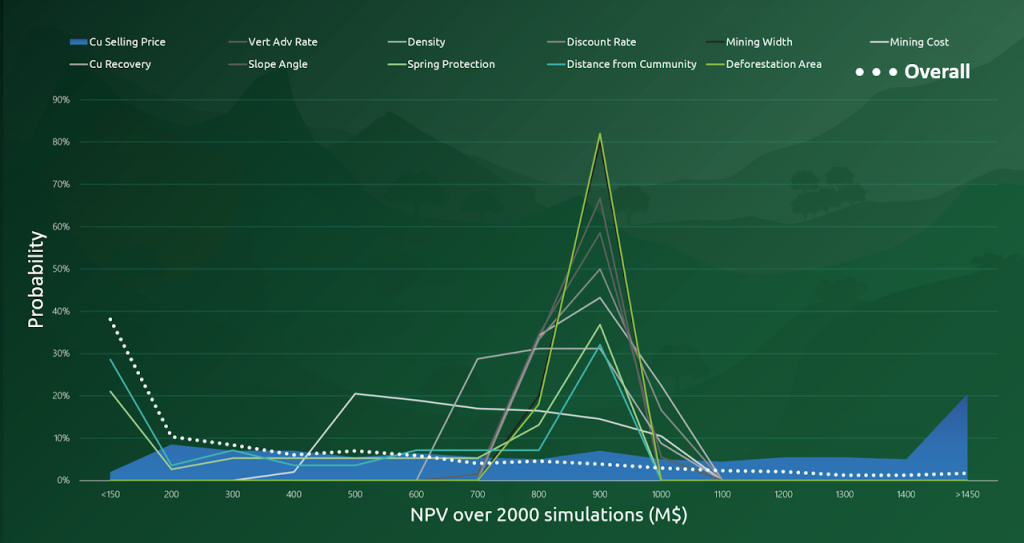

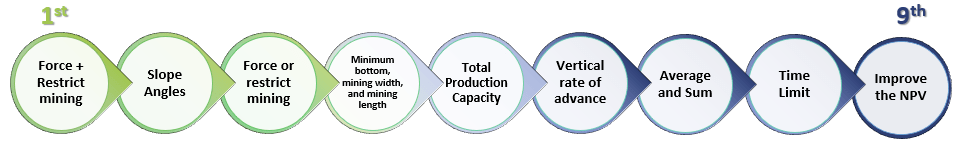

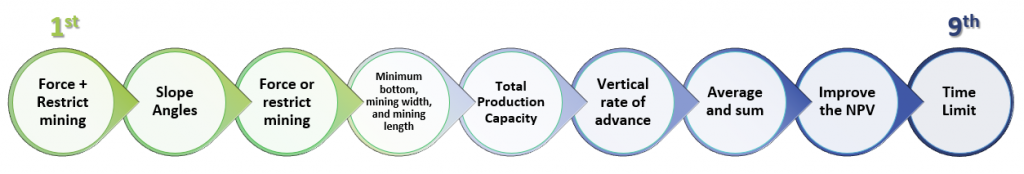

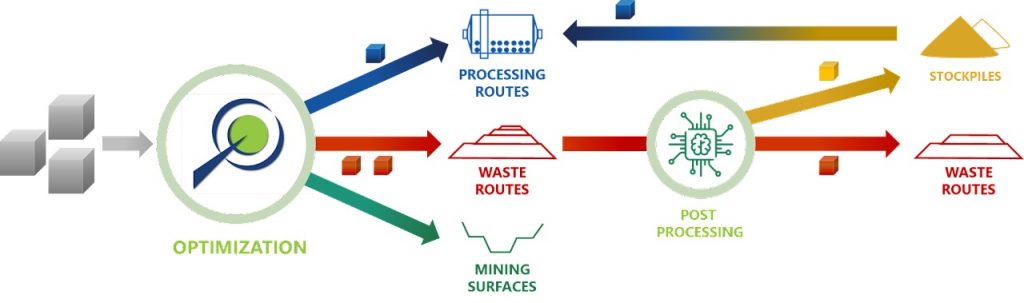

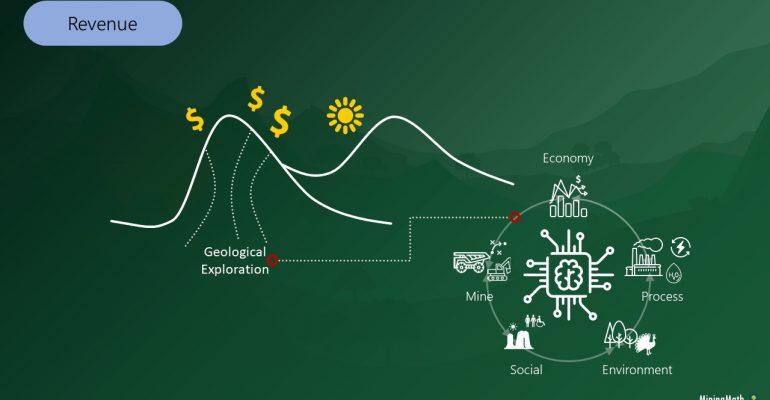

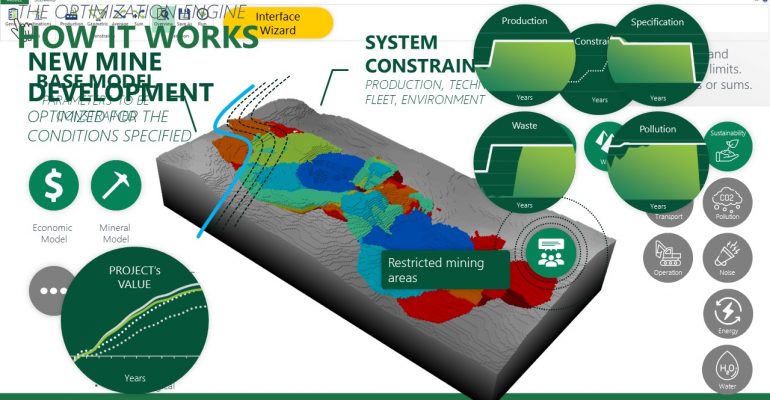

In order to take the maximum of MiningMath’s Optimization we recommend this flow through our Knowledge Base. It will guide you step-by-step in order to integrate multiple business’ areas and to improve your strategic analysis through risk assessments unconstrained by step-wise processes.

Set up and first run

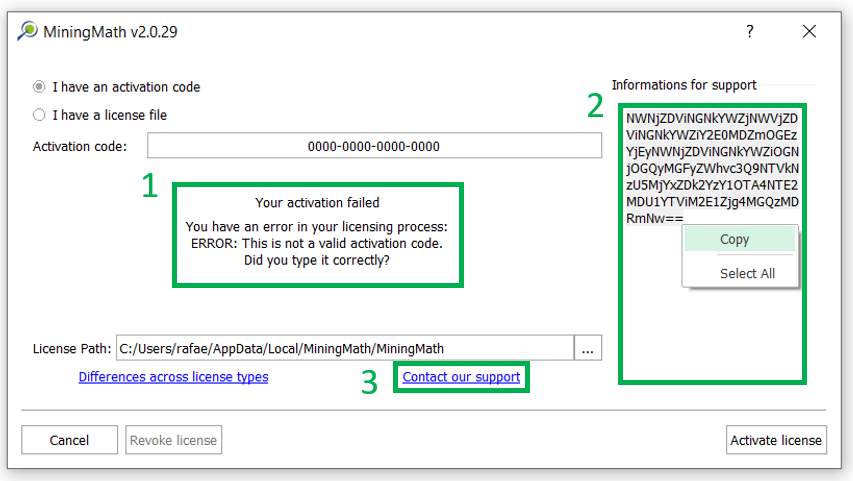

Quick Check: Here you’ll have all the necessary instructions to install, activate and run MiningMath.

How to run a scenario: Once everything is ready, it’s time to run your first scenario with MiningMath so you can familiarize with our technology!

Find new results

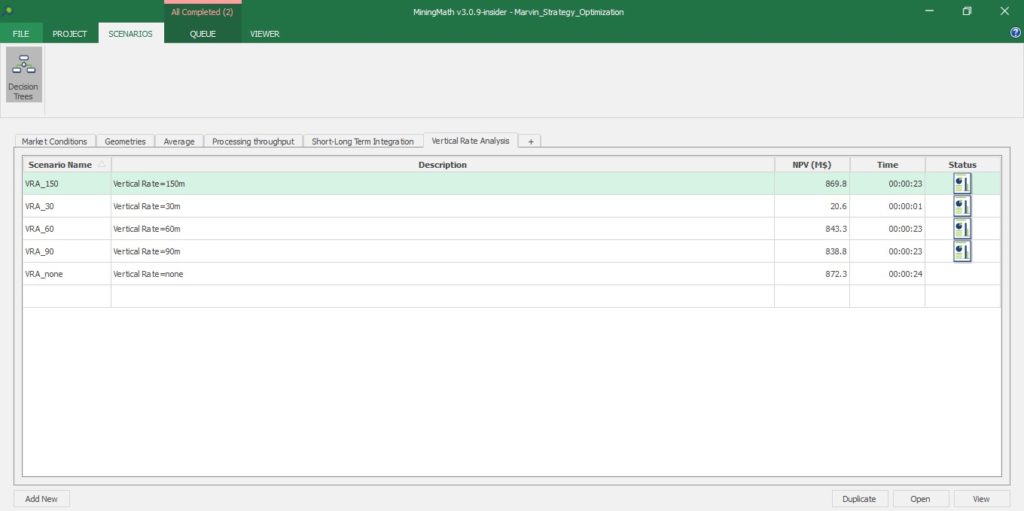

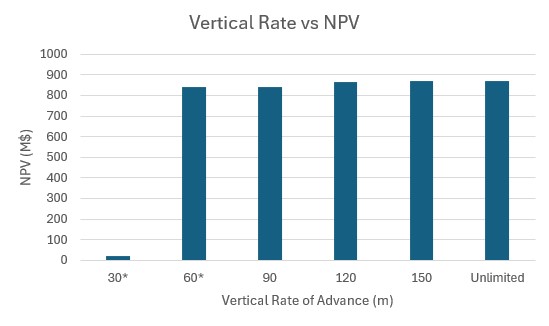

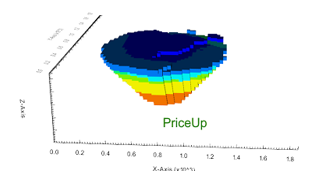

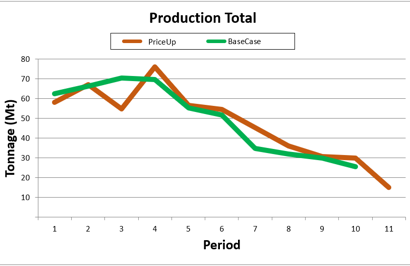

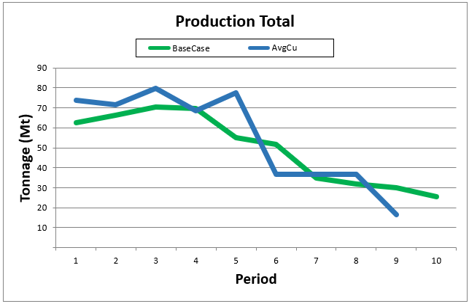

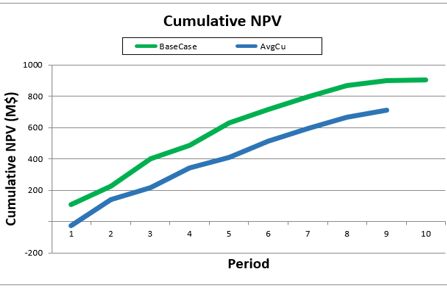

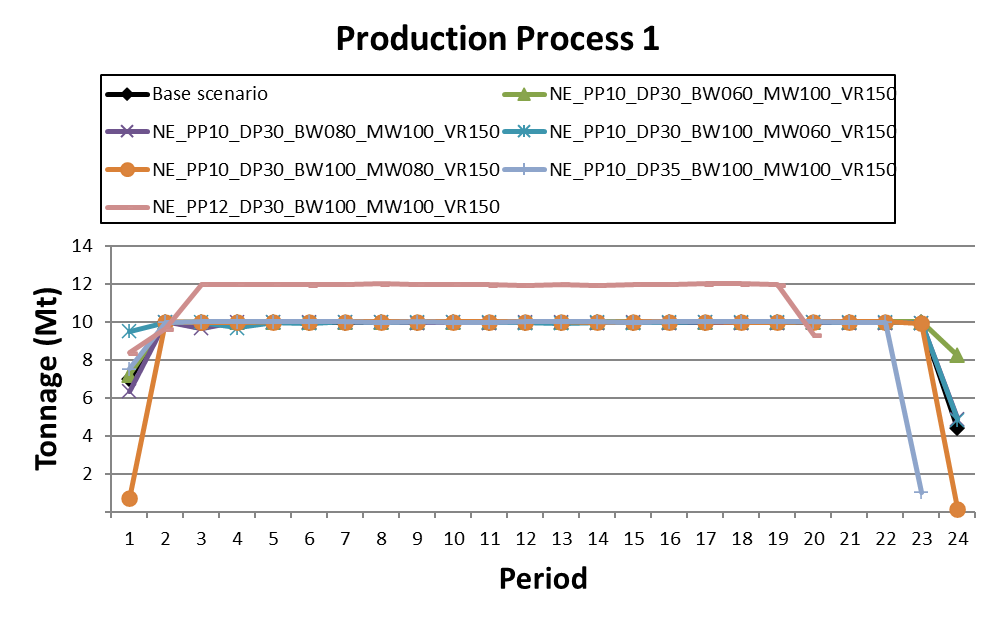

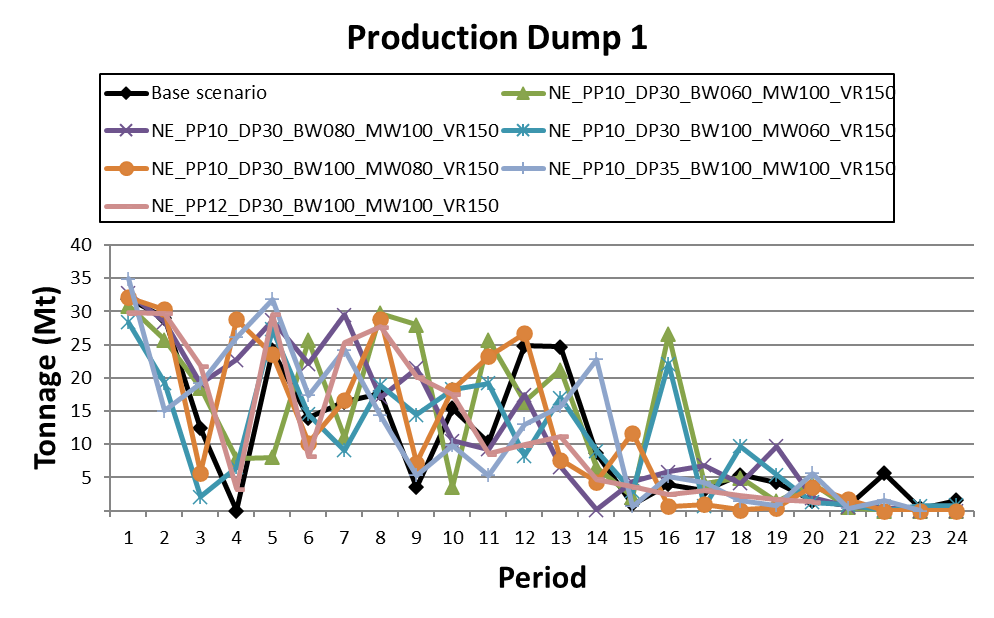

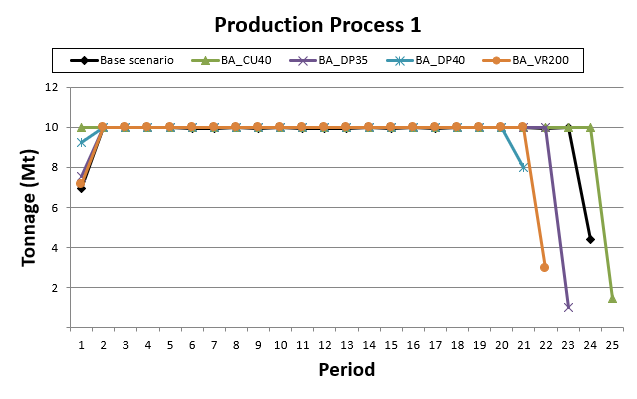

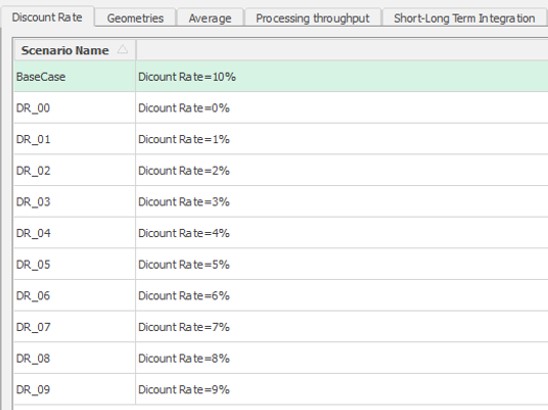

Playing with pre-defined scenarios: Each change in a scenario opens a new world of possibilities, therefore, it’s time to understand a little more about and see it in practice, playing with pre-defined scenarios.

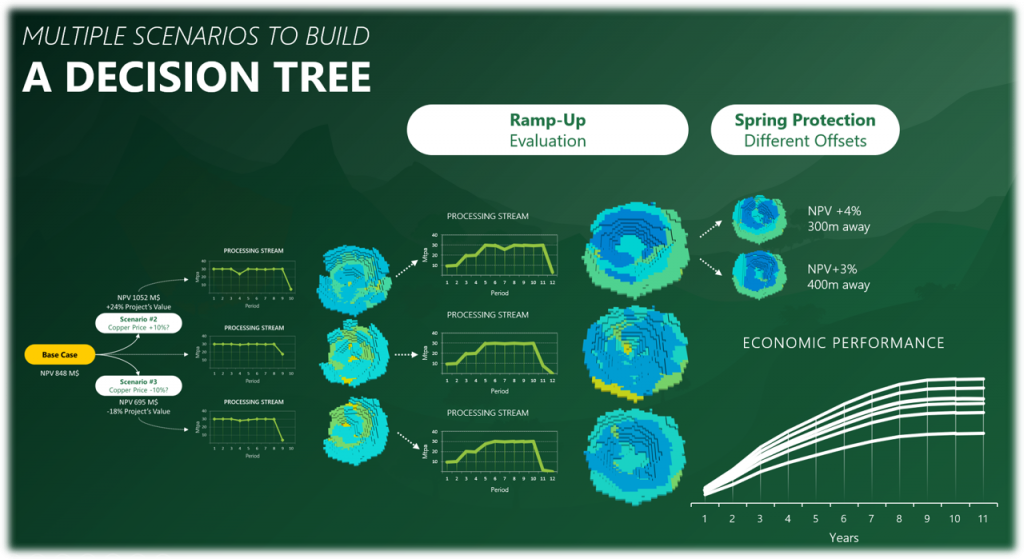

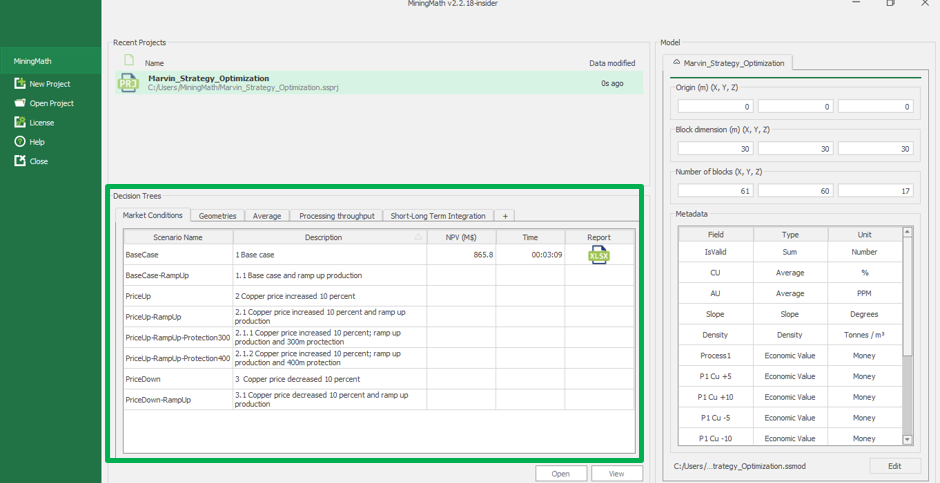

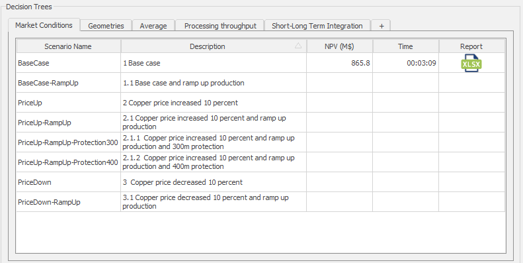

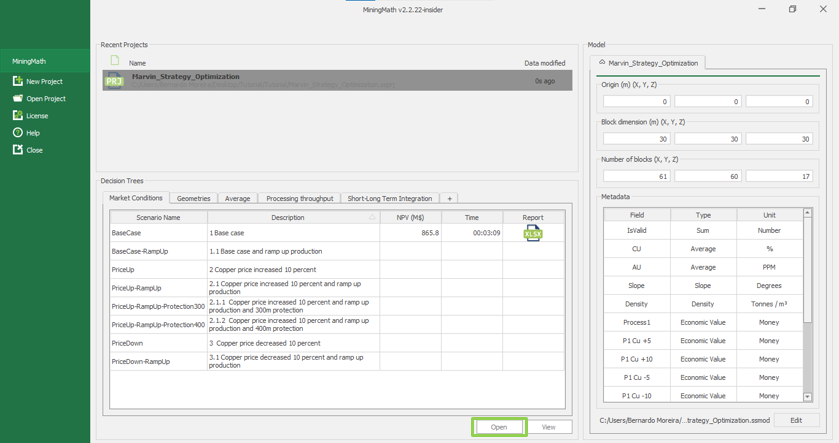

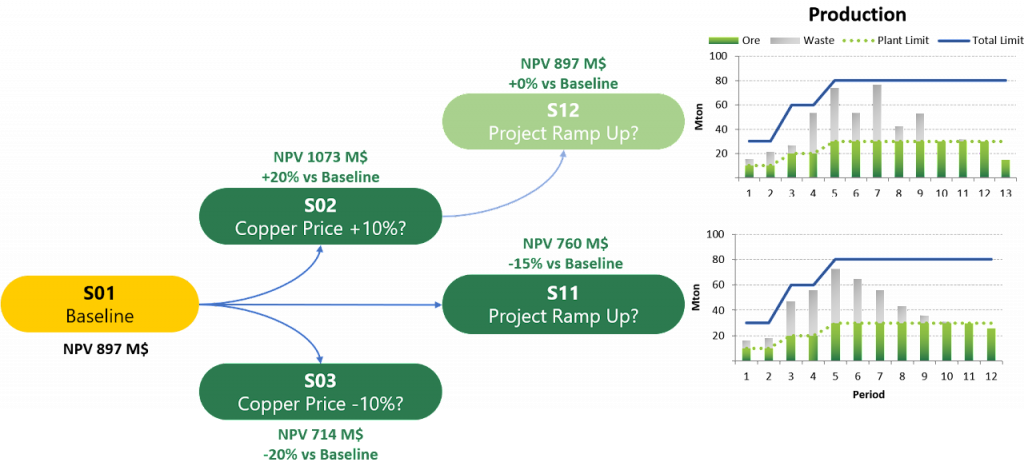

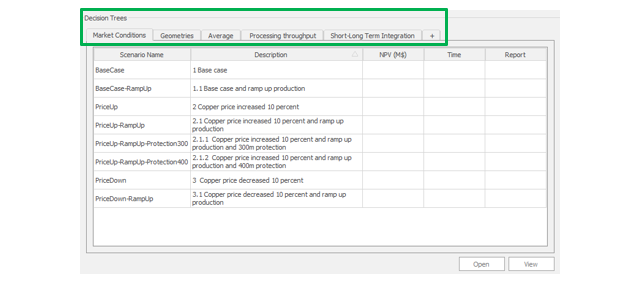

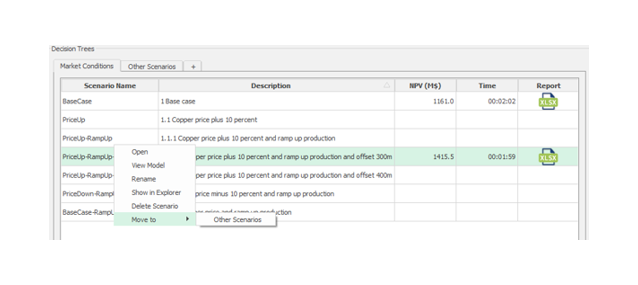

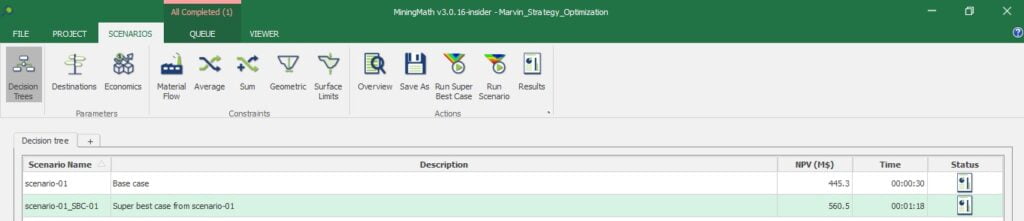

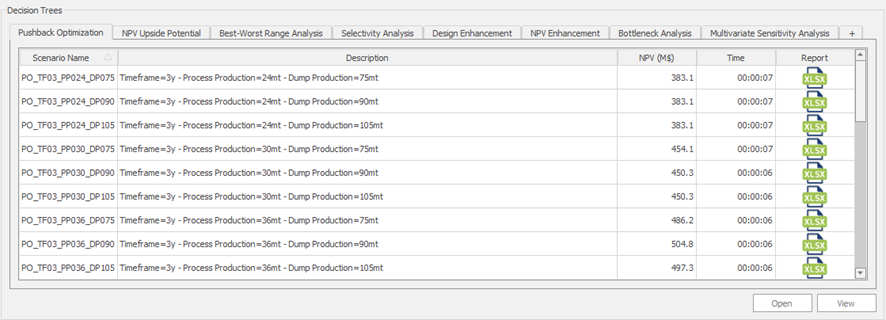

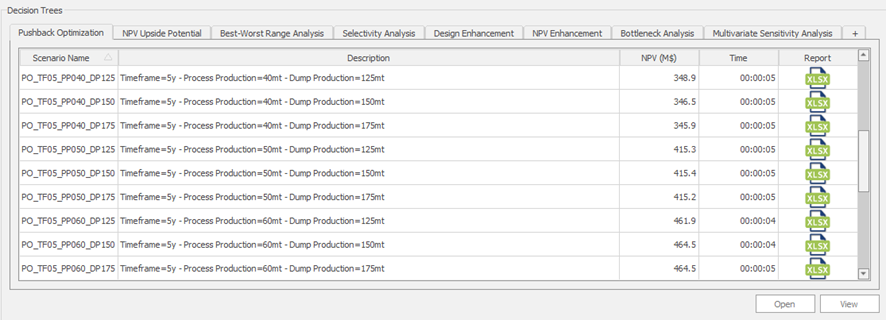

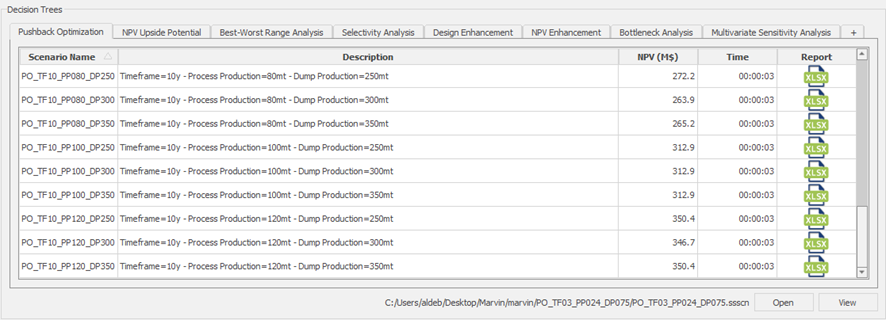

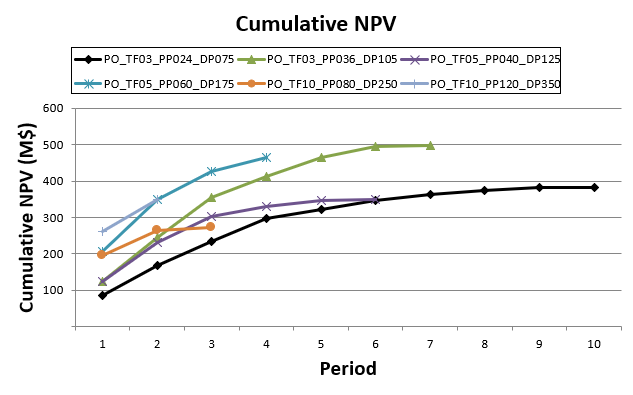

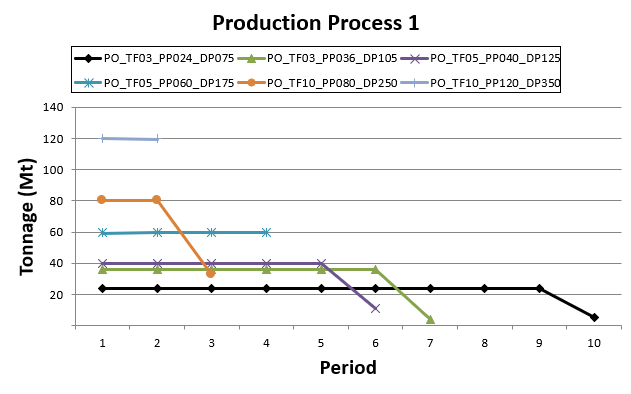

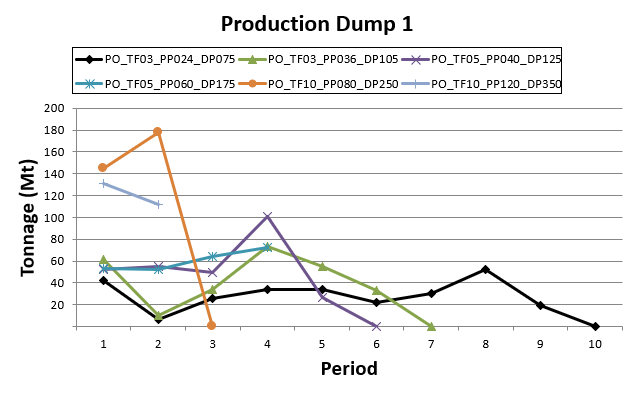

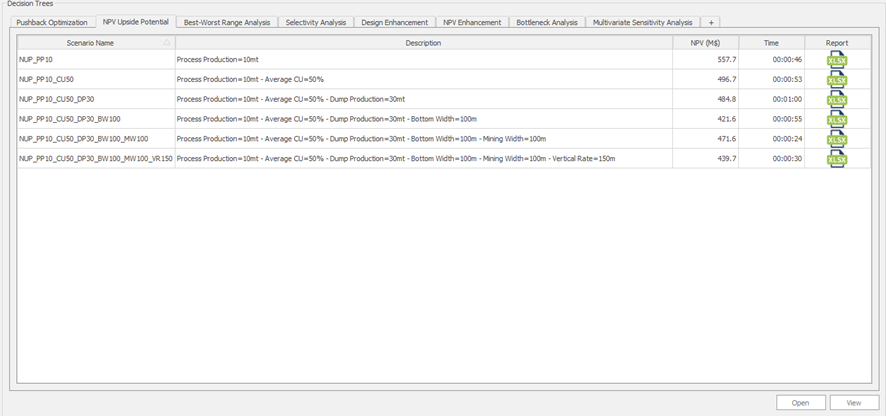

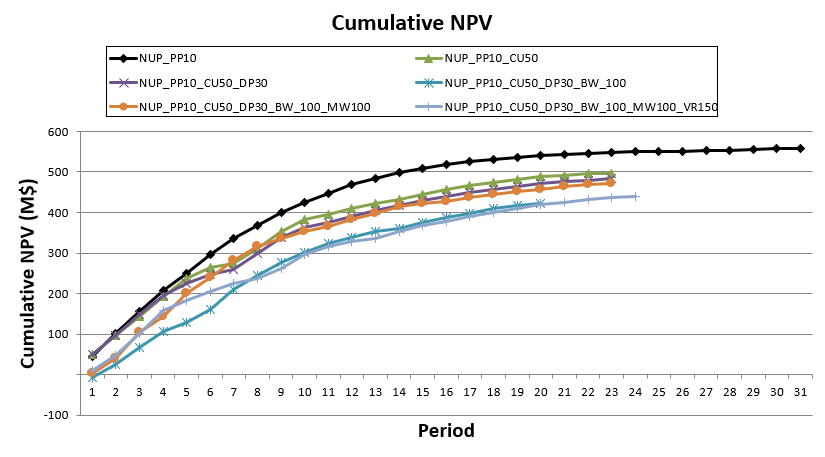

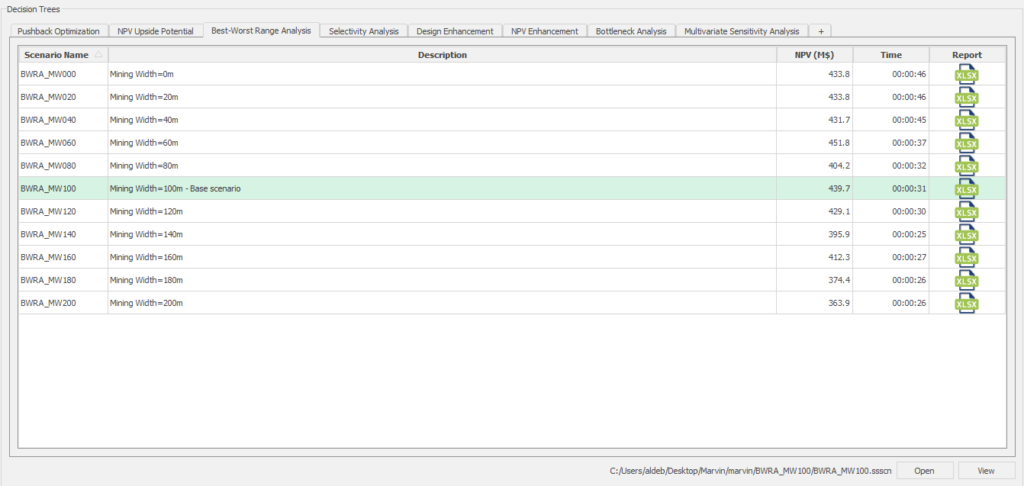

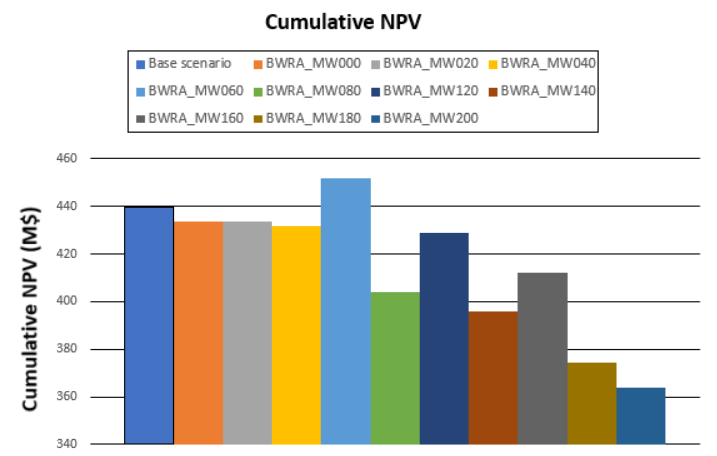

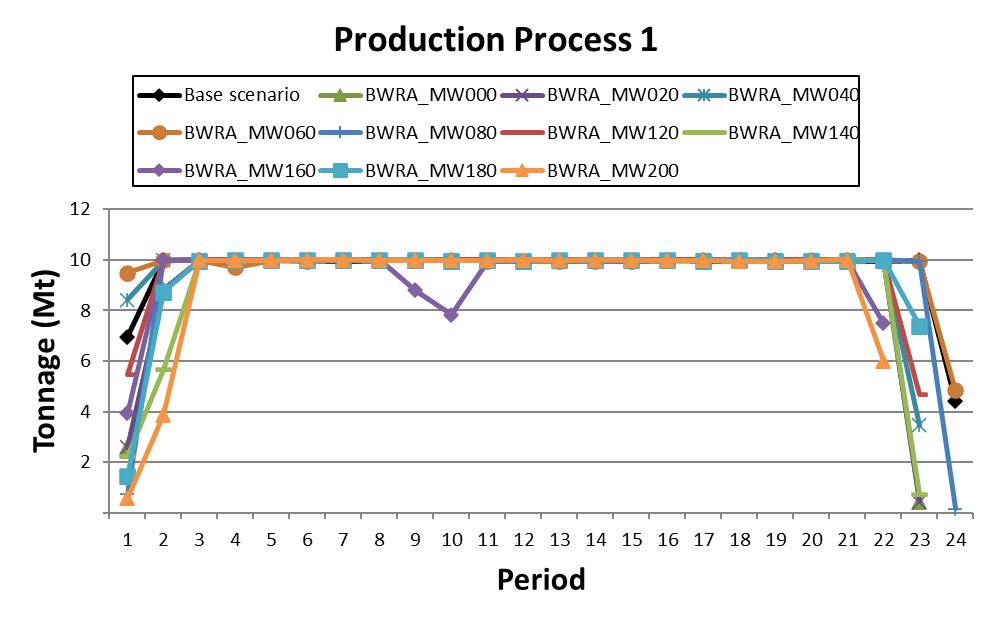

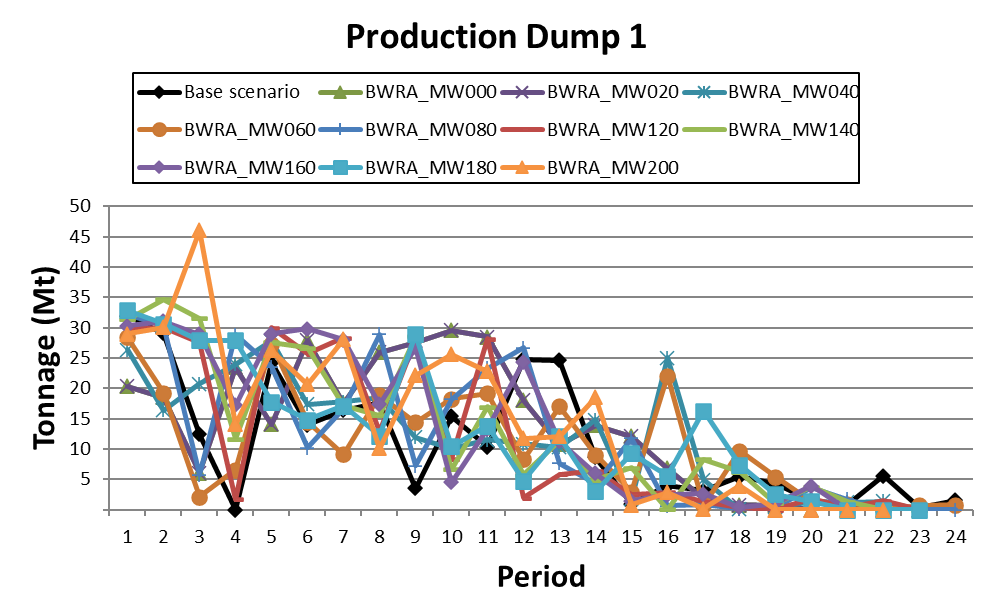

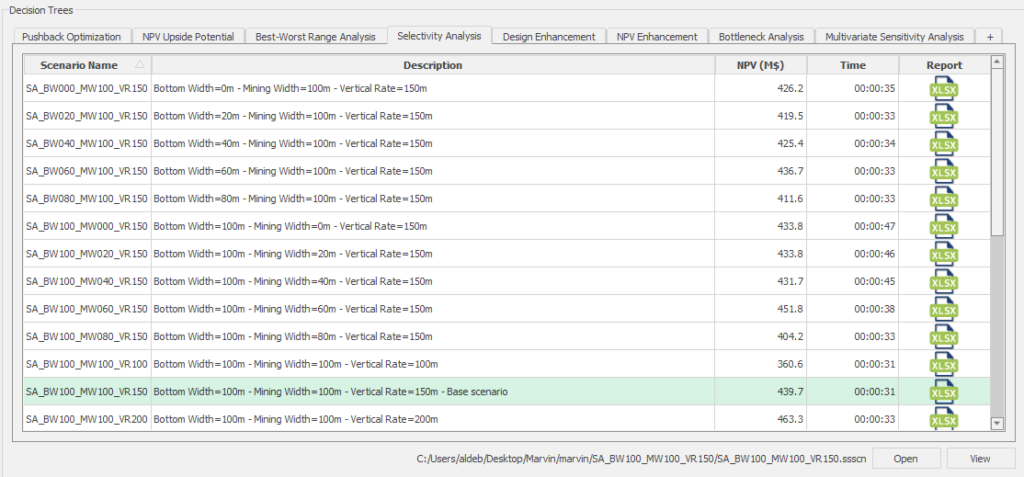

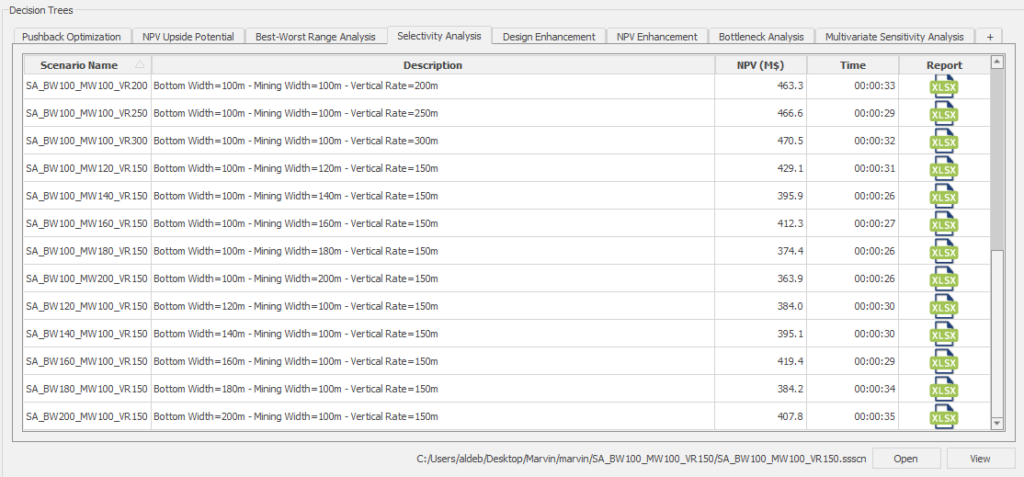

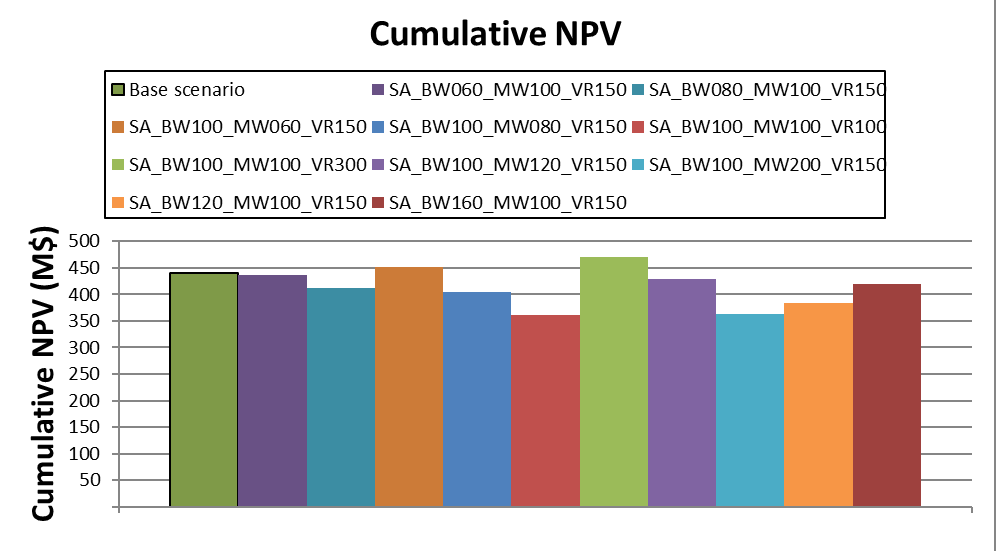

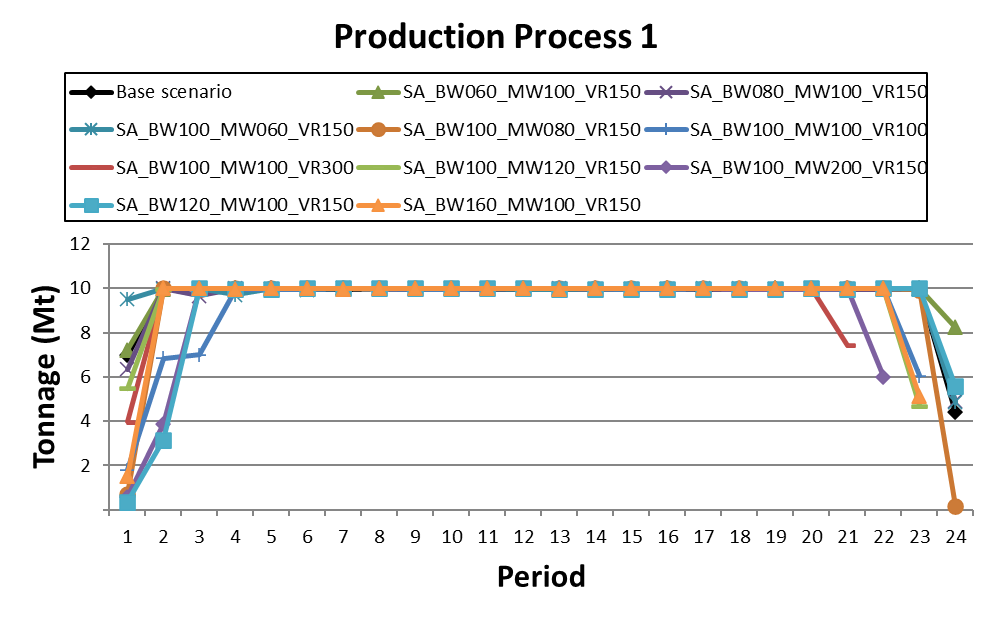

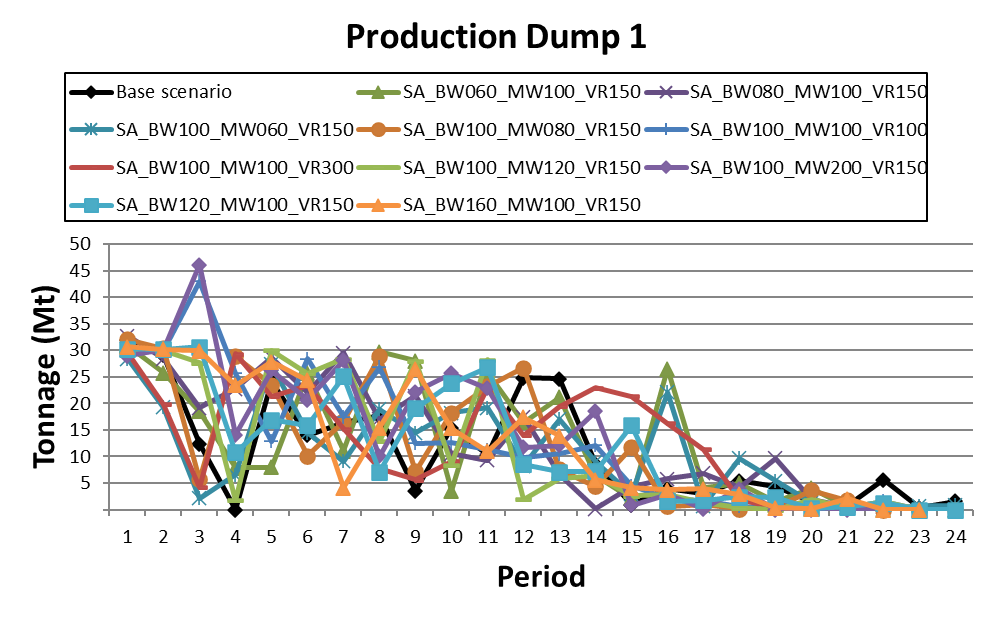

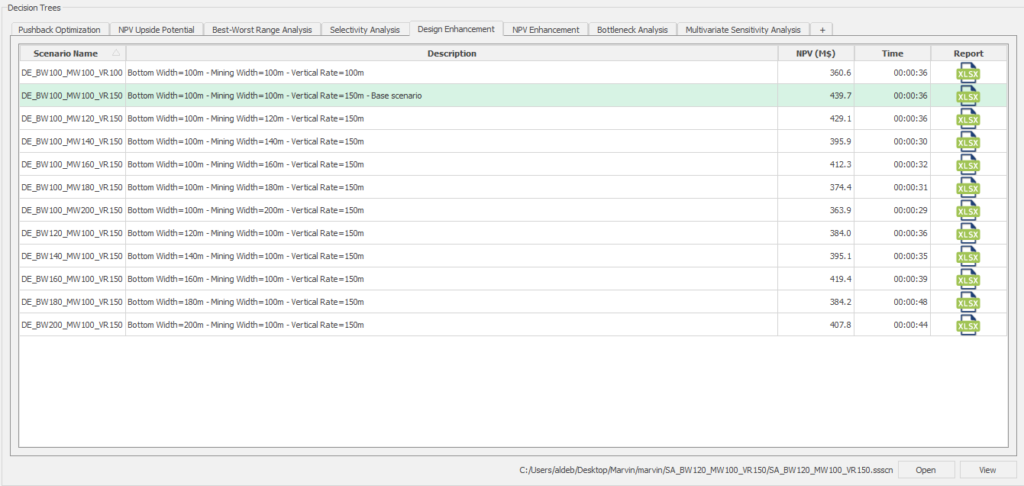

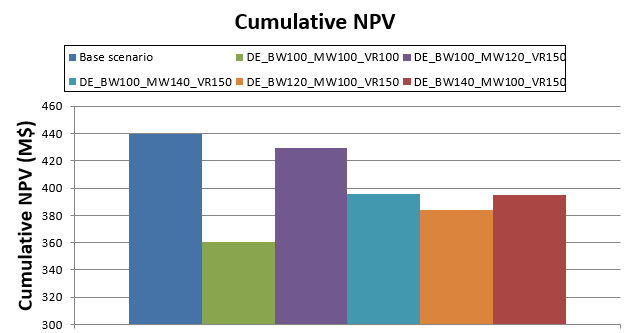

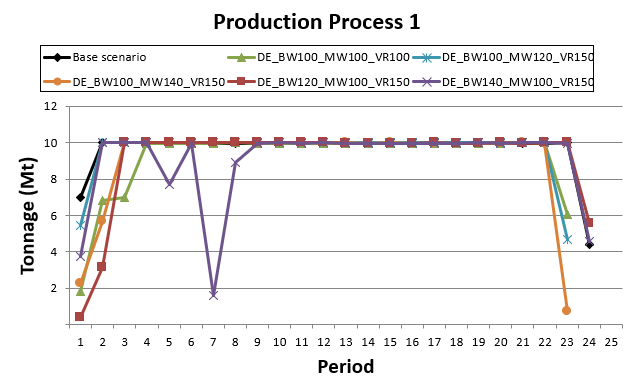

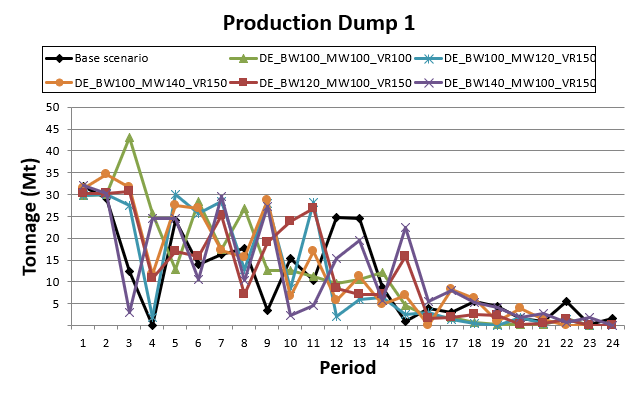

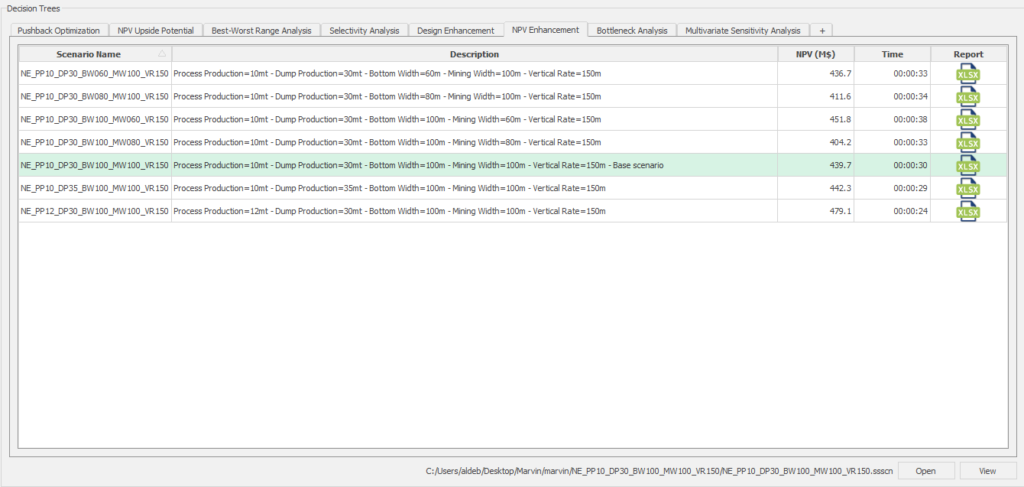

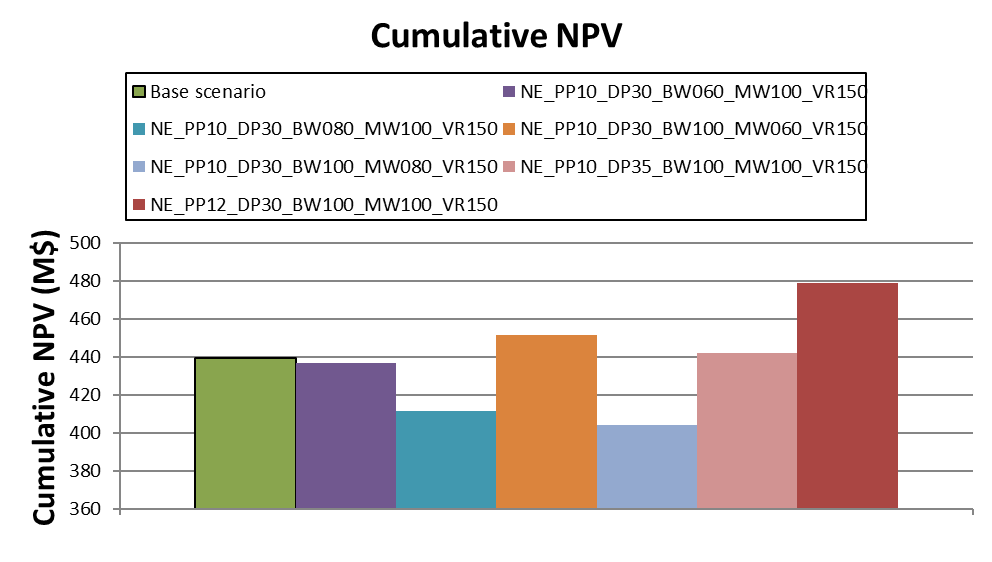

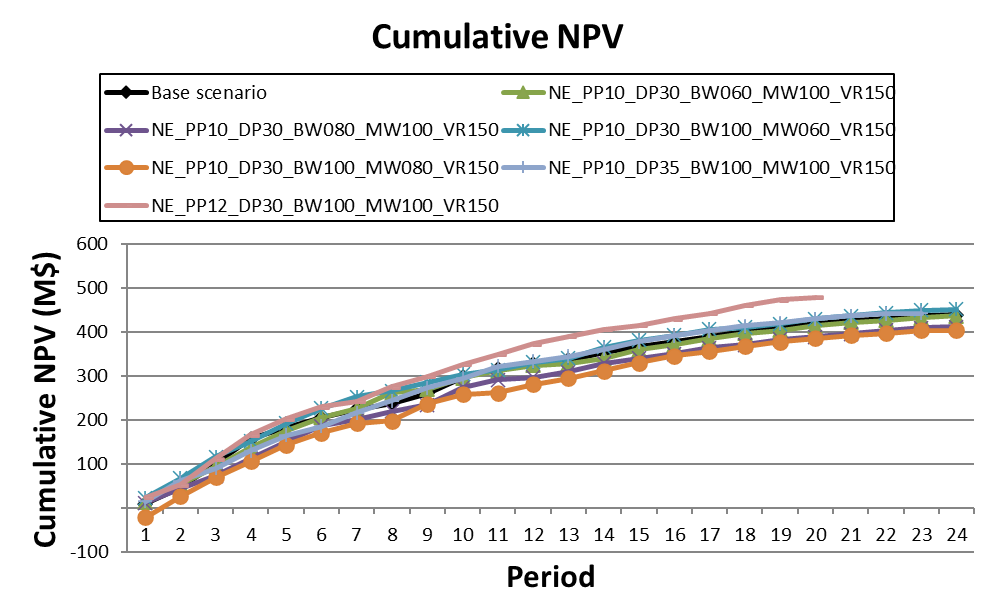

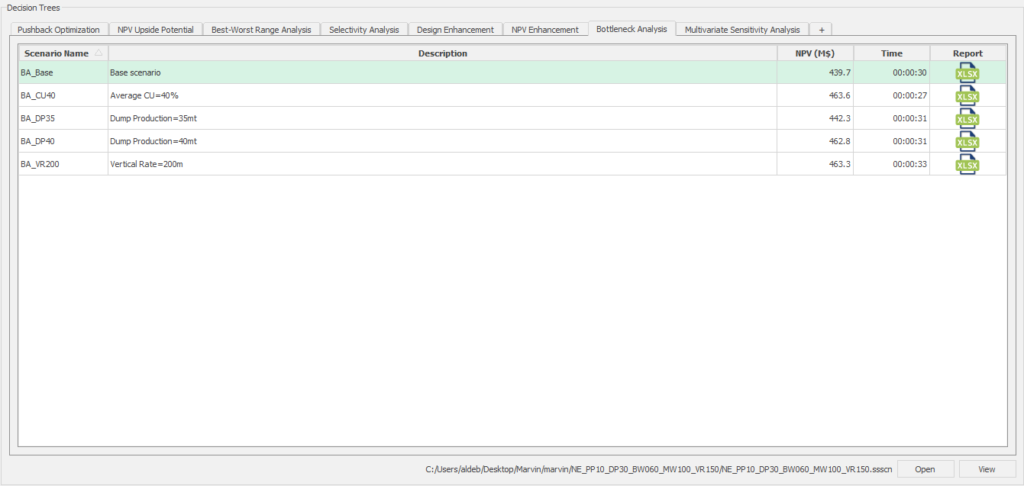

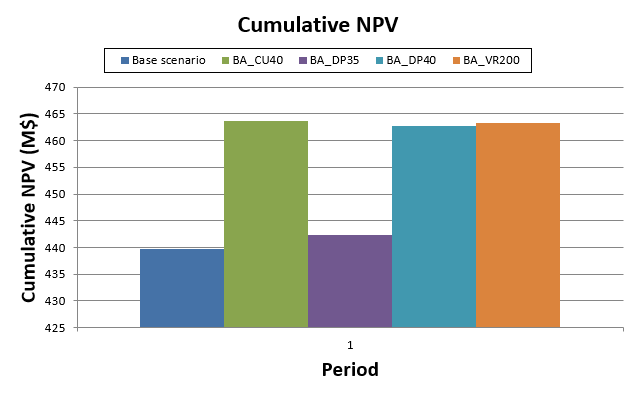

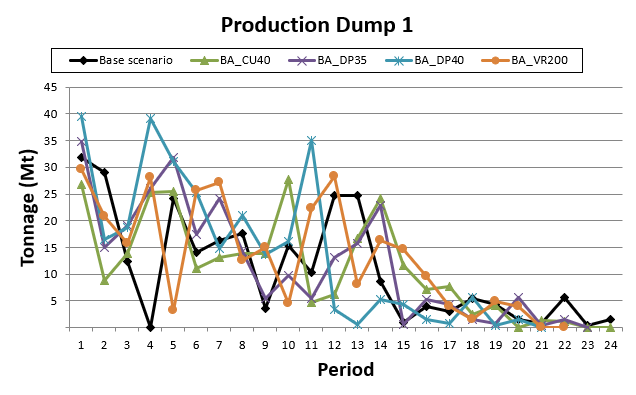

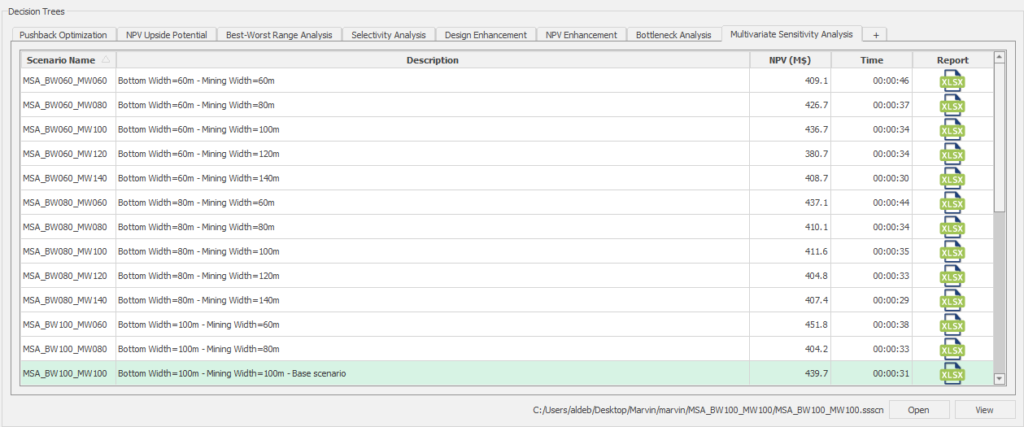

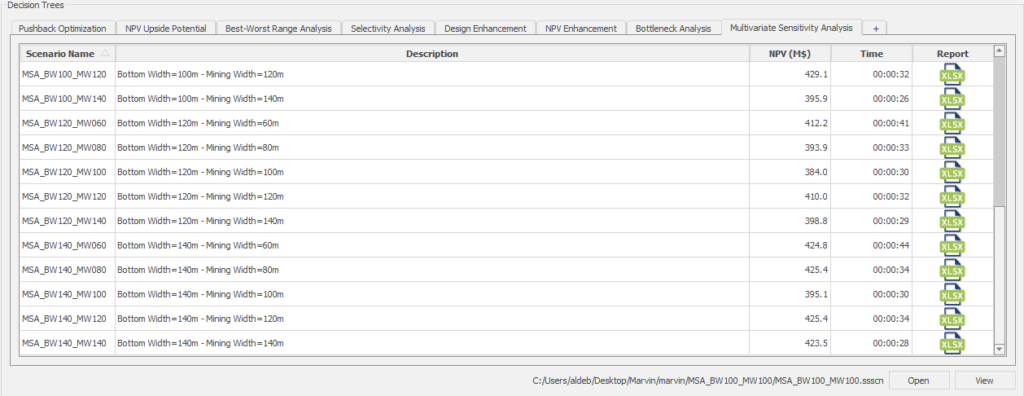

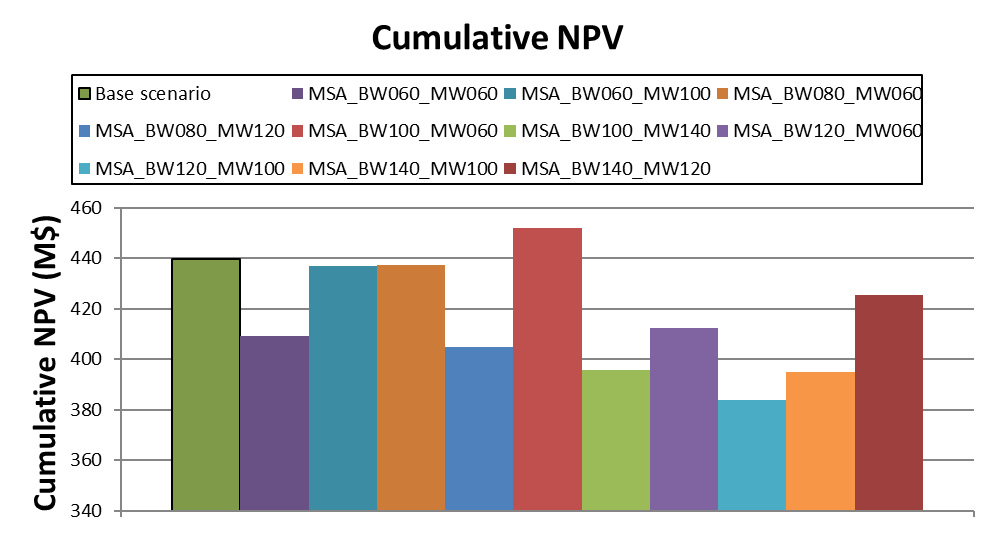

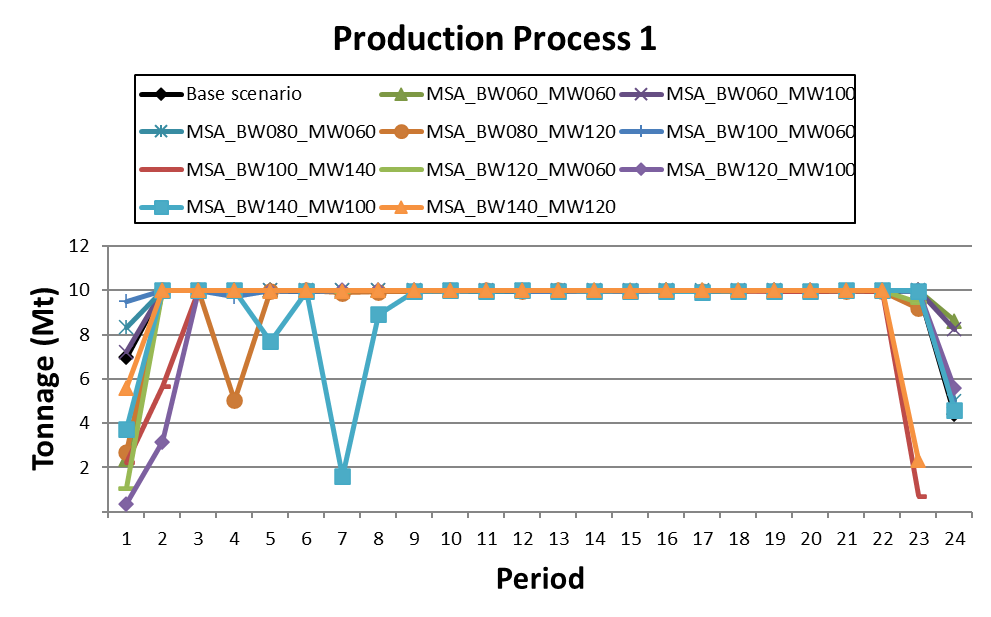

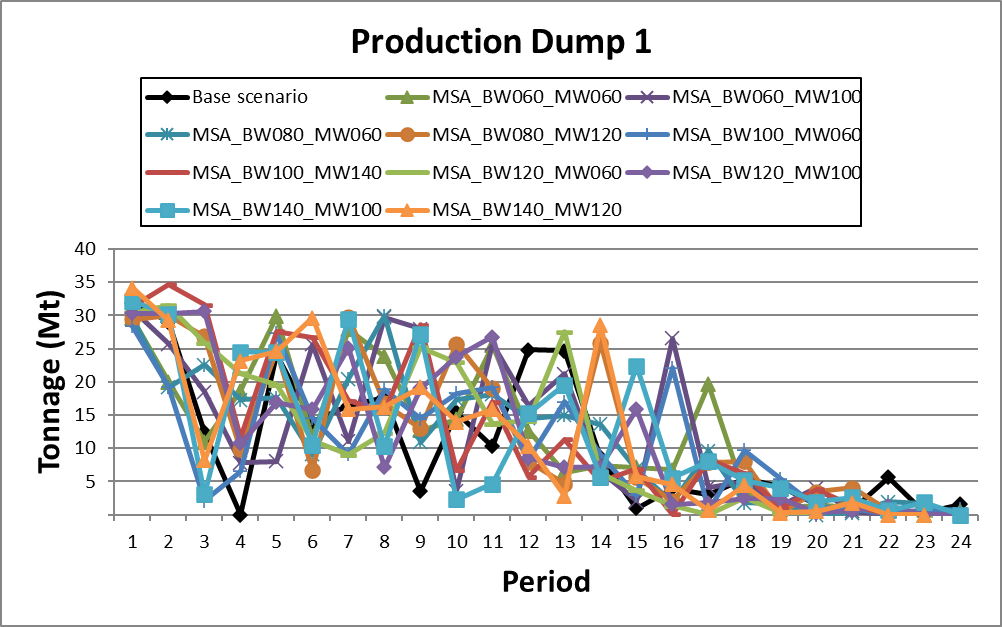

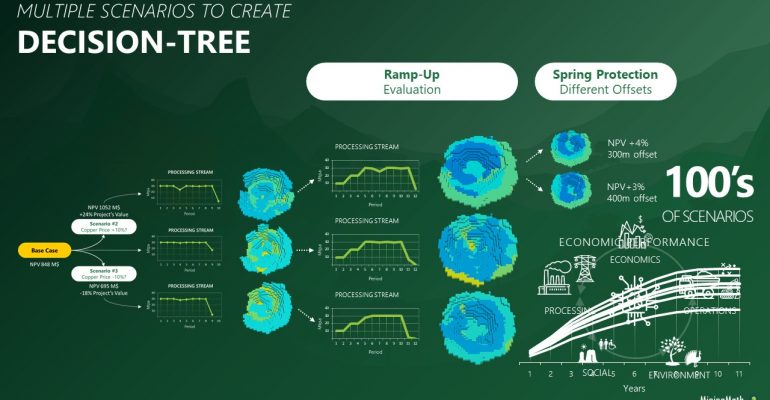

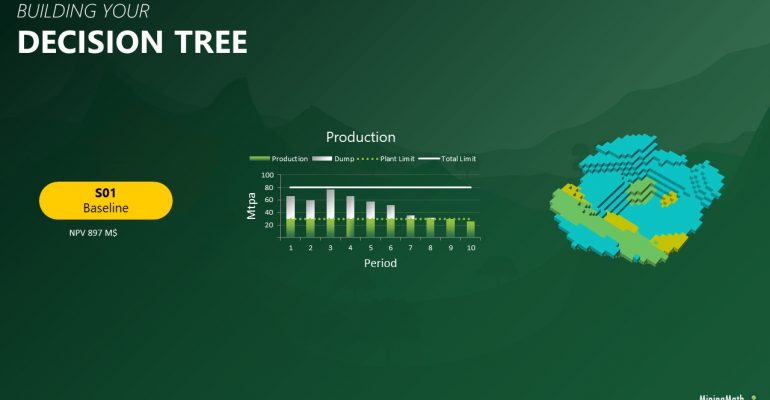

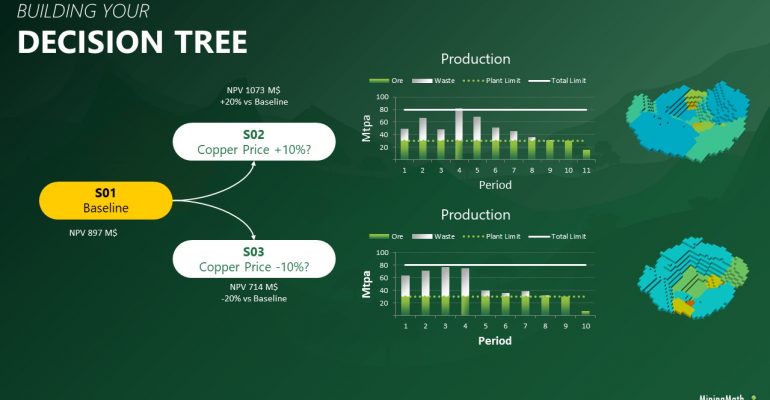

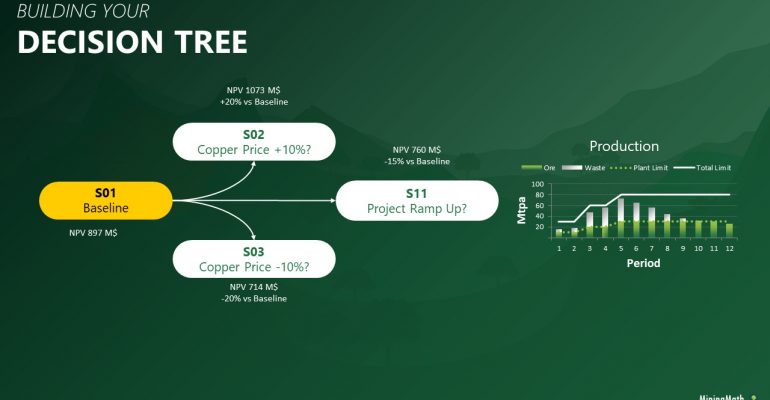

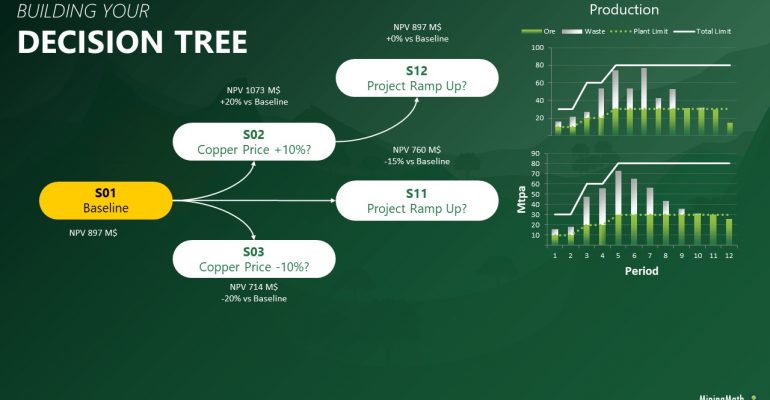

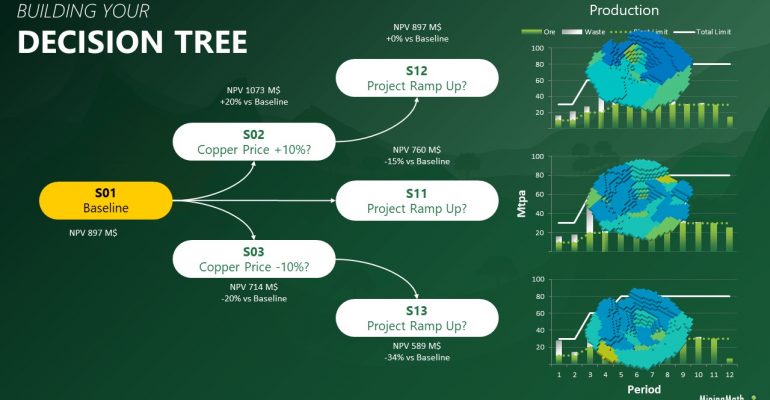

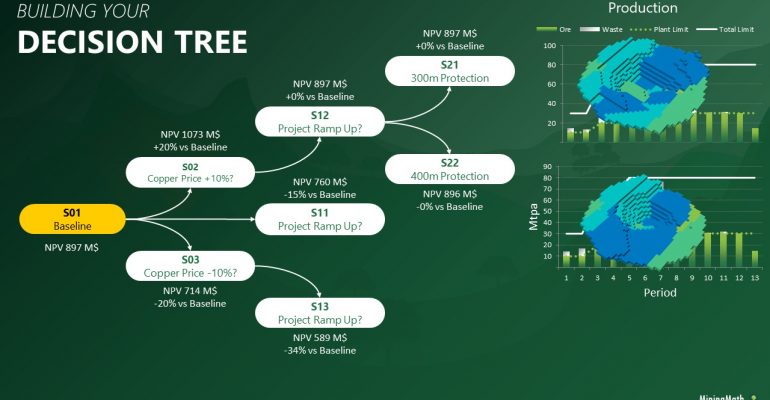

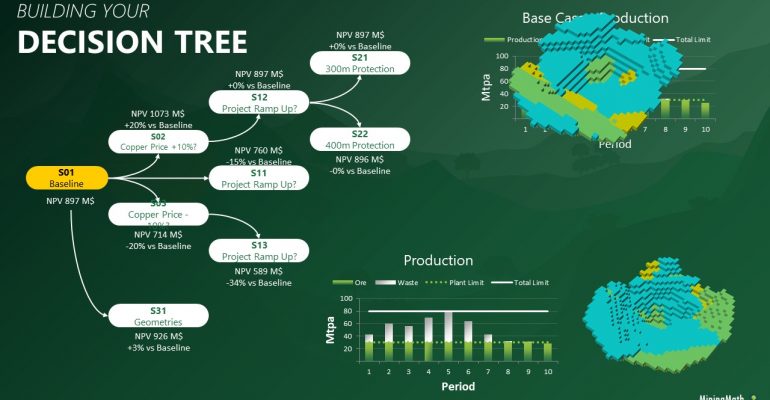

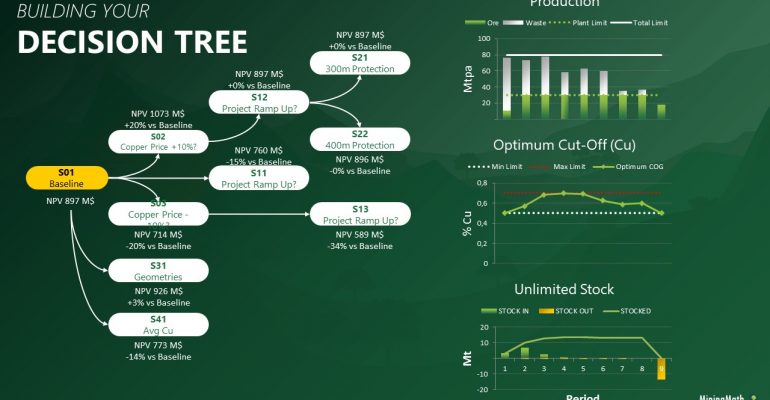

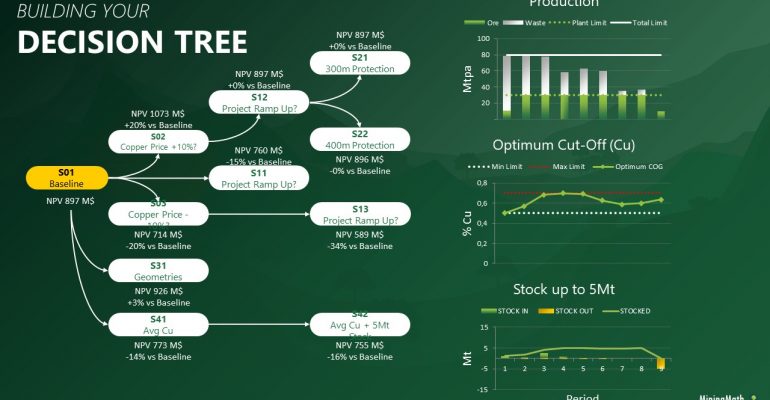

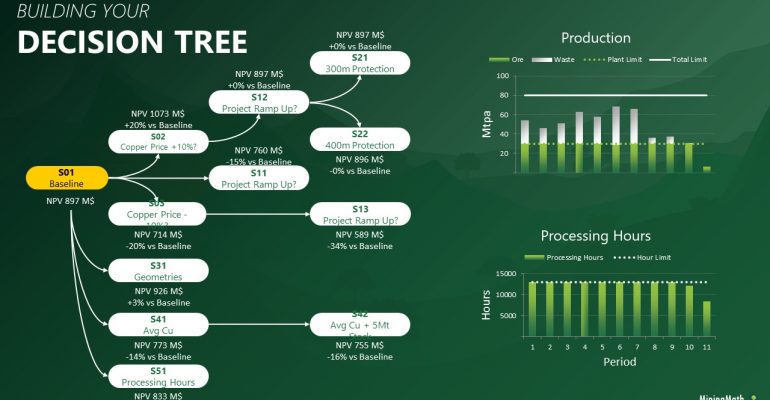

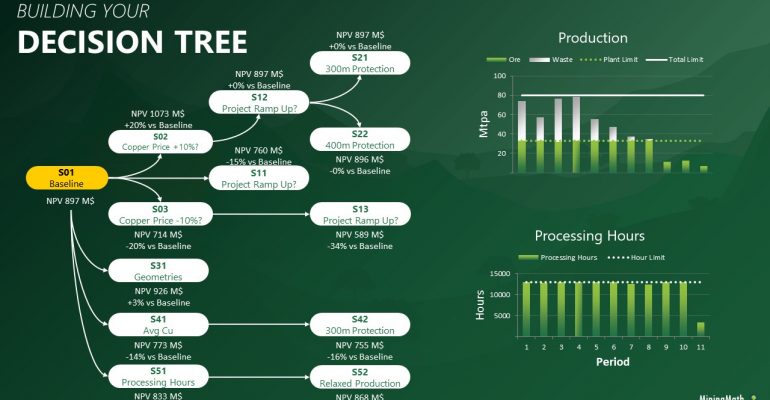

Decision Trees: Decision Trees provide you a detailed broad view of your project, allowing you to plan your mining sequence by analyzing every possibility in light of constraints applied to each scenario, which options are more viable and profitable to the global project, as well as how these factors impact the final NPV.

Understand the technology in depth

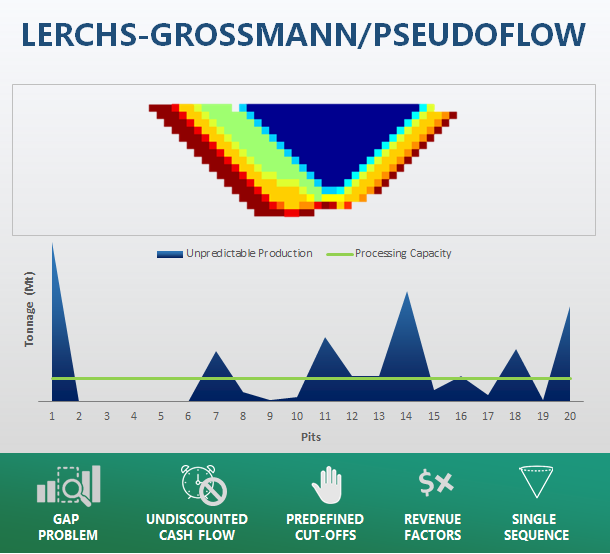

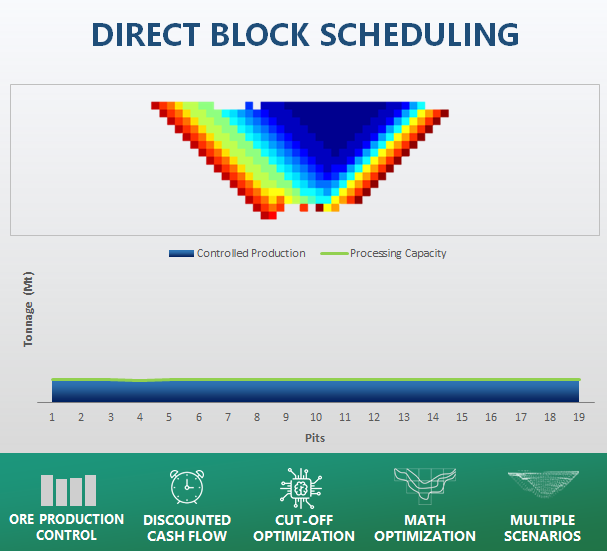

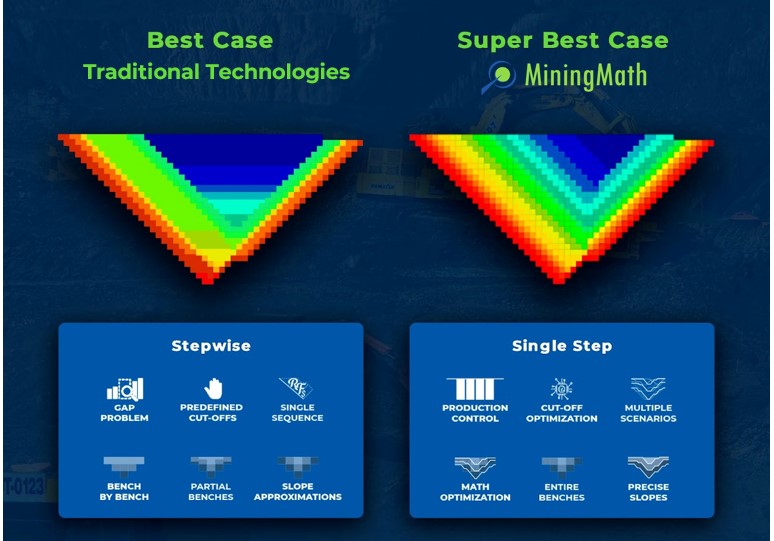

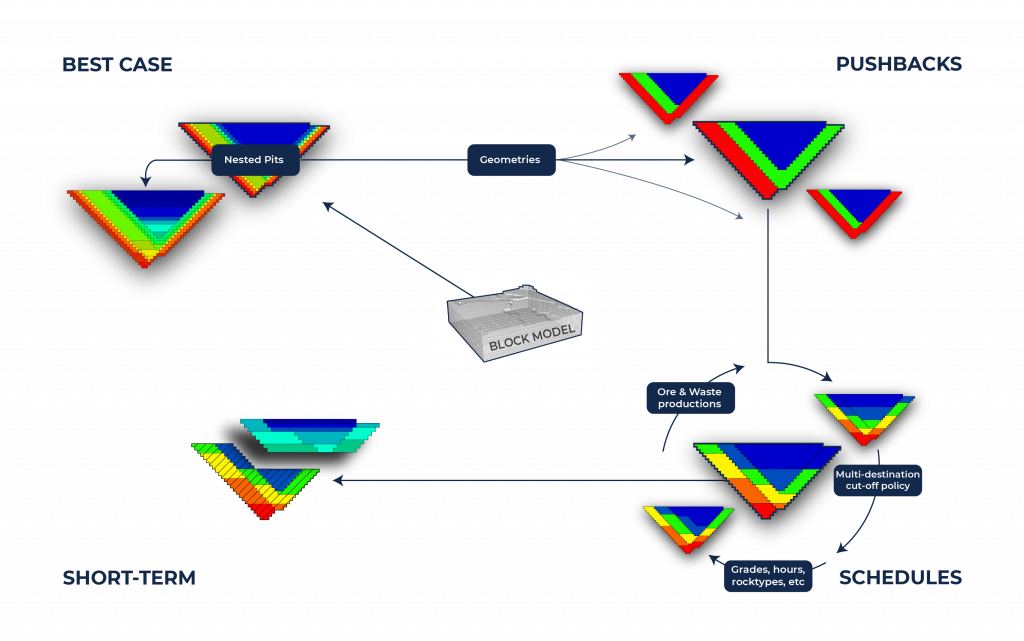

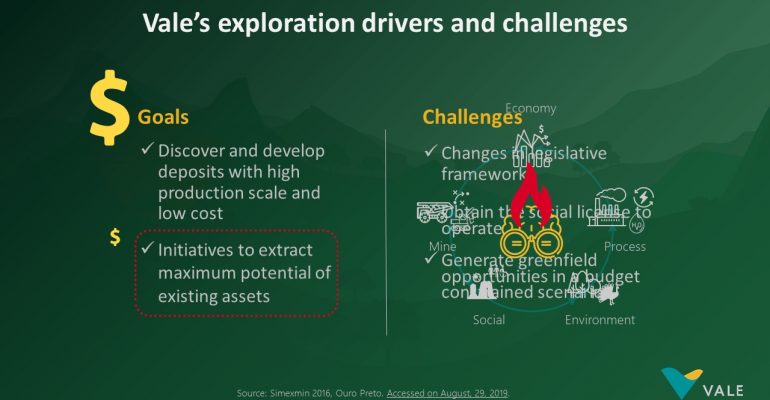

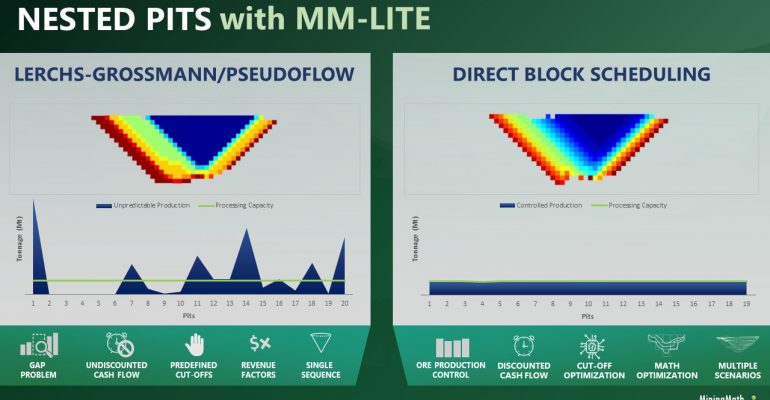

Current best practices: Here we go through the modern technology usually employed by other mining packages. It is important to understand these in order to comprehend MiningMath differentials.

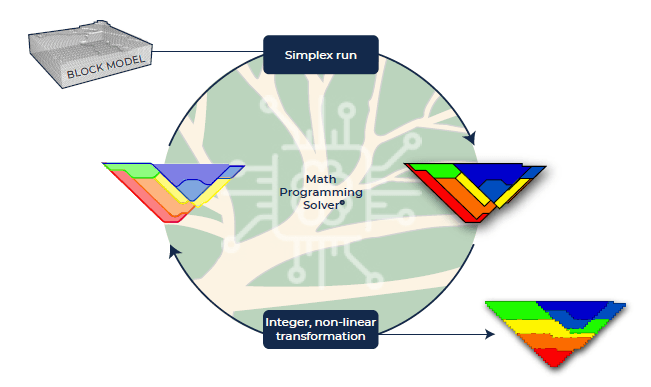

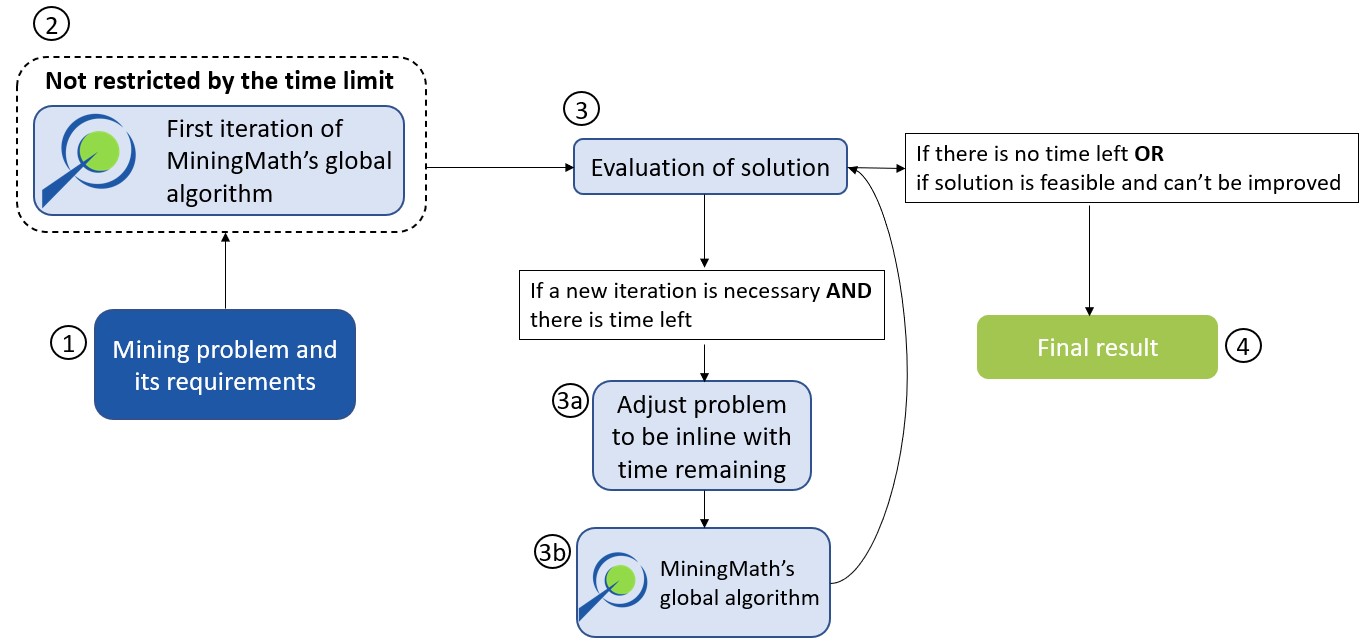

MiningMath uniqueness: Now that you’ve practiced the basics of MiningMath, and understand how other mining packages work, it’s time to get deep into the theory behind the MiningMath technology.

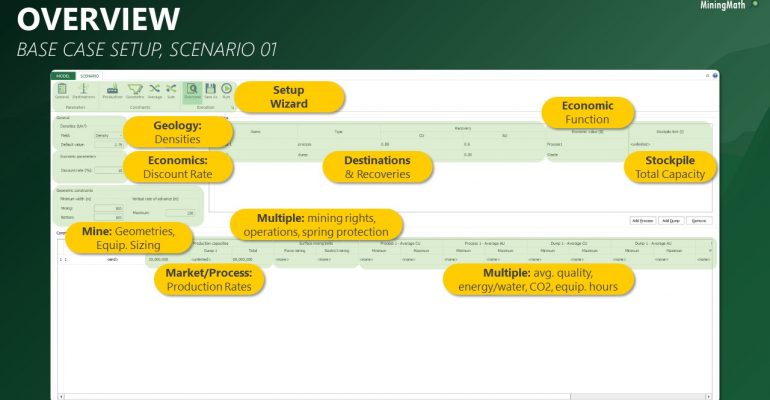

Interface Overview: It’s time understand our interface overview with detailed information about every screen and constraints available in MiningMath. Home page, Model tab, Scenario tab, and Viewer for a better understanding of the possibilities.

Using and validating your data

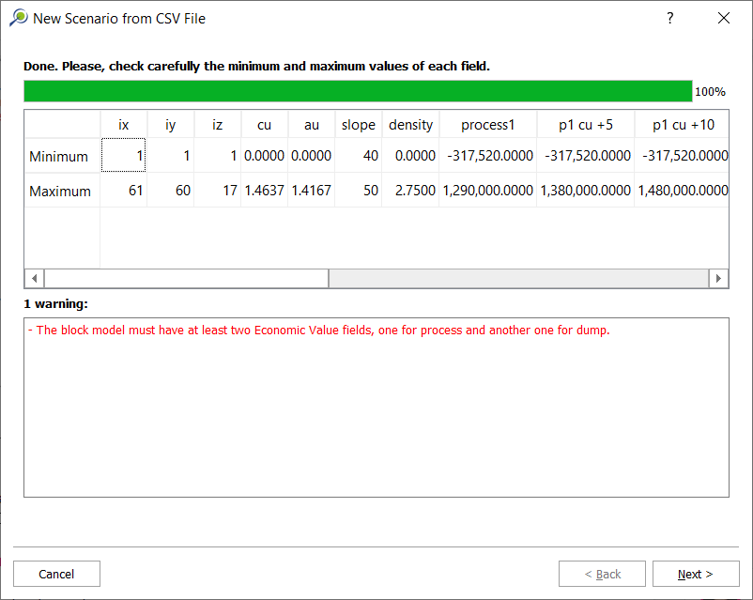

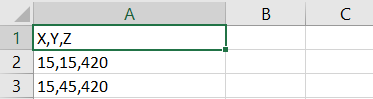

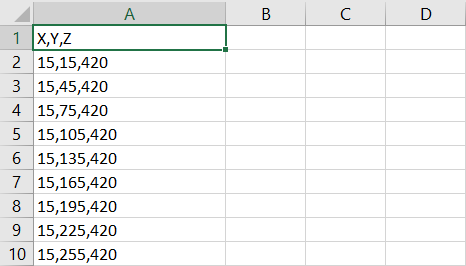

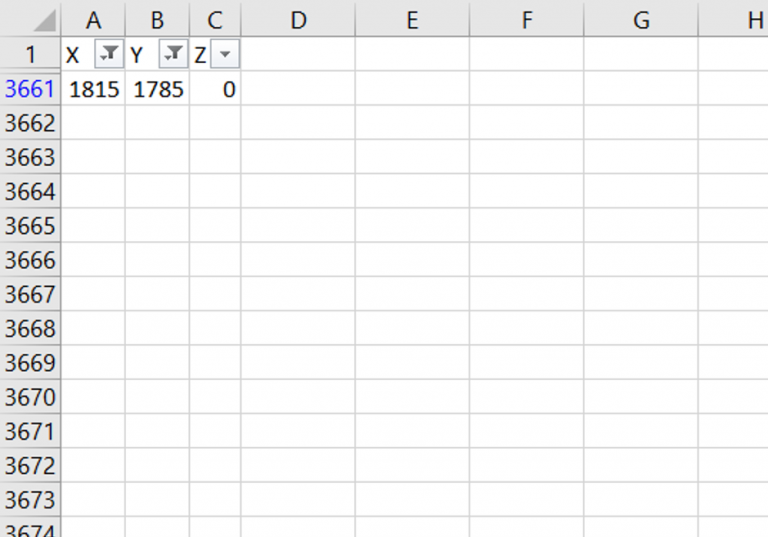

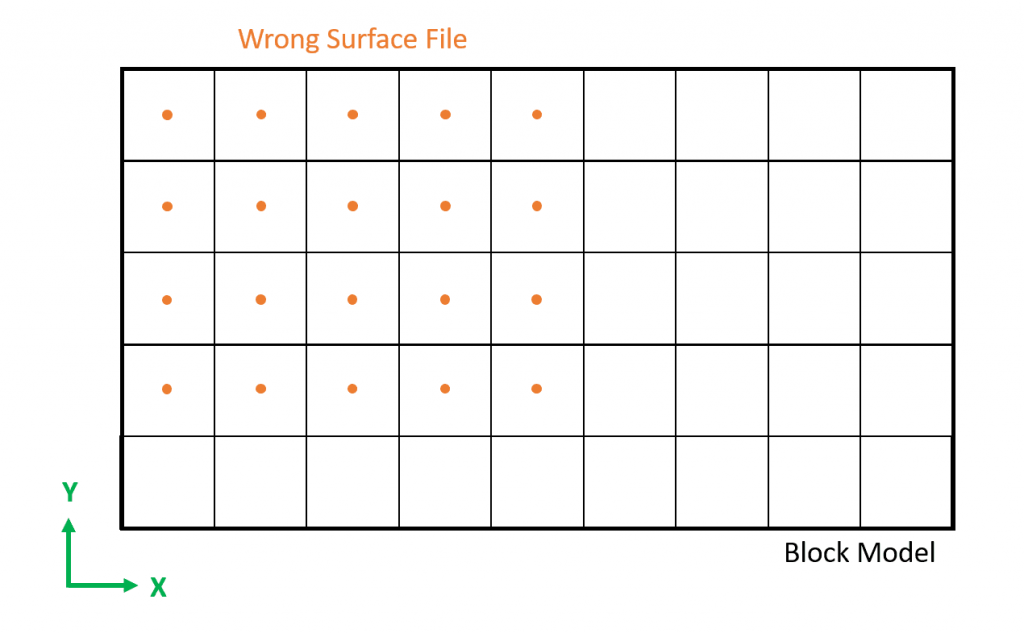

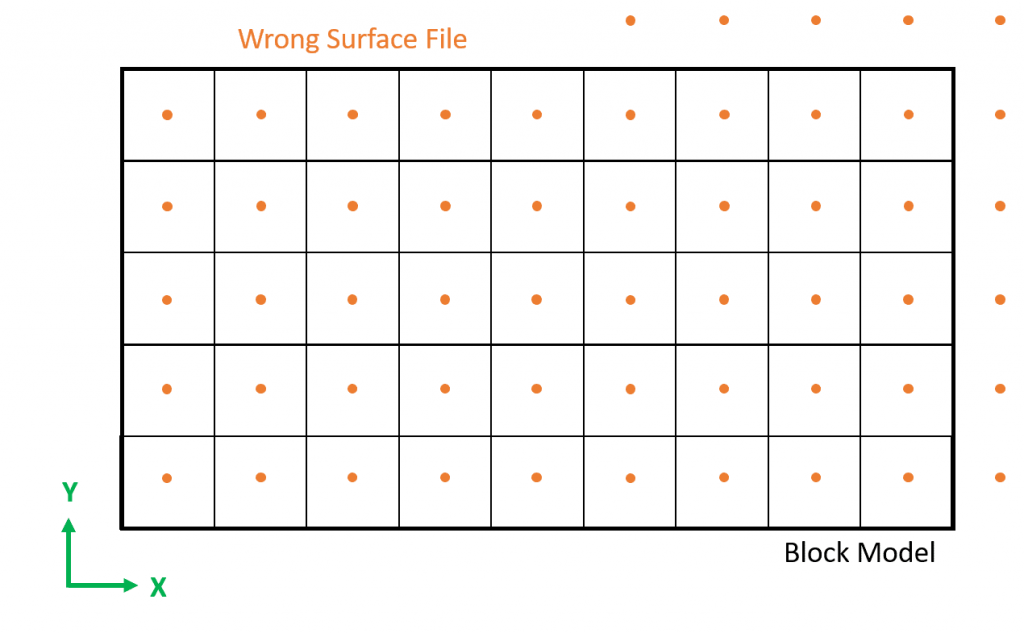

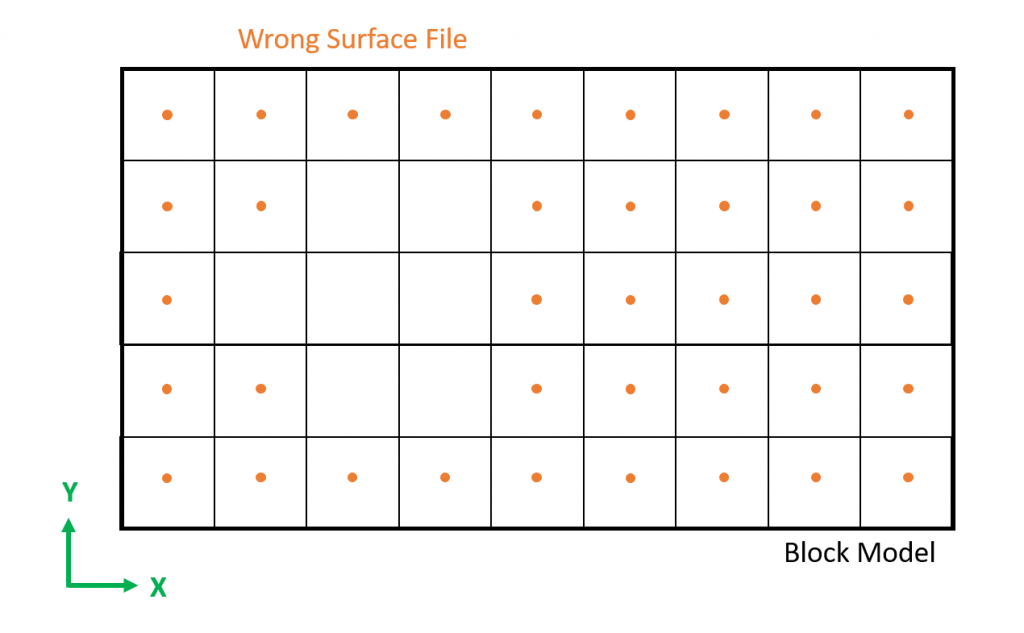

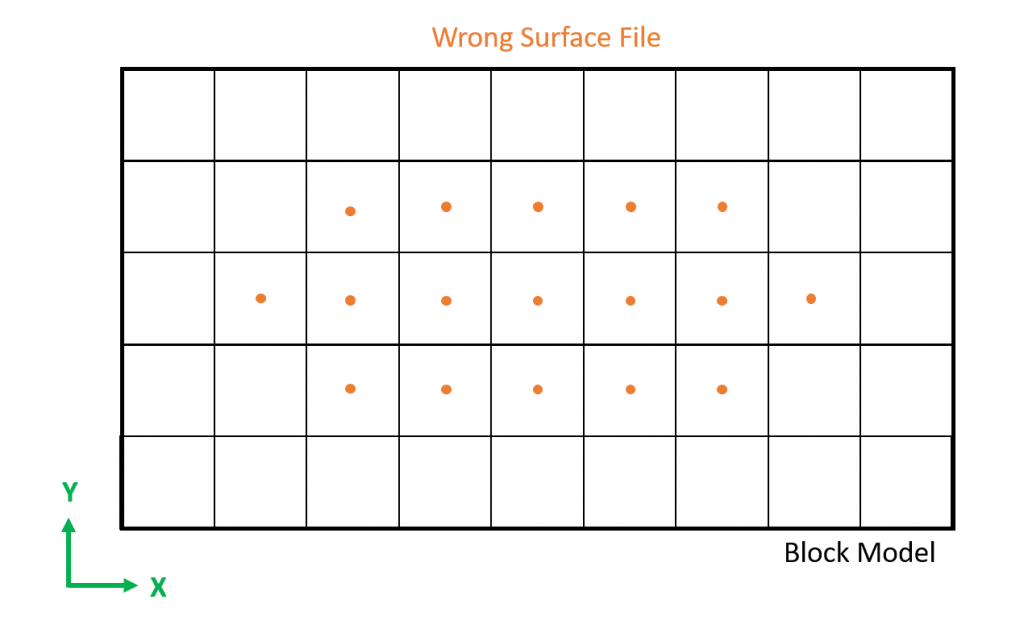

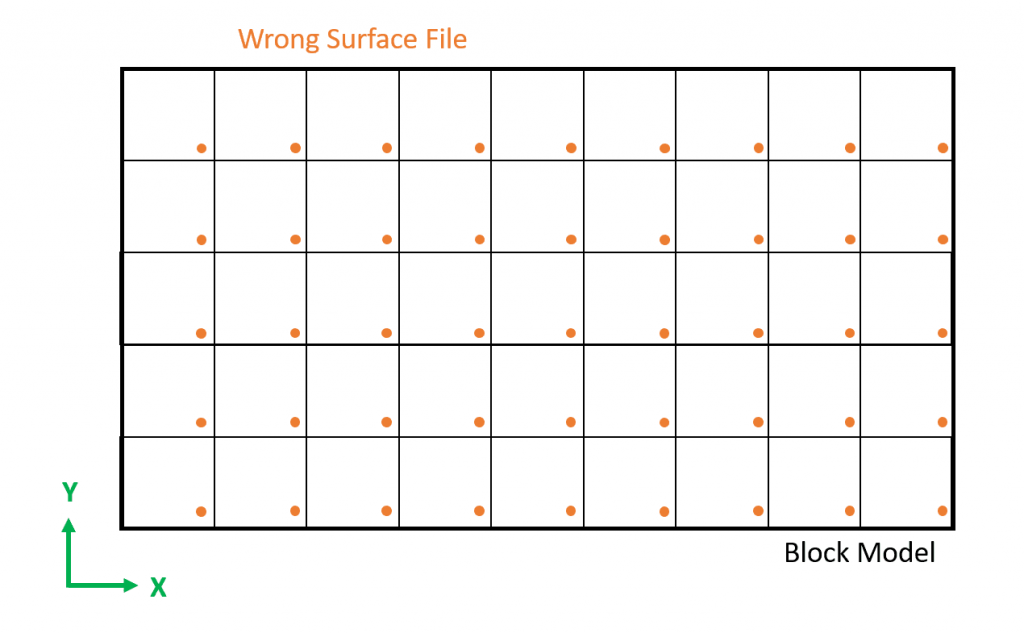

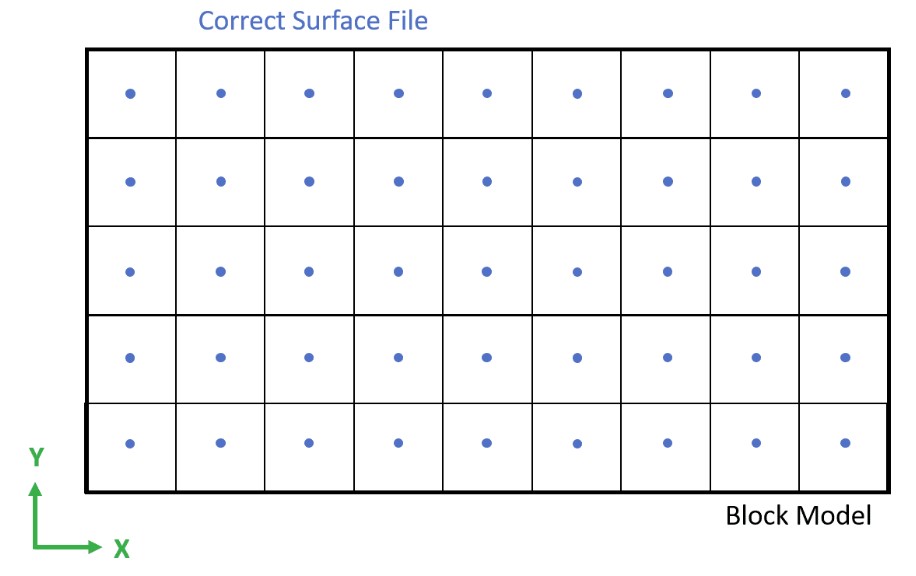

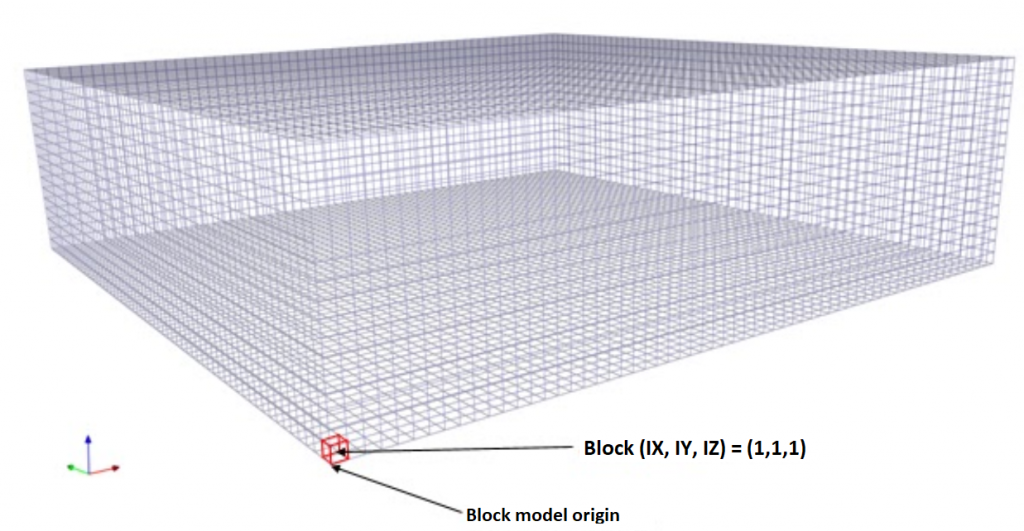

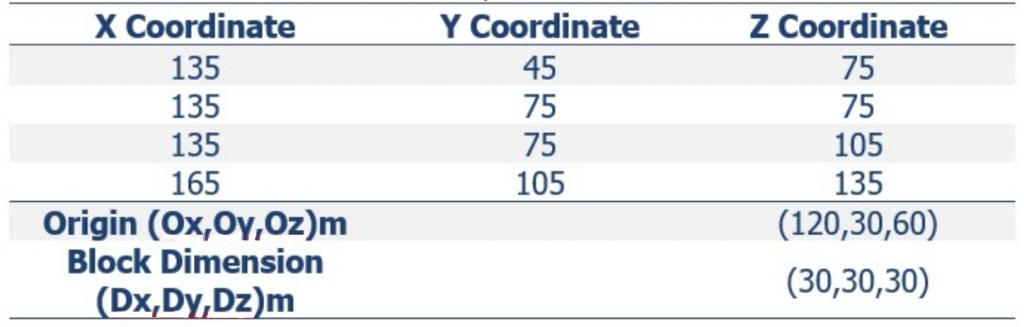

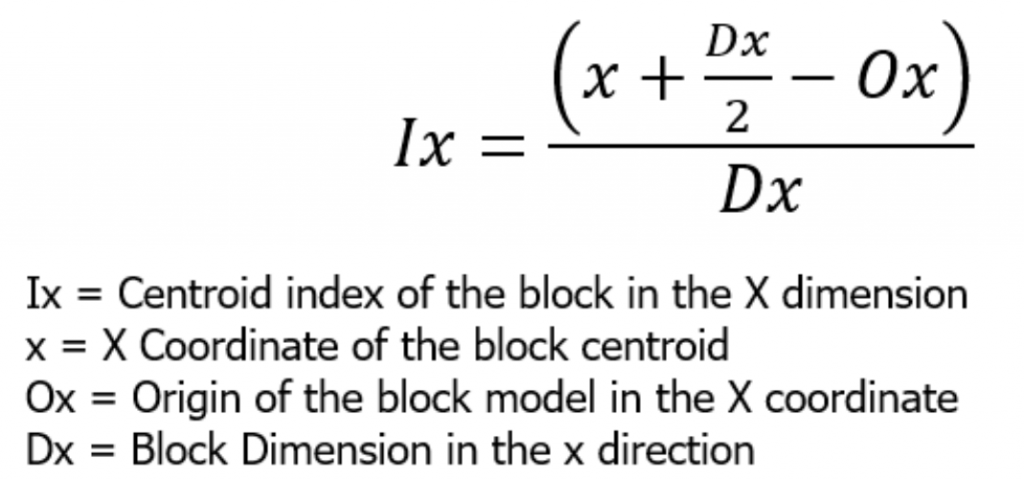

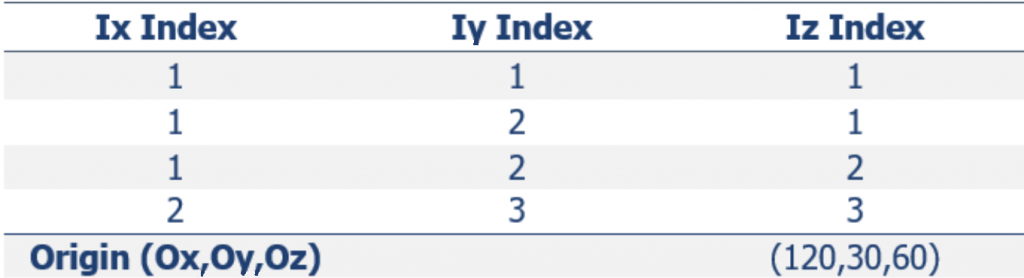

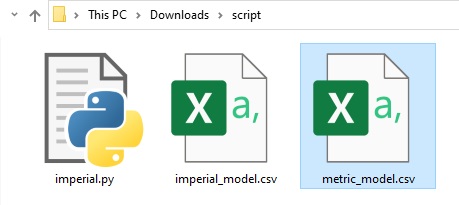

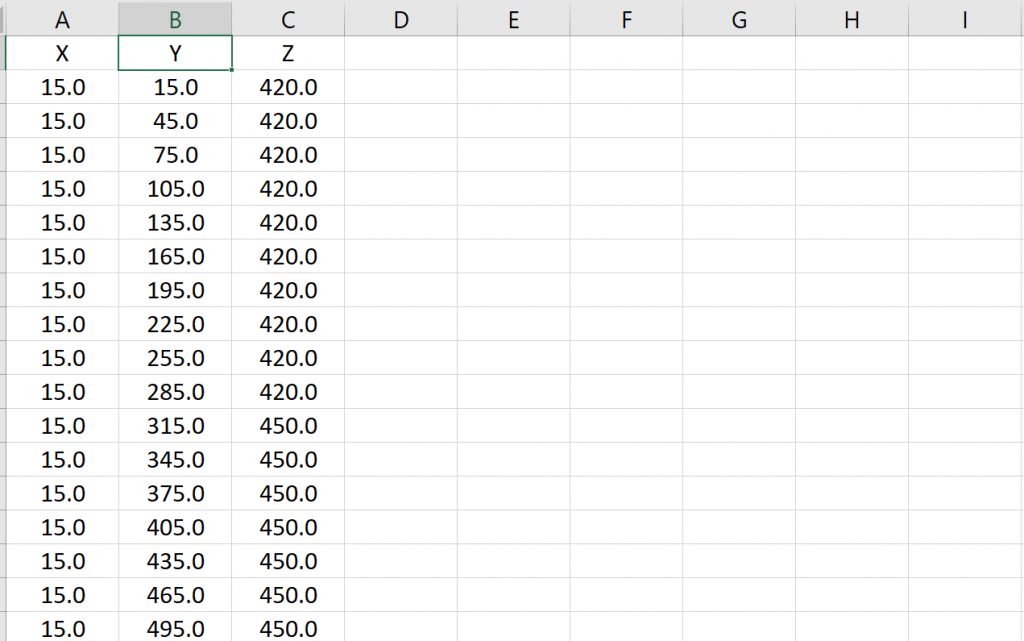

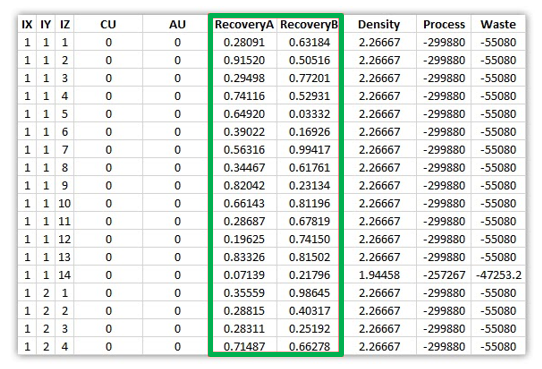

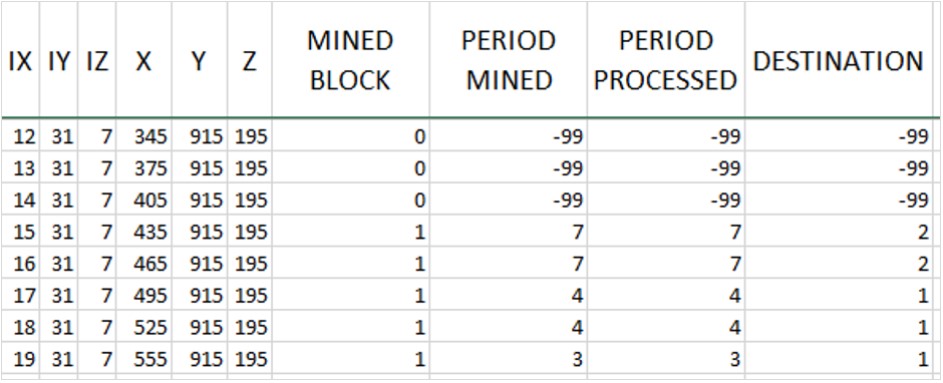

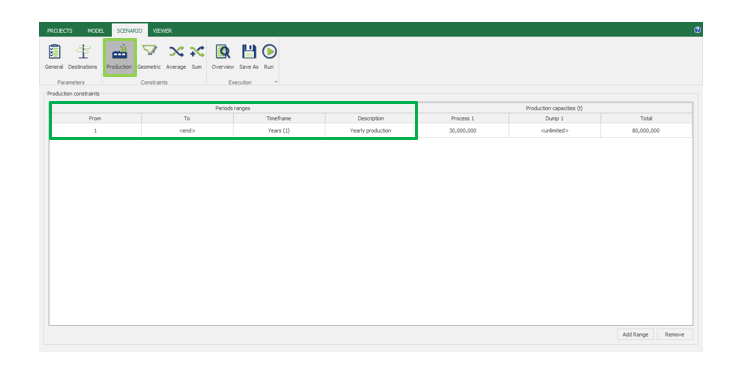

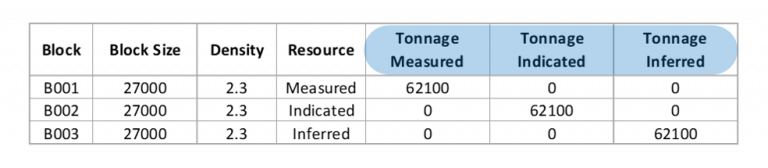

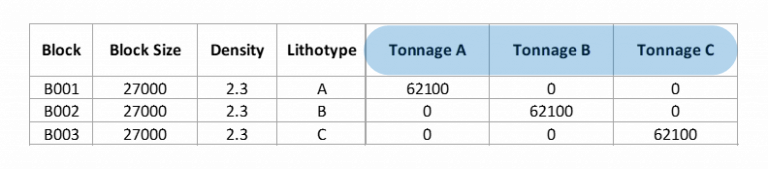

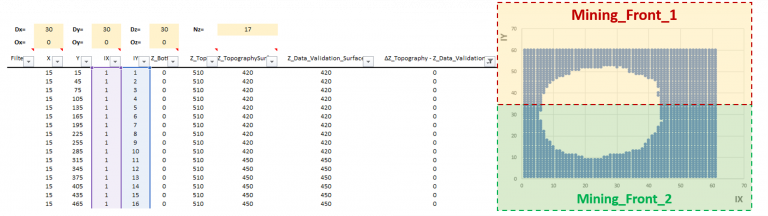

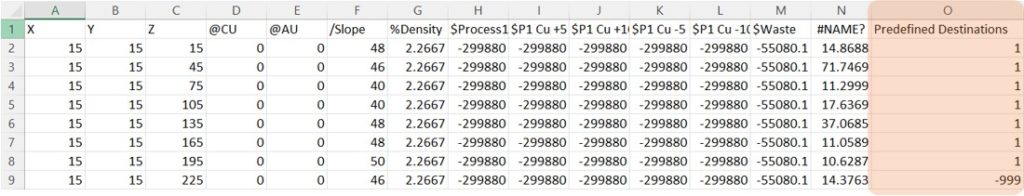

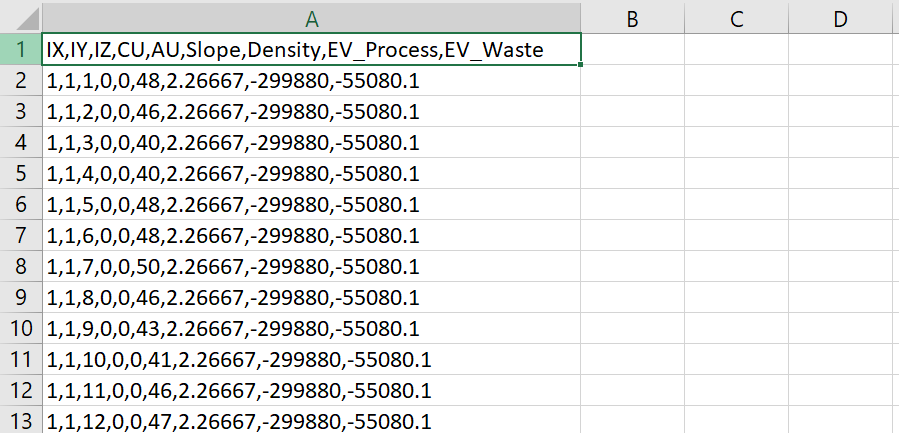

Formatting the Block Model: Learn how to format your block model data and use it in MiningMath.

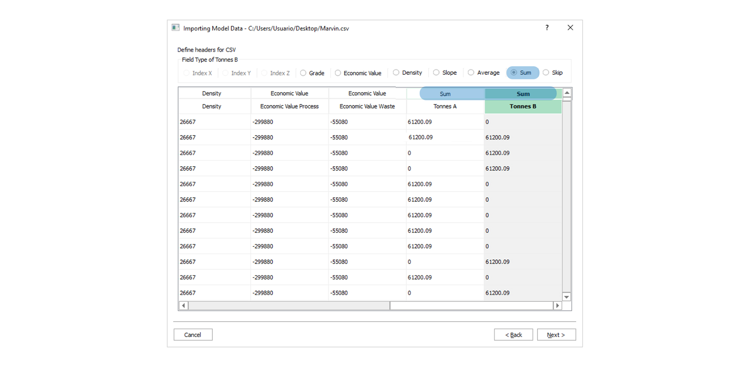

Importing the block model: Go through the importation process and to proper configure your data.

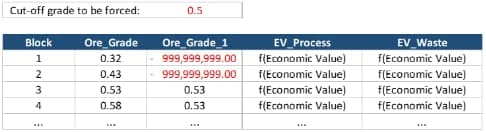

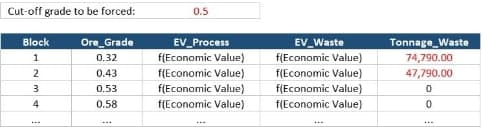

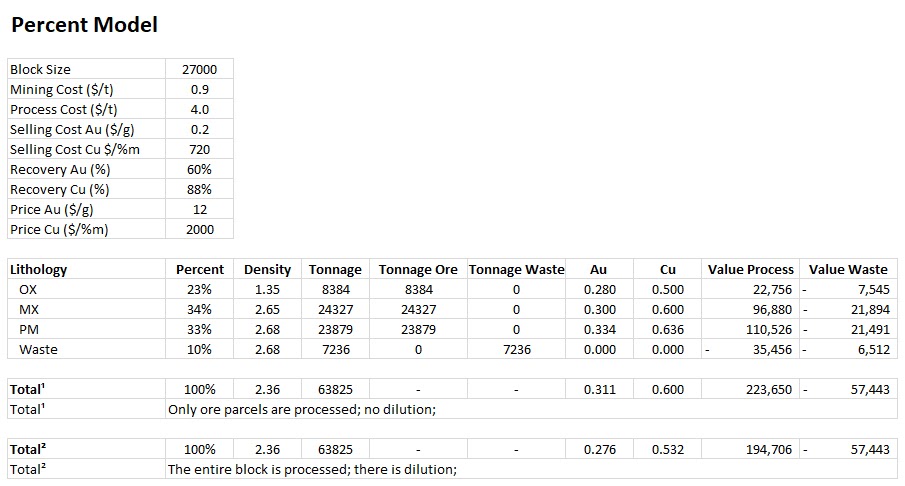

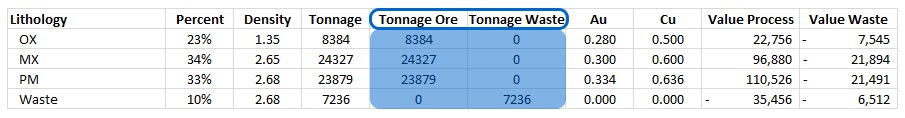

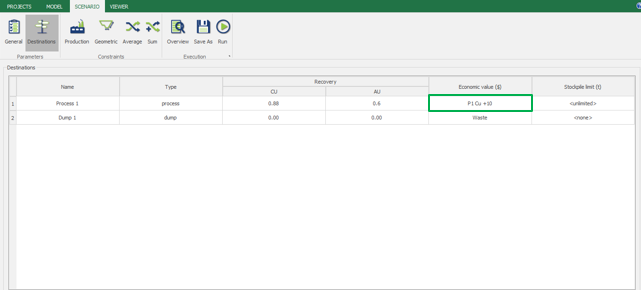

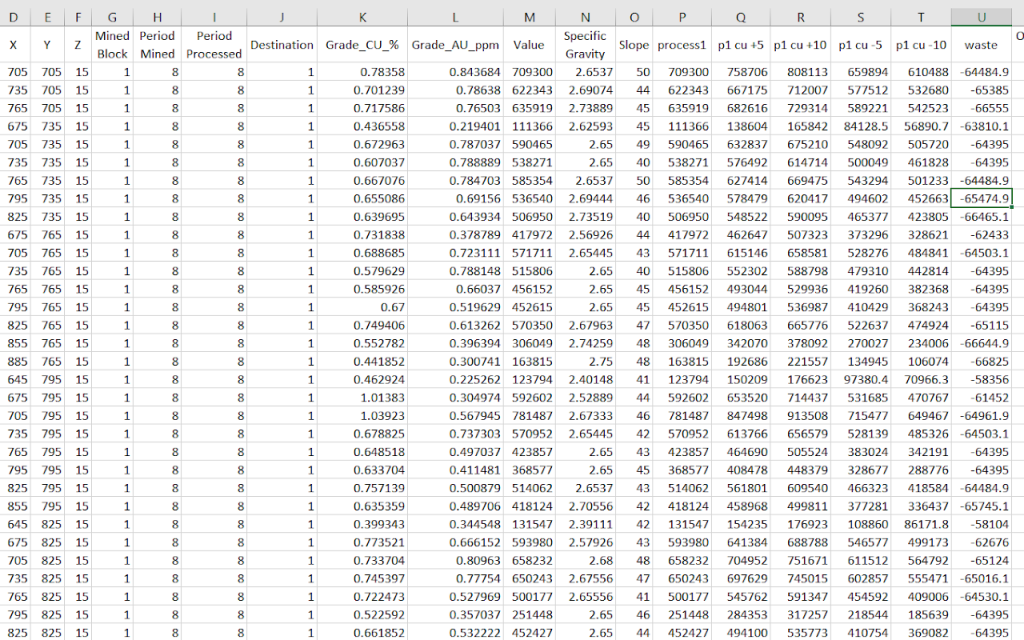

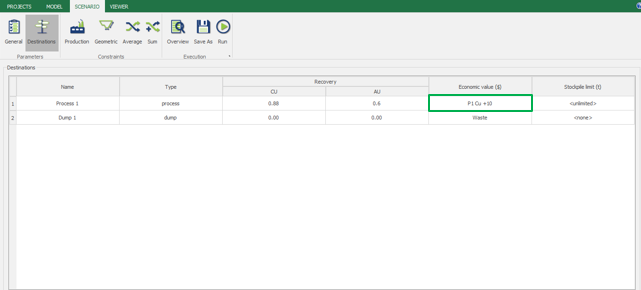

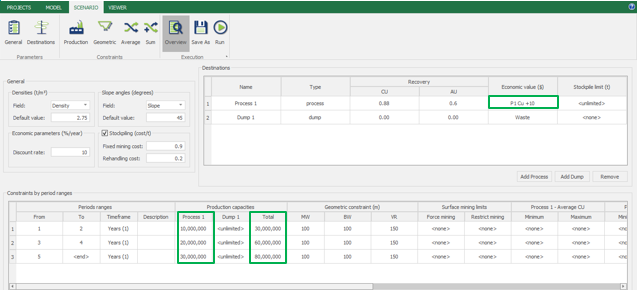

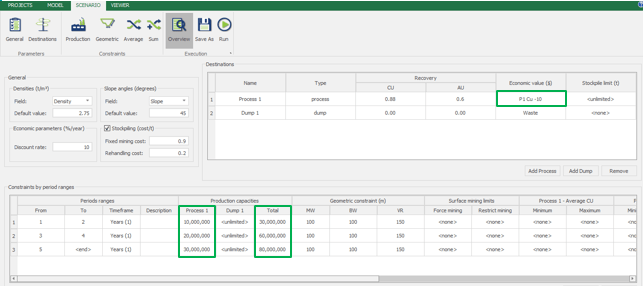

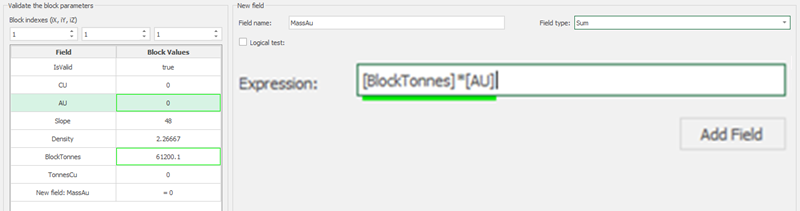

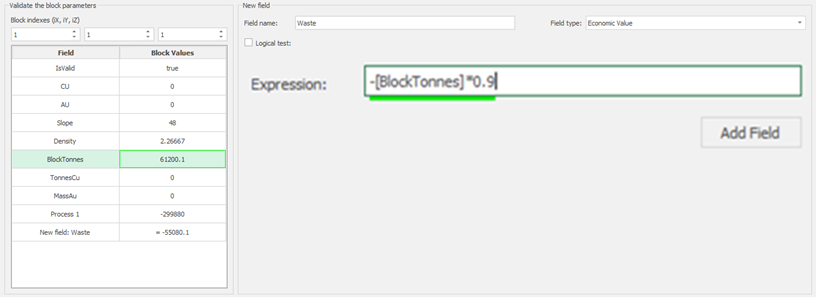

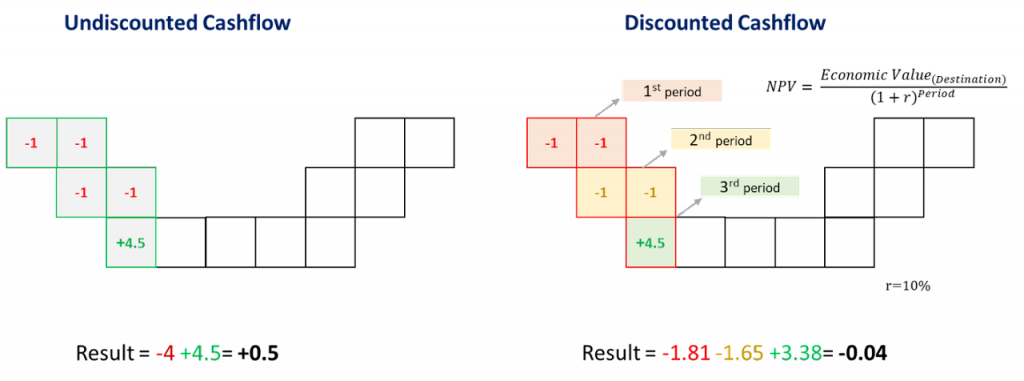

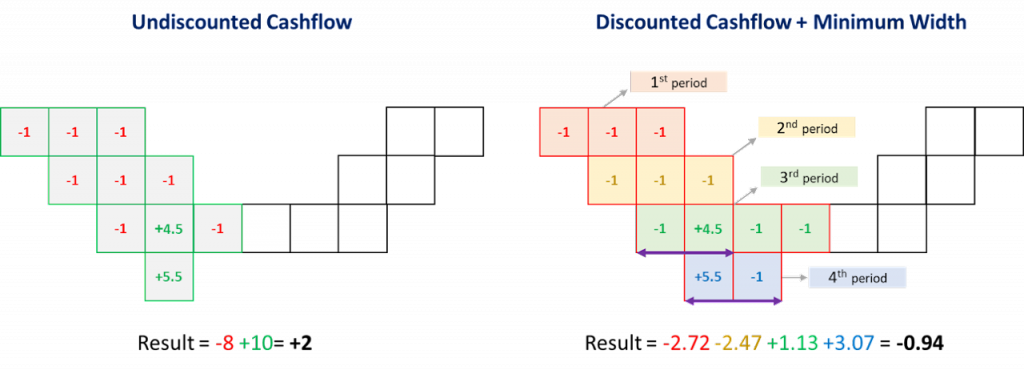

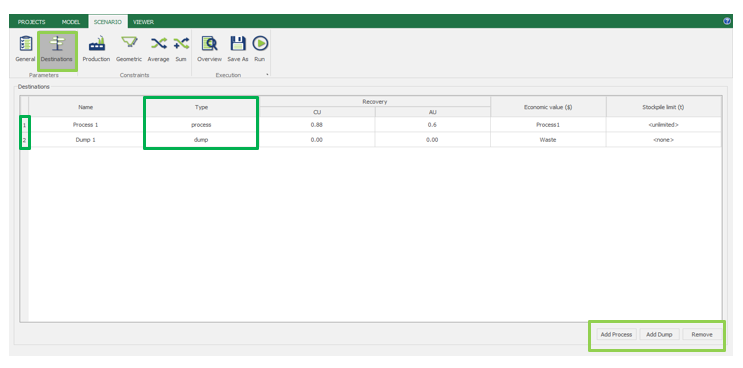

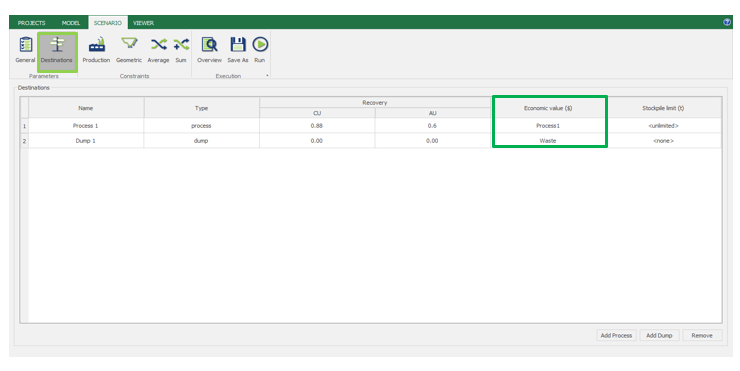

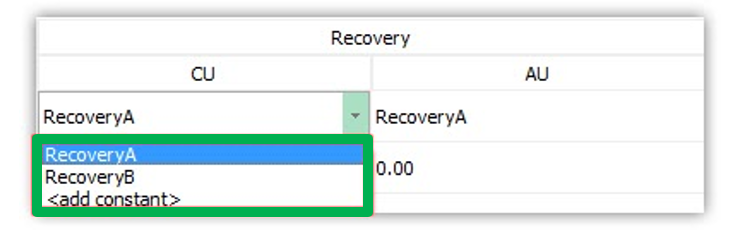

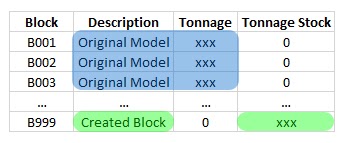

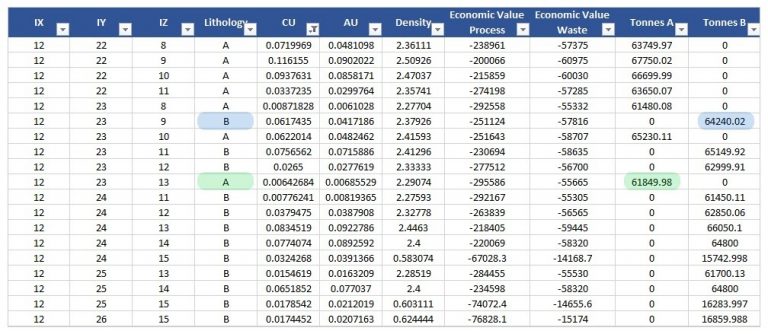

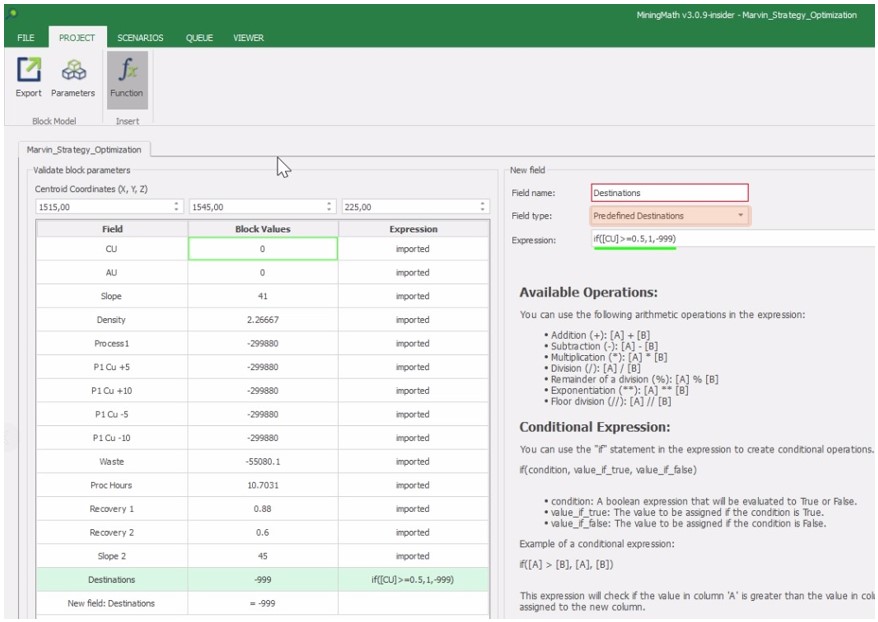

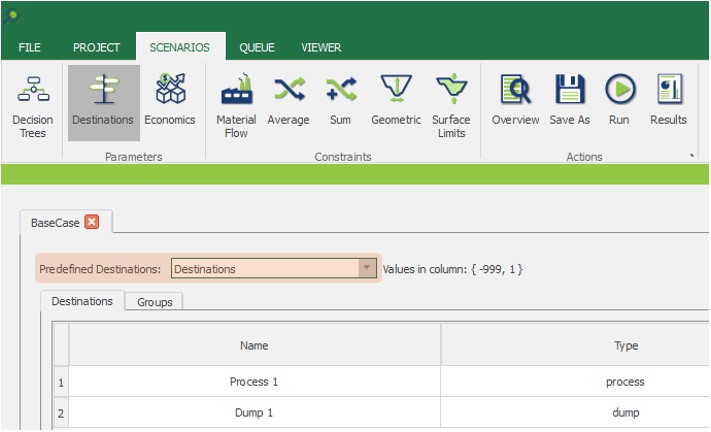

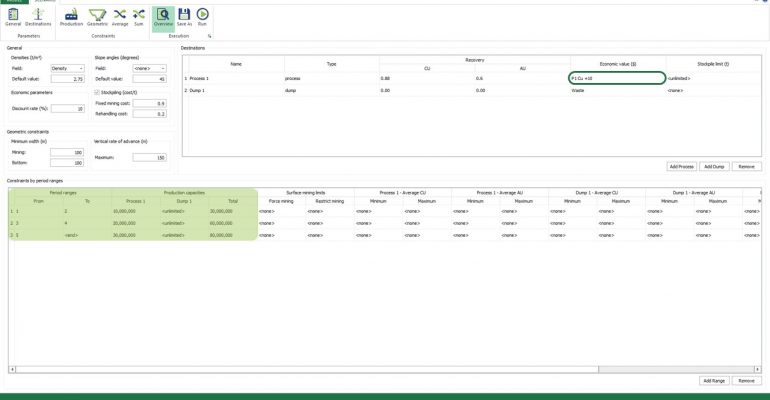

Economic Values: MiningMath does not require pre-defined destinations ruled by an arbitrary cut-off grade. Instead, the software uses an Economic Value for each possible destination and for each block. After your data is formatted and imported into MiningMath, you may build your Economic Value for each possible destination.

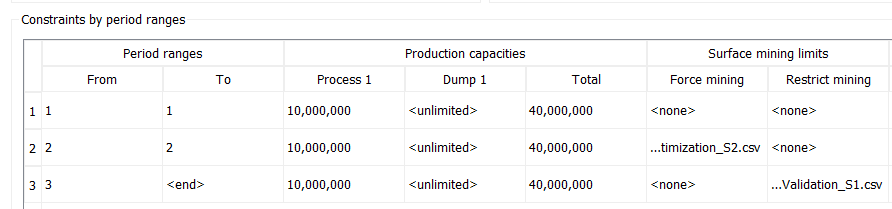

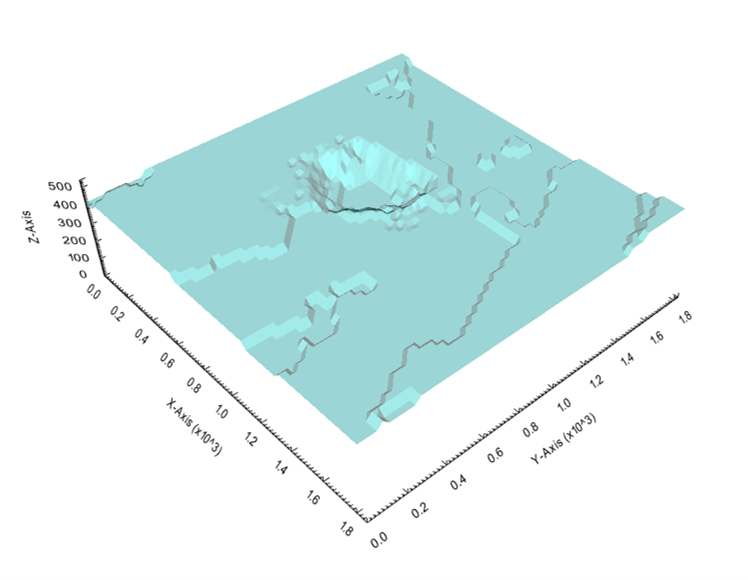

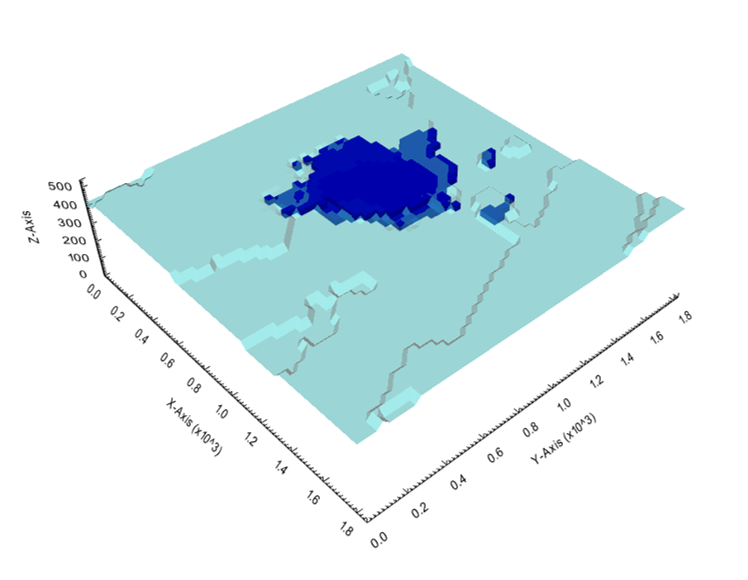

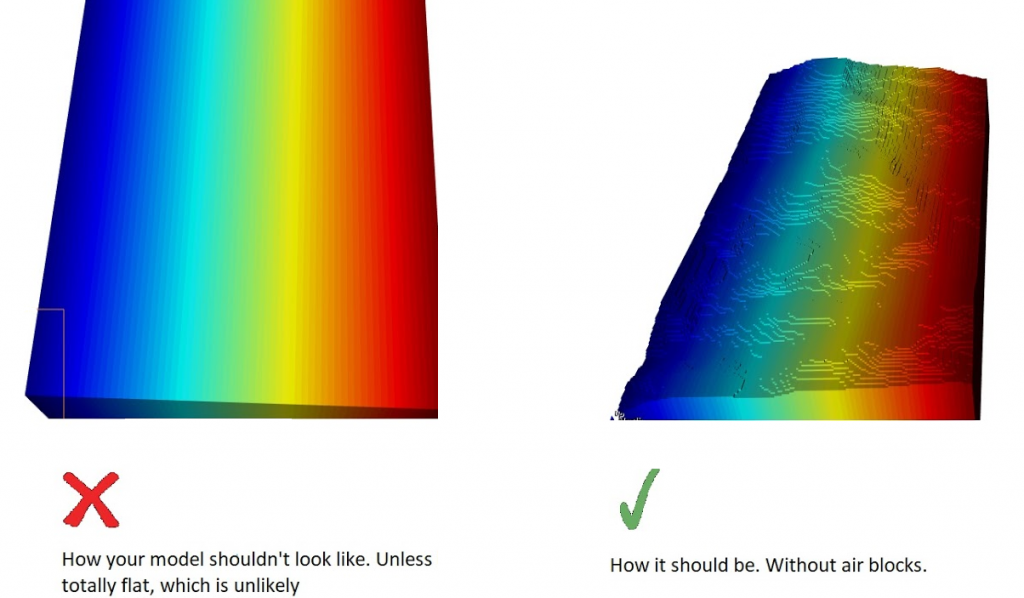

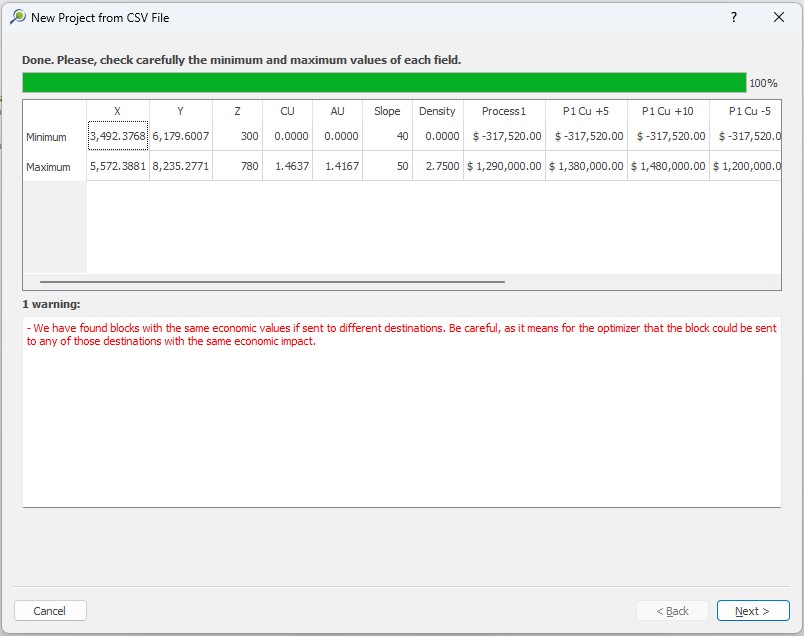

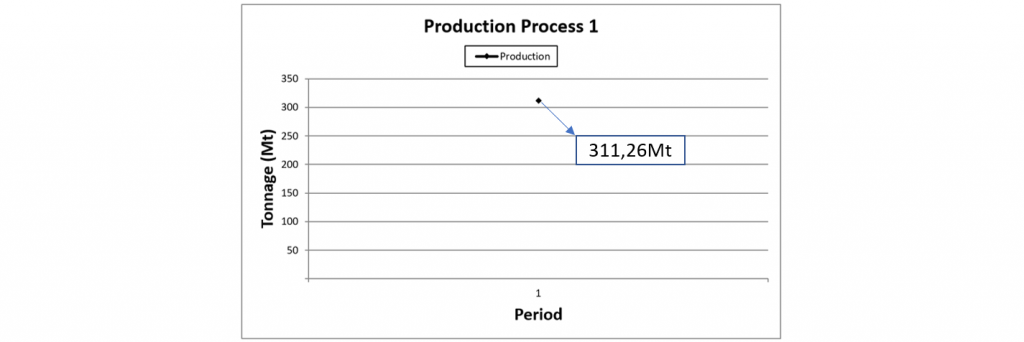

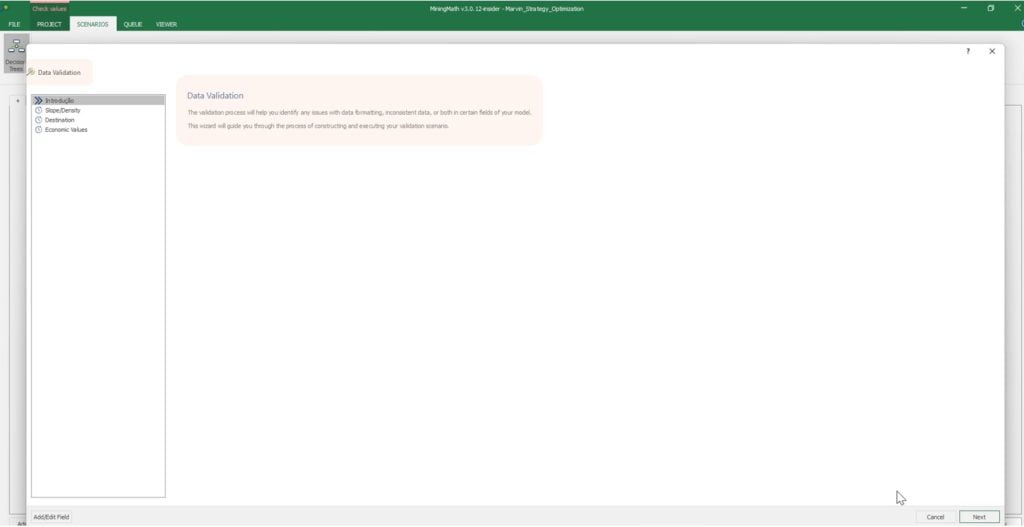

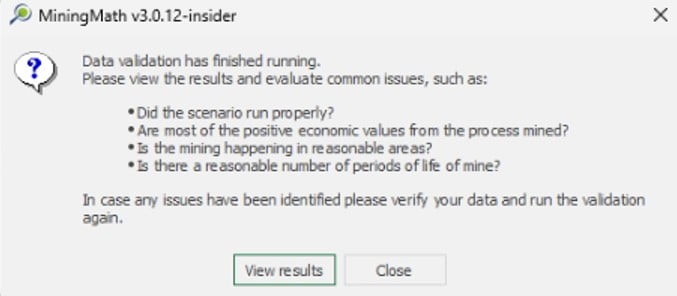

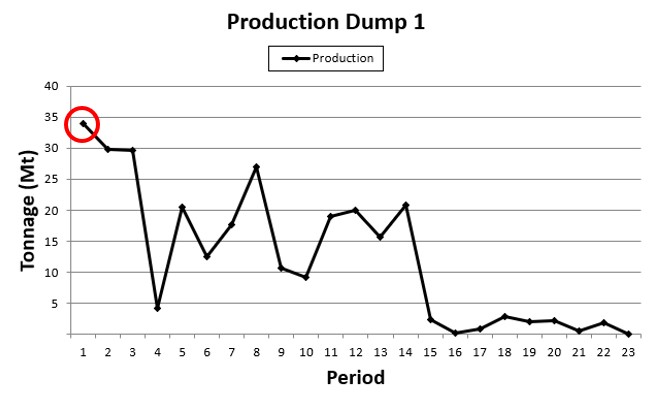

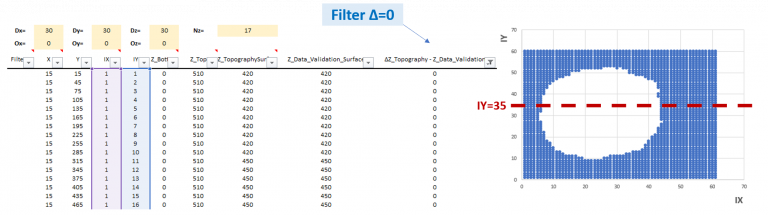

Data Validation: Once your data is set, it’s time to validate it by running MiningMath with a bigger production capacity than the expected reserves. Thus, you will get and analyze results faster.

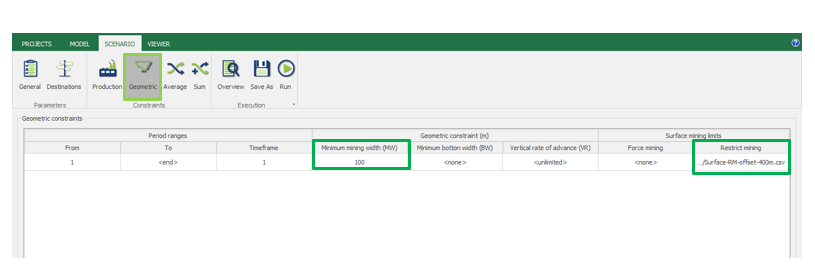

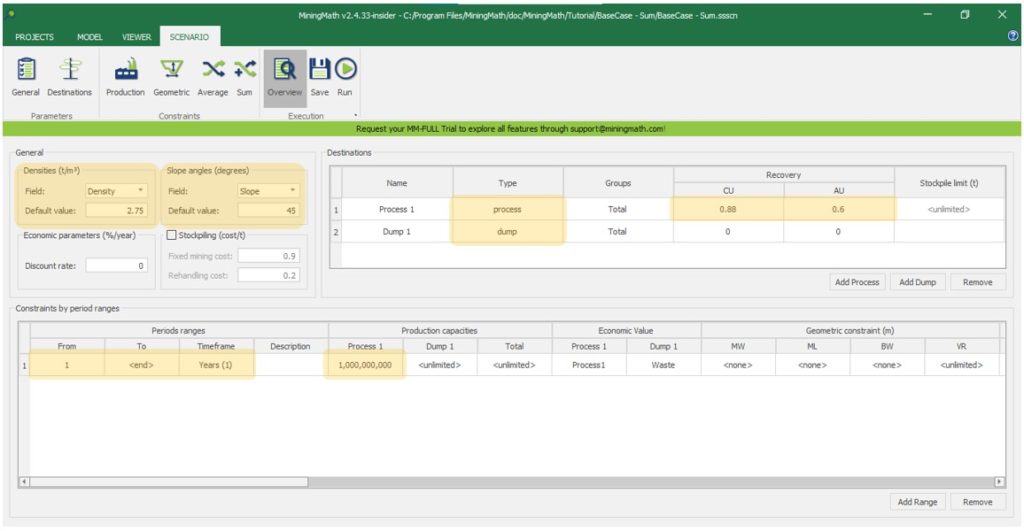

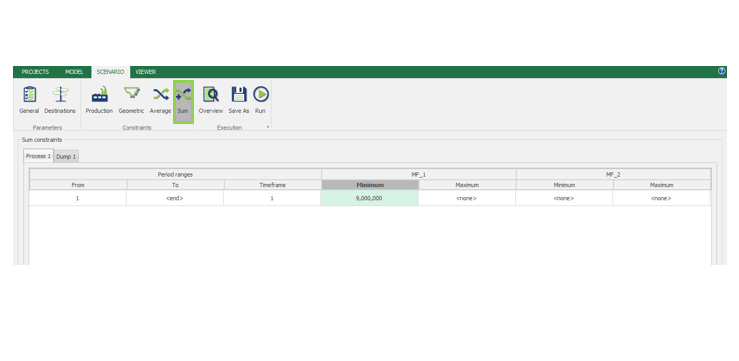

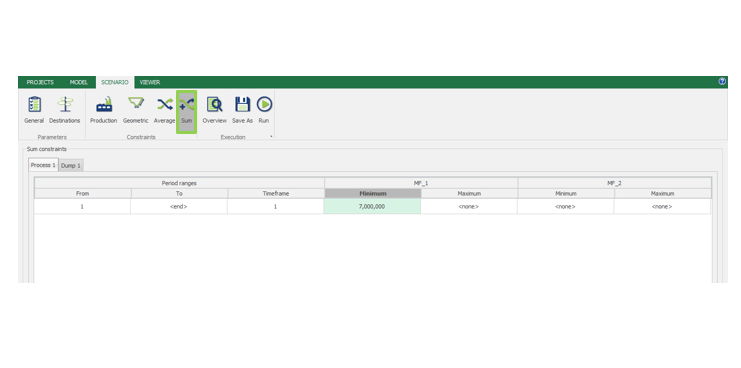

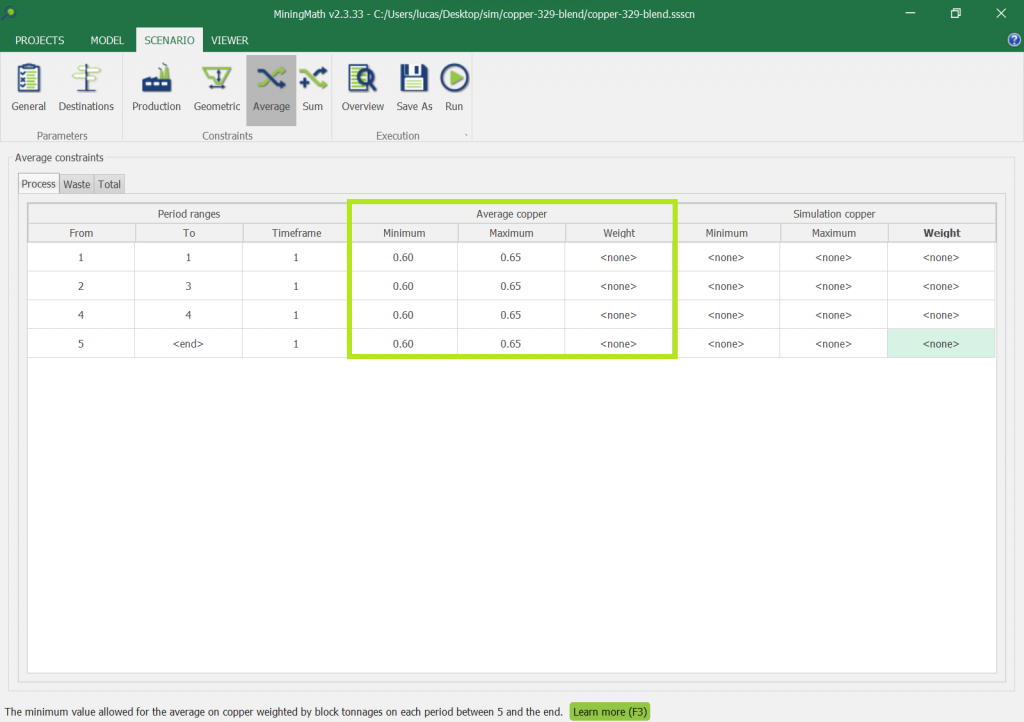

Constraints Validation: Continuing the validation, start to add the first constraints related to your project so that you can understand its maximum potential.

Improve your results

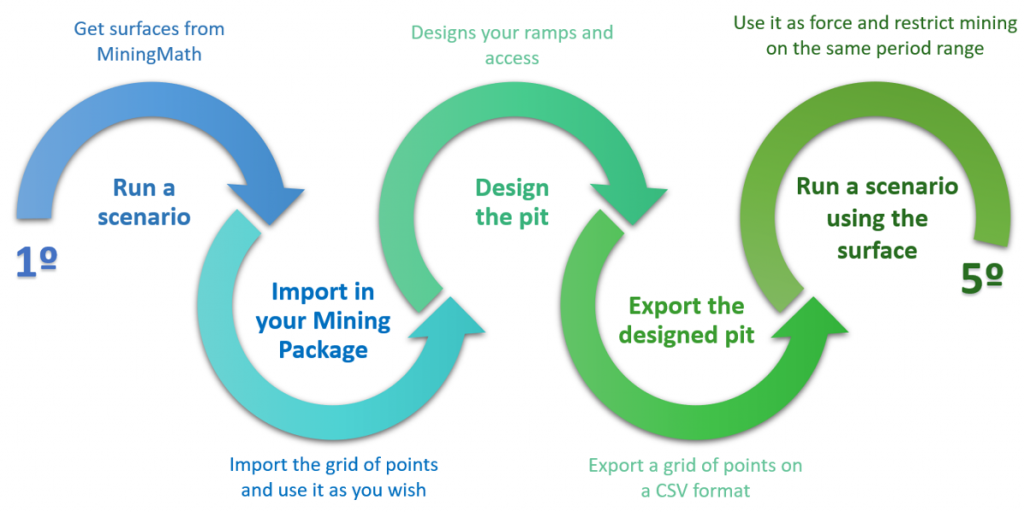

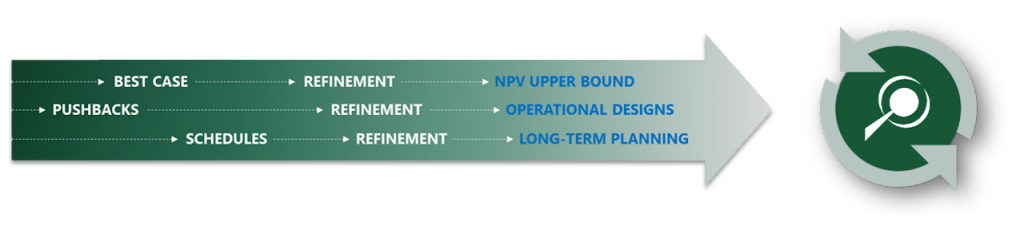

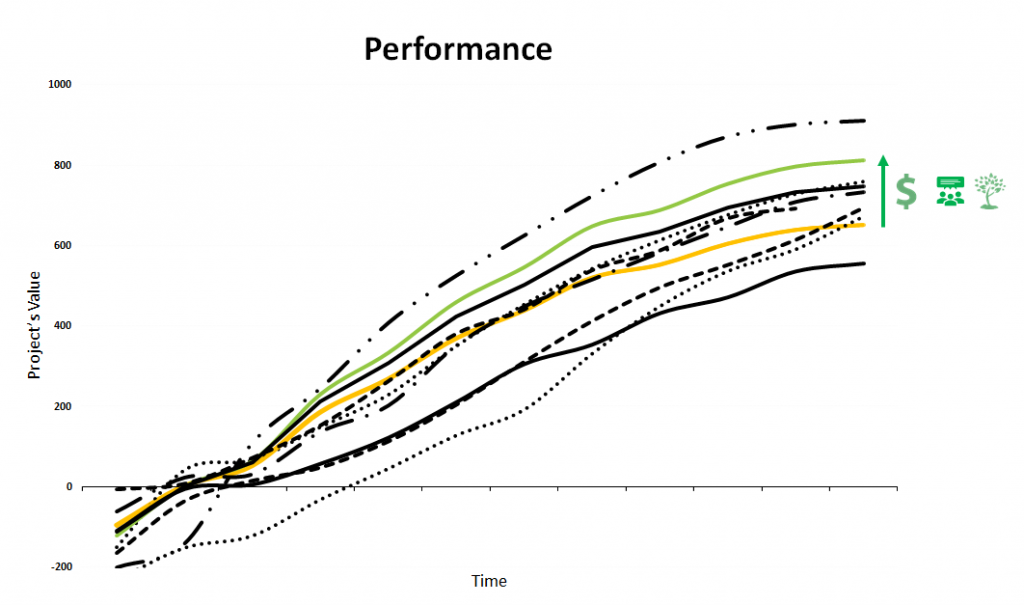

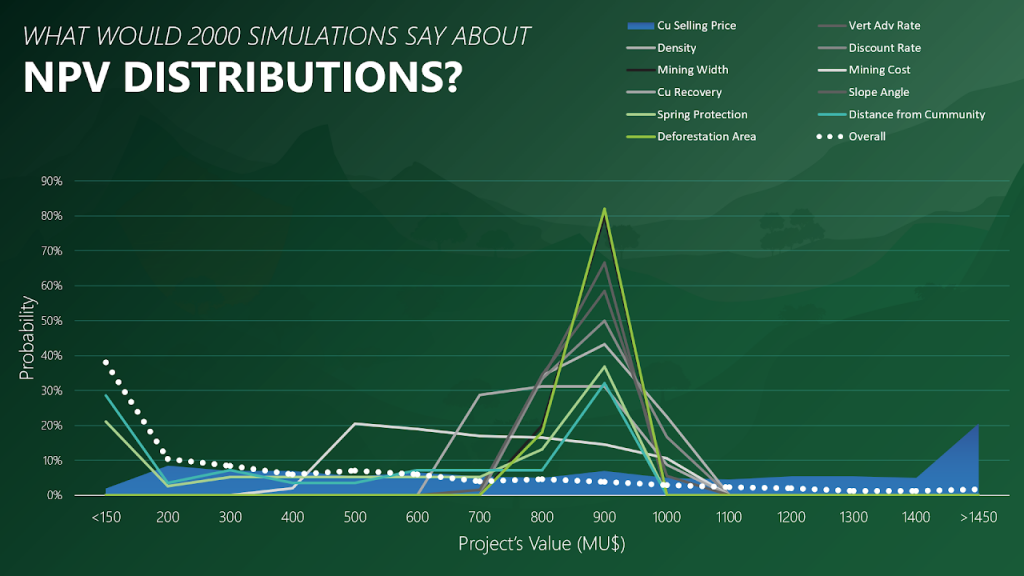

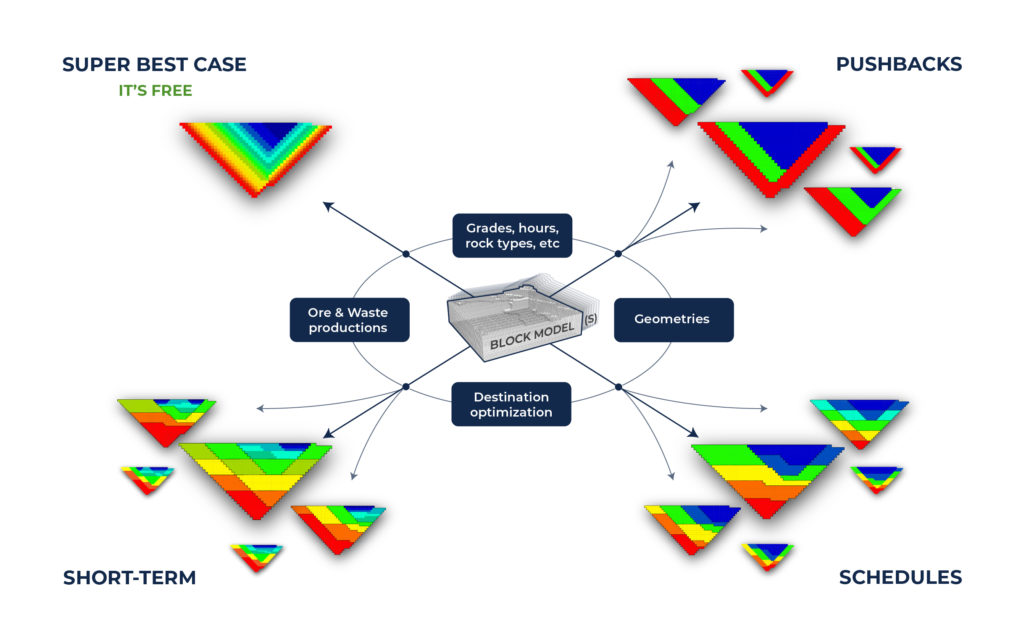

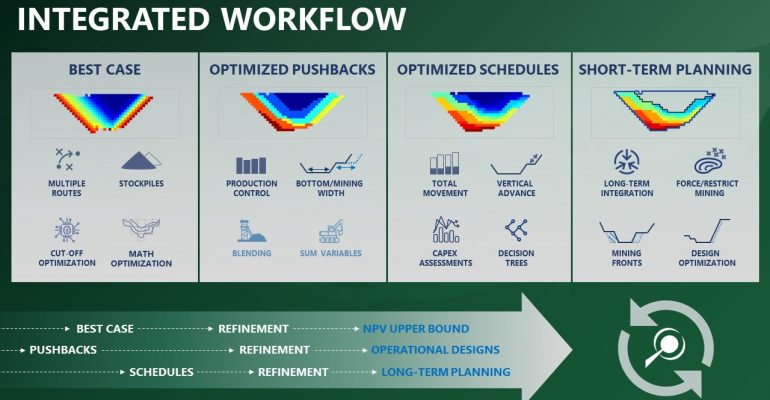

Integrated Workflow: Each project has its own characteristics and MiningMath allows you to choose which workflow fits best in your demand and to decide which one should be used.

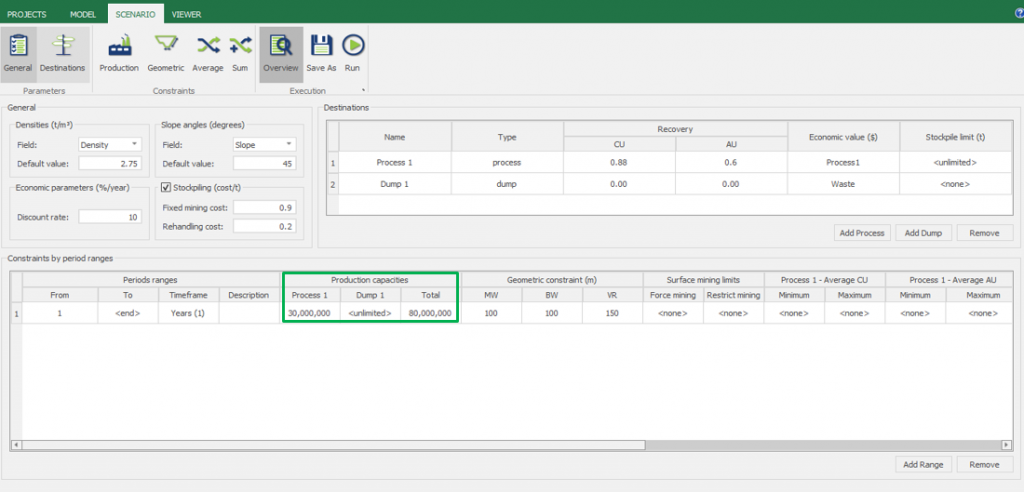

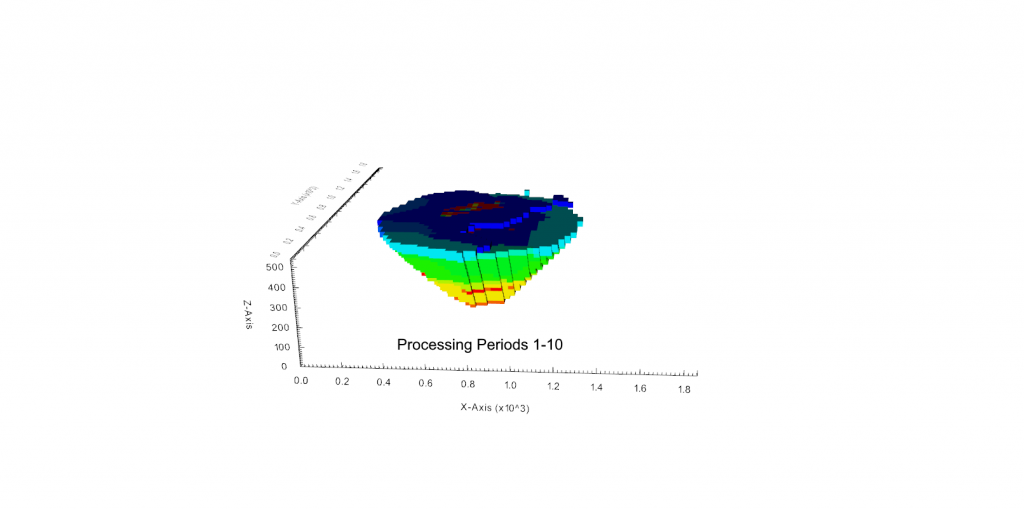

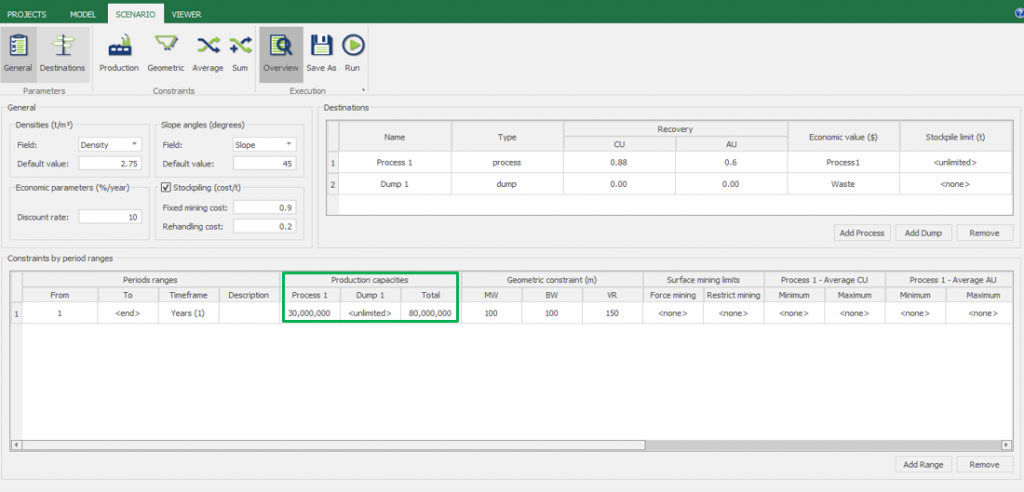

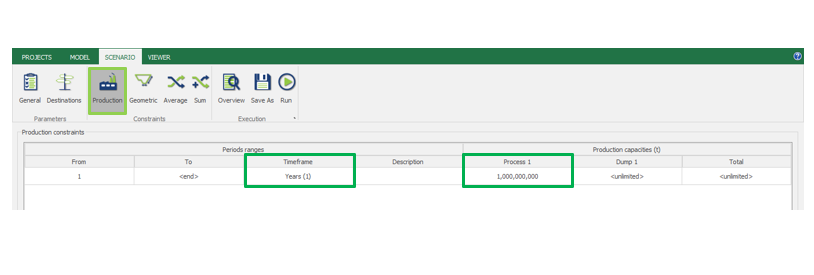

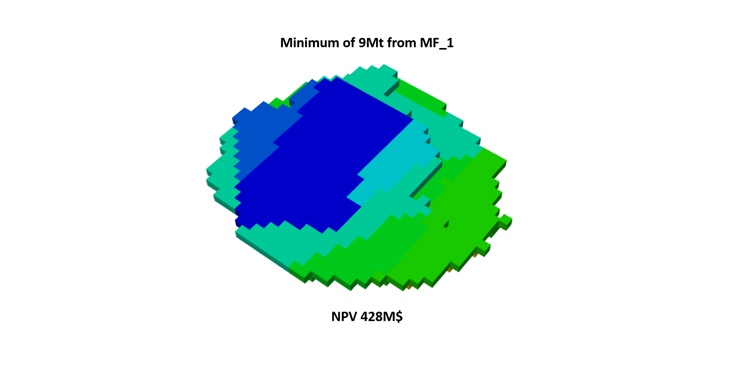

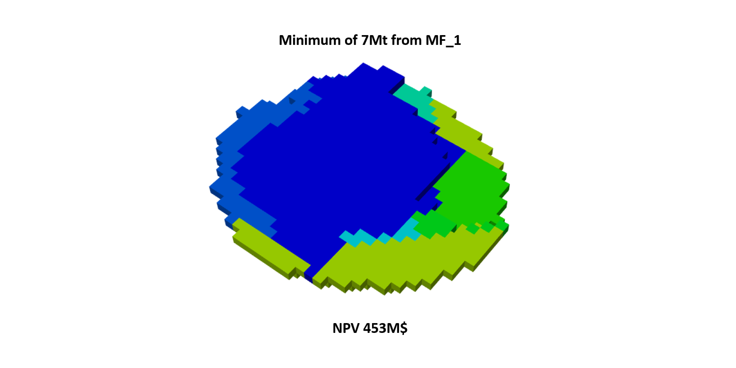

Super Best Case: In the search for the upside potential for the NPV of a given project, this setup explores the whole solution space without any other constraints but processing capacities, in a global multi-period optimization fully focused on maximizing the project’s discounted cash flow.

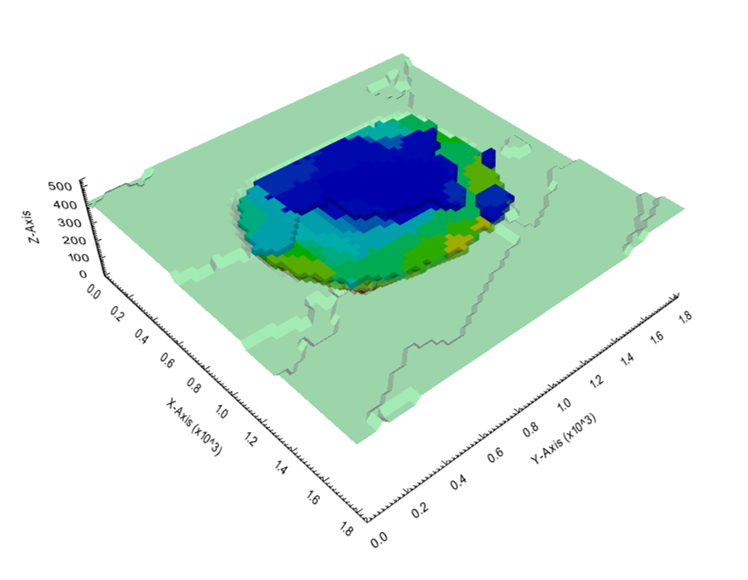

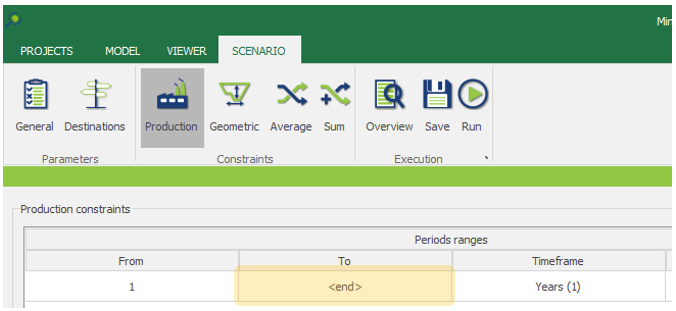

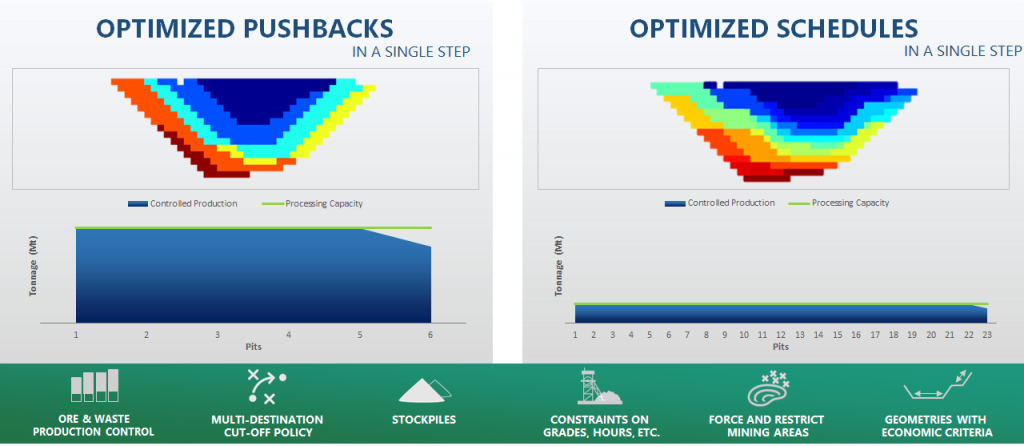

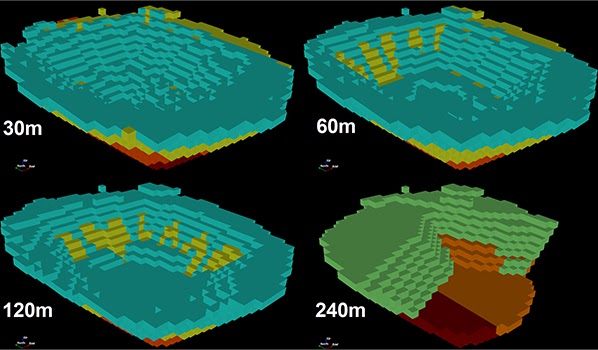

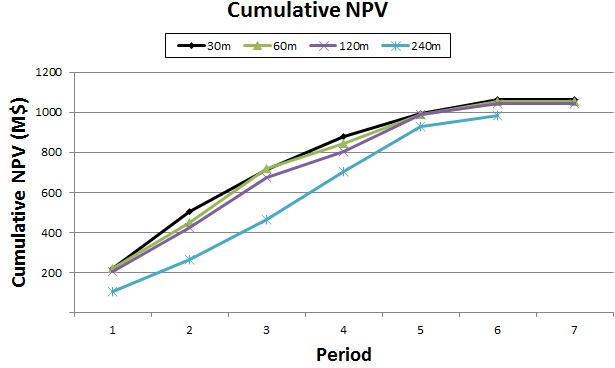

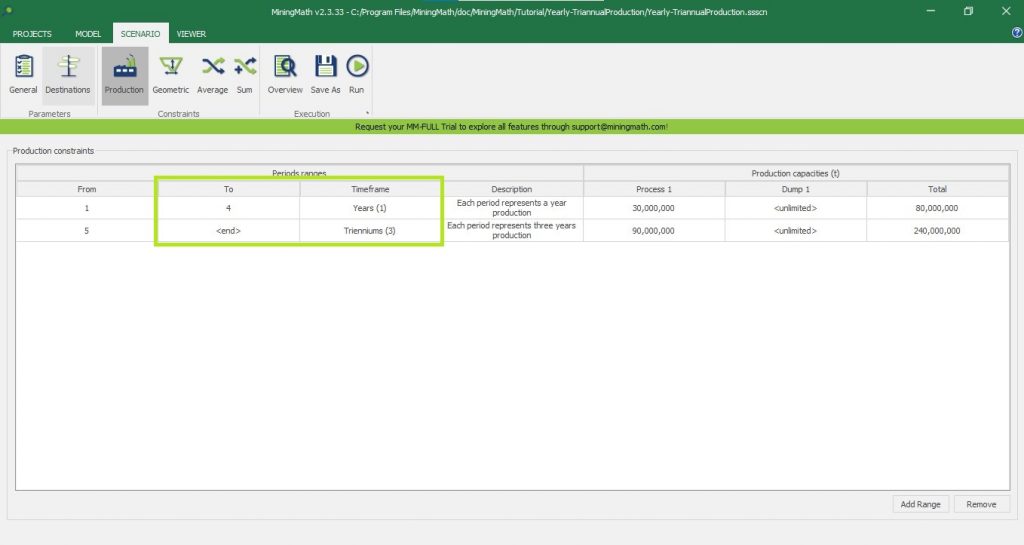

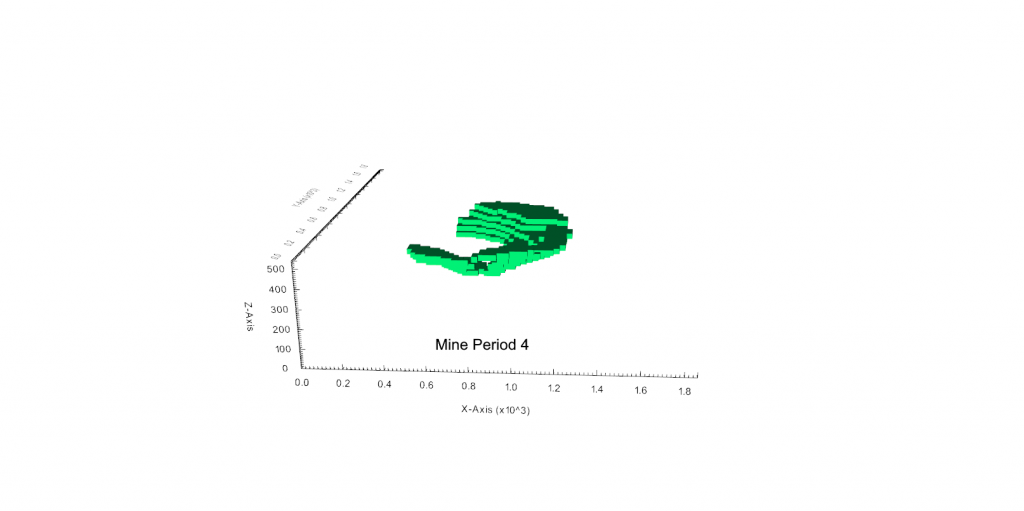

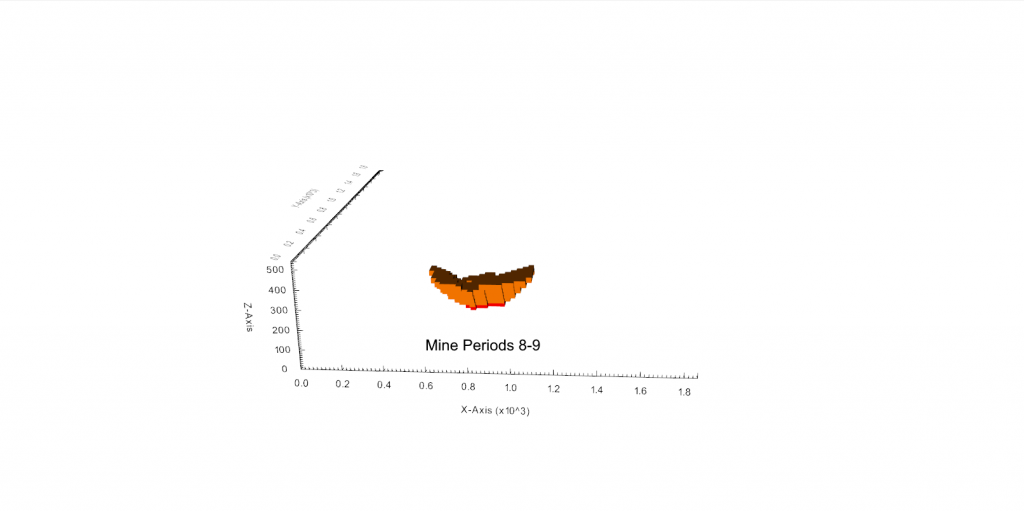

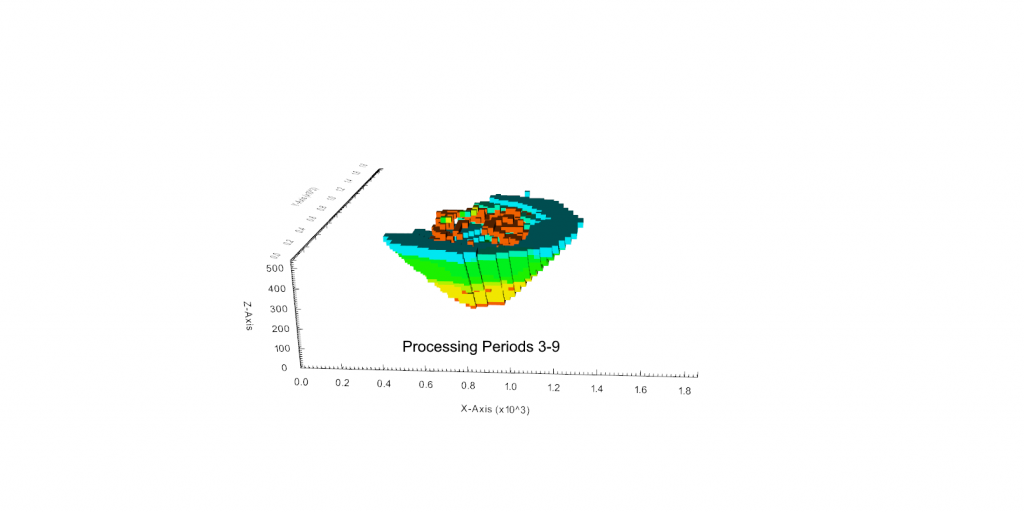

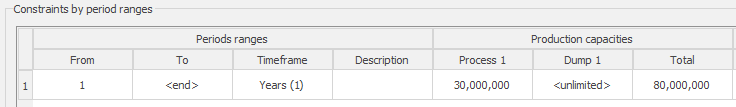

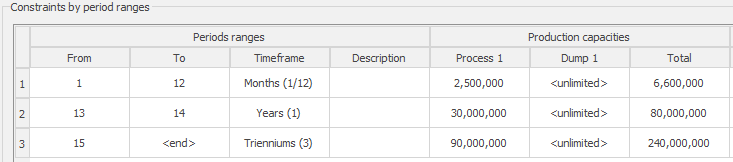

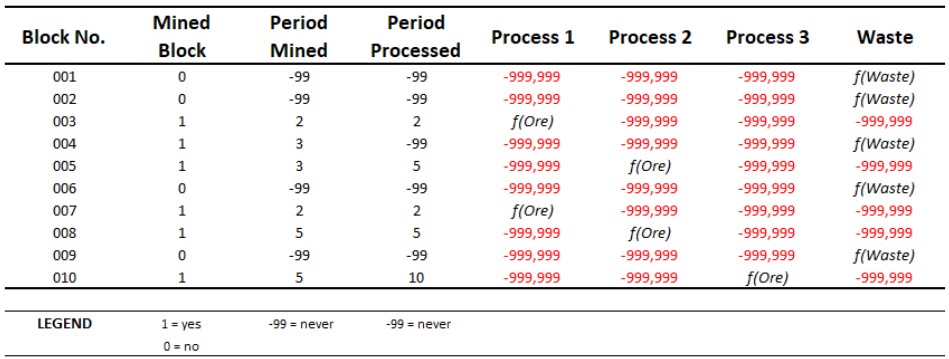

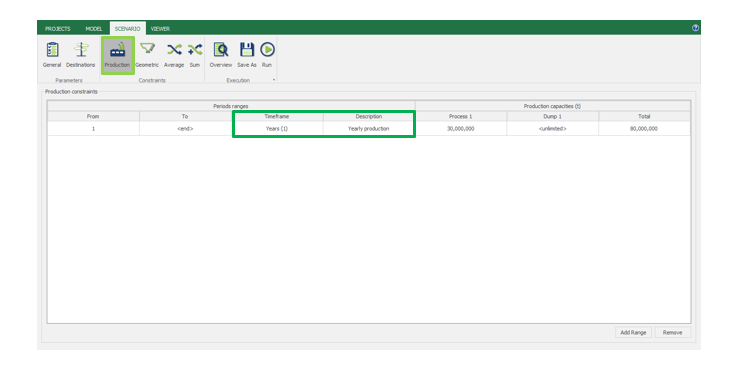

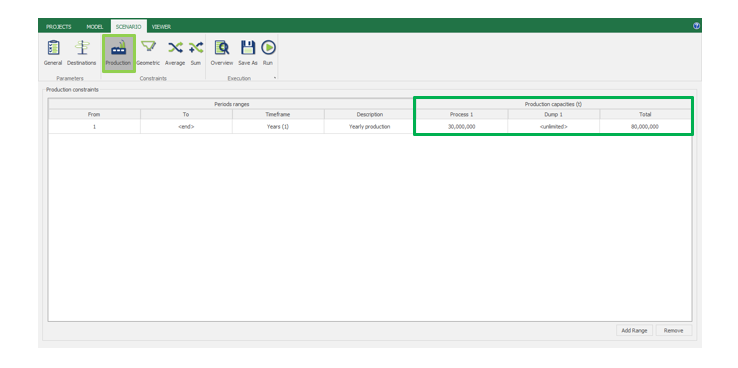

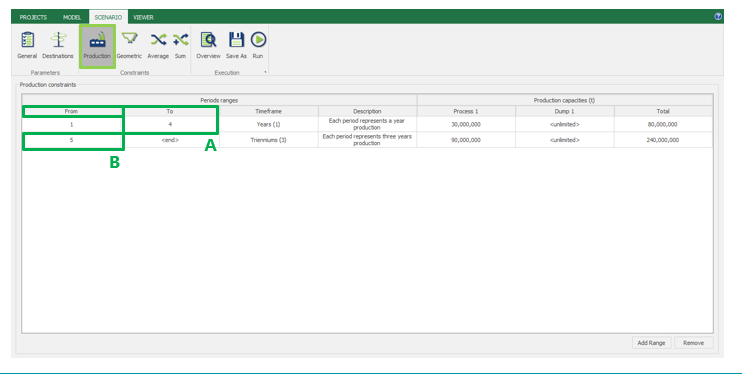

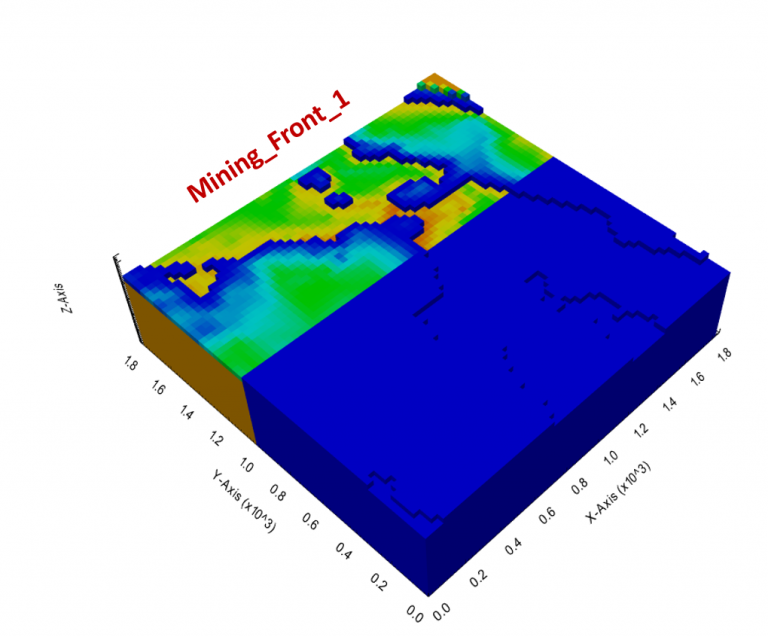

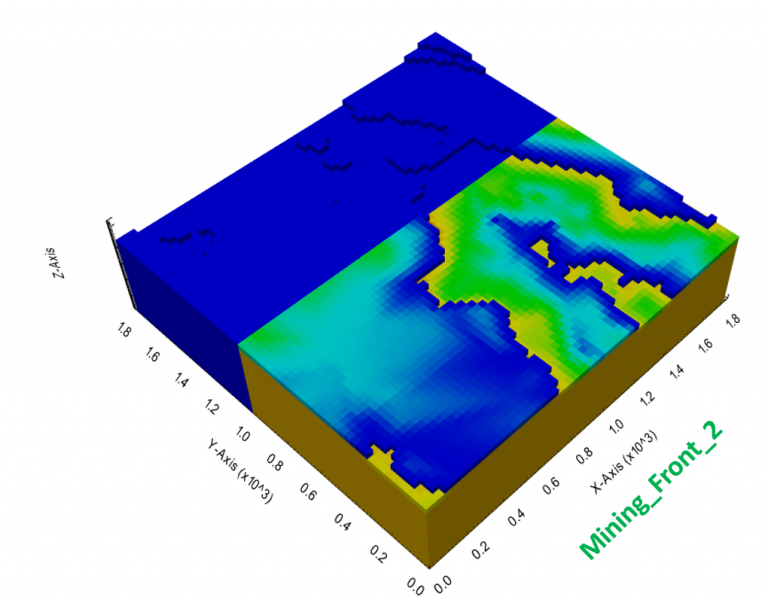

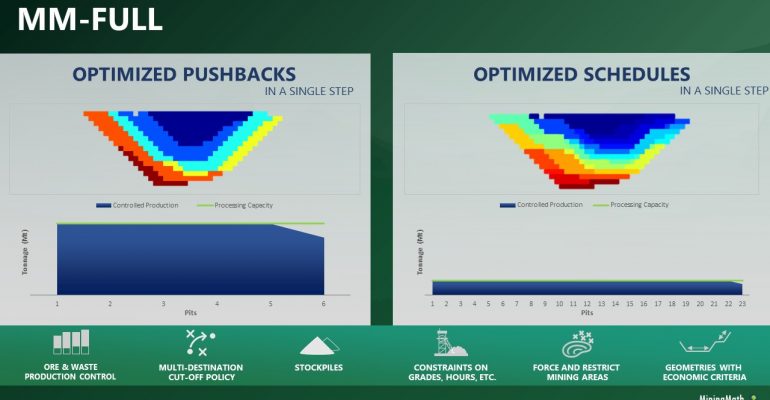

Optimized Pushbacks: Identify timeframe intervals in your project, so that you can work with group periods before getting into a detailed insight. This strategy allows you to run the scenarios faster without losing flexibility or adding dilution on the optimization, which happens when you reblock.

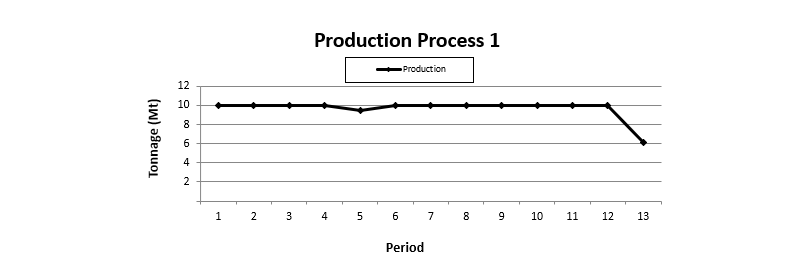

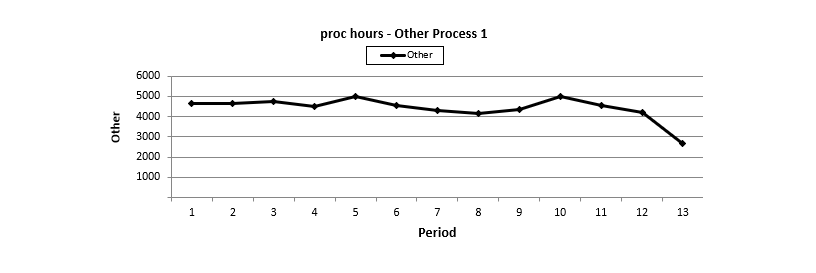

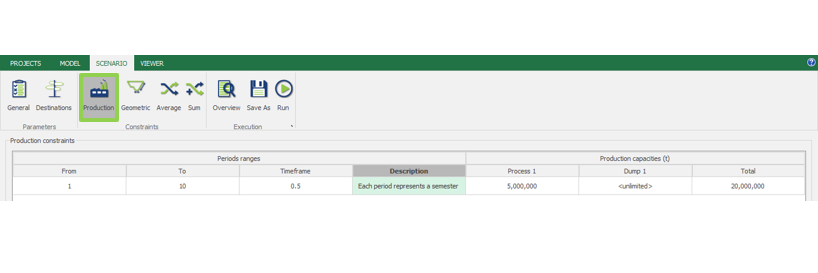

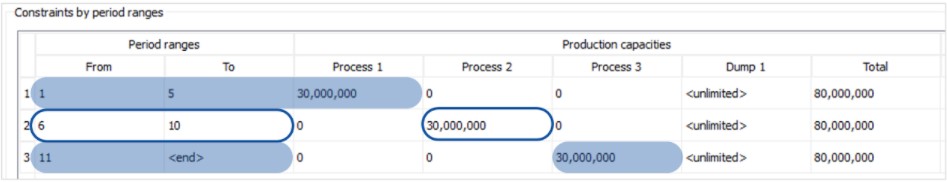

Optimized Schedules: Consider your real production and explore scenarios to the most value in terms of NPV.

Short-term Planning: Now that you built the knowledge about your project based on the previous steps, it is time to start the integration between long and short-term planning in MiningMath. You may also optimize the short-term along with the long-term using different timeframes.

Export your results

Exporting Data: After running your scenarios, you can export all data. Results are automatically exported to CSV files to integrate with your preferred mining package.

In-Depth MiningMath

This tutorial provides a detailed guidance to the pages in the knowledge base for new MiningMath users. A shorter tutorial can be found here with a set of must read articles. In this tutorial, a larger number of pages is contextualized and recommended for those with no previous experience using MiningMath but who wish to gain a more advanced knowledge.

Software requirements

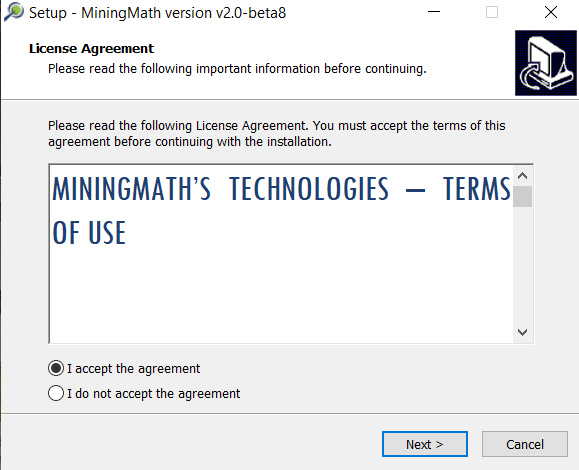

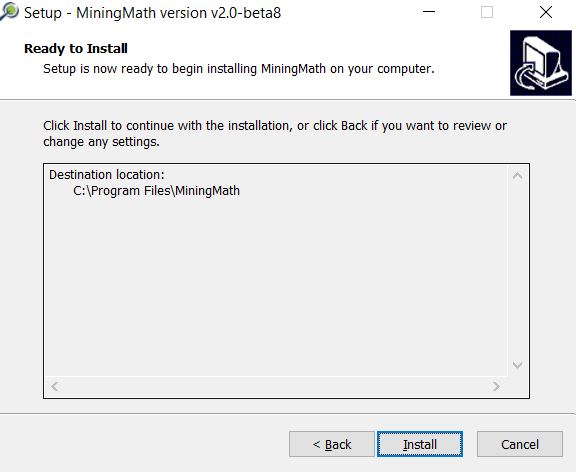

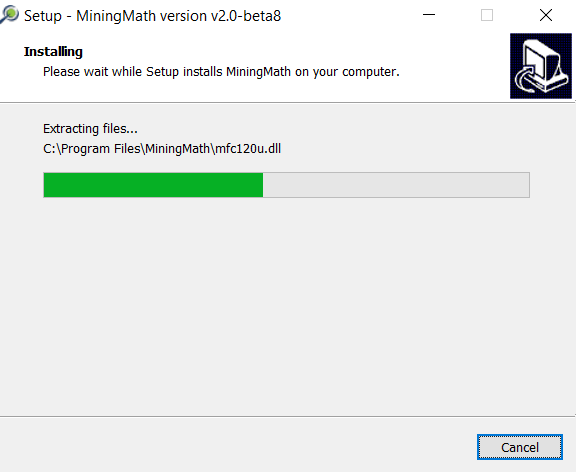

Quick check: Verify if your computer has all the minimum/recommended requirements for running the software.

Put it to run: Here you’ll have all the necessary instructions to install, activate and run MiningMath.

Set up the block model

The next step after installation is to understand the home page interface and import your project data. The following pages go over these in detail.

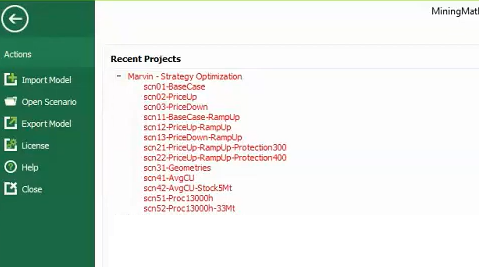

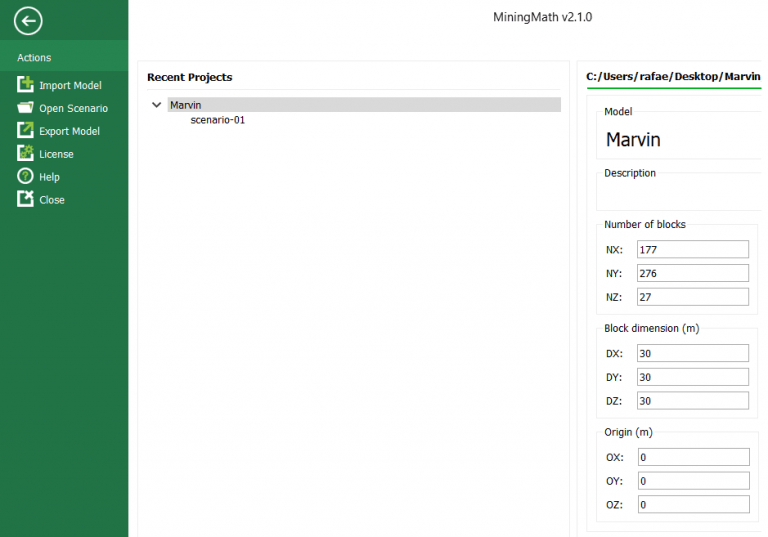

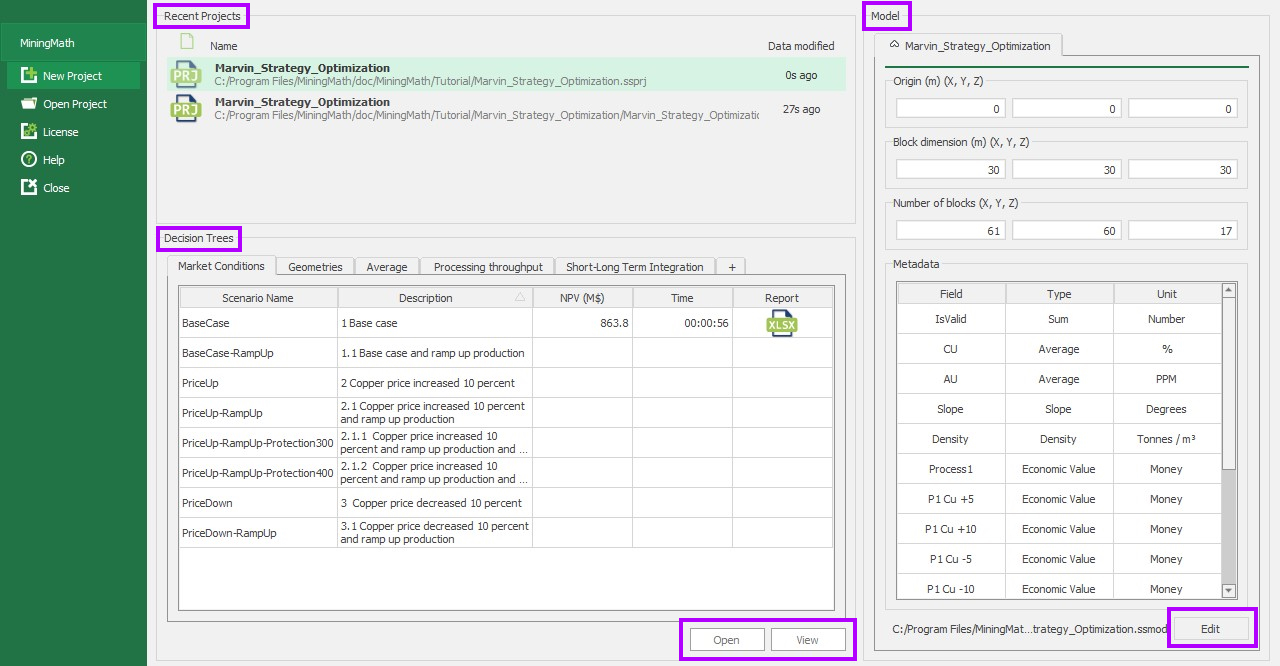

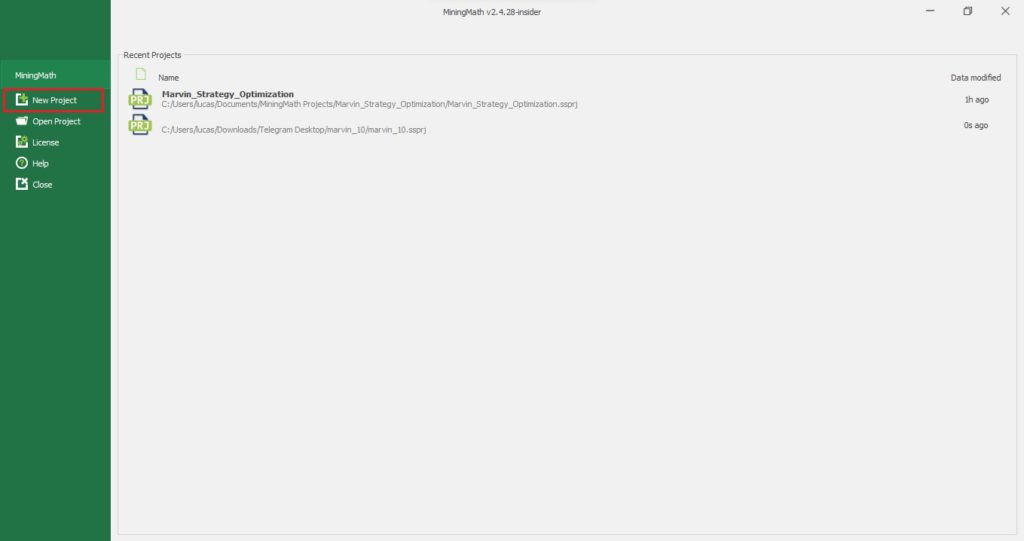

Home page: MiningMath automatically starts on this page. It depicts your decision trees, recent projects and model information.

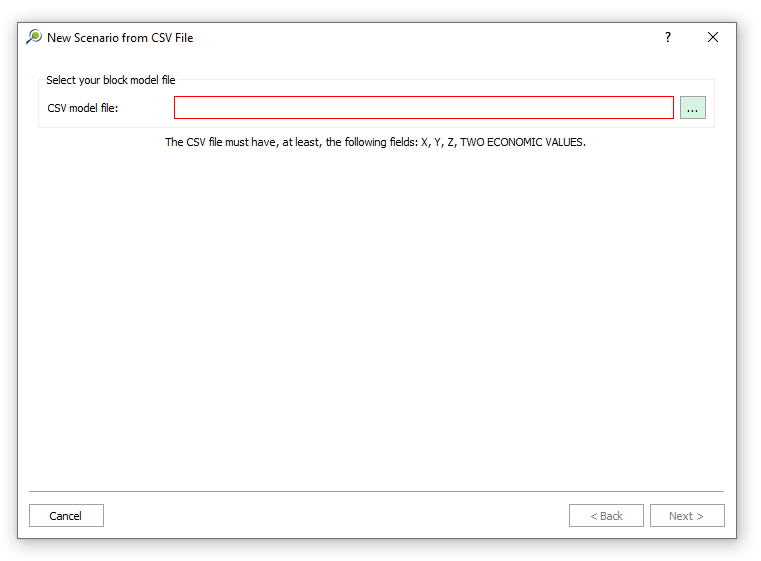

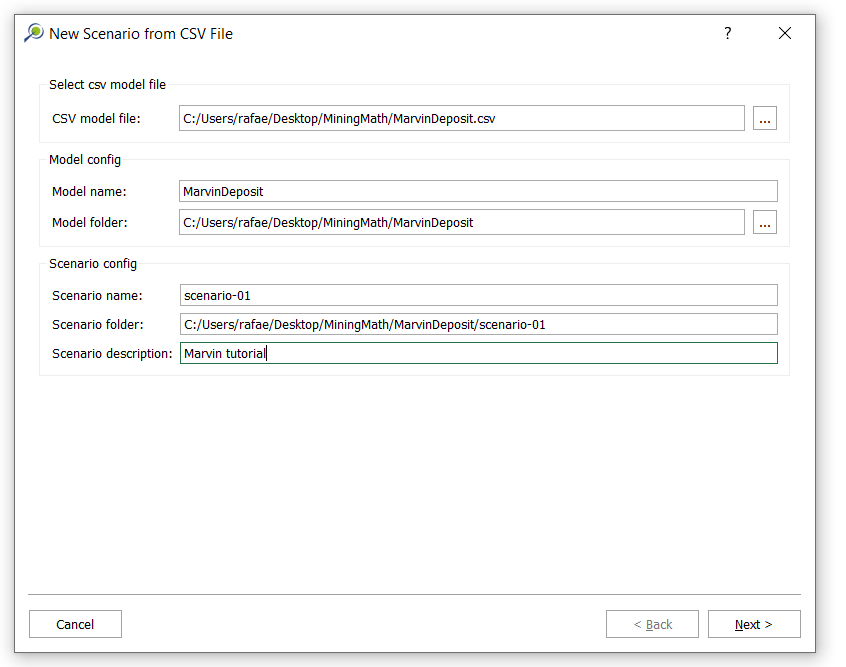

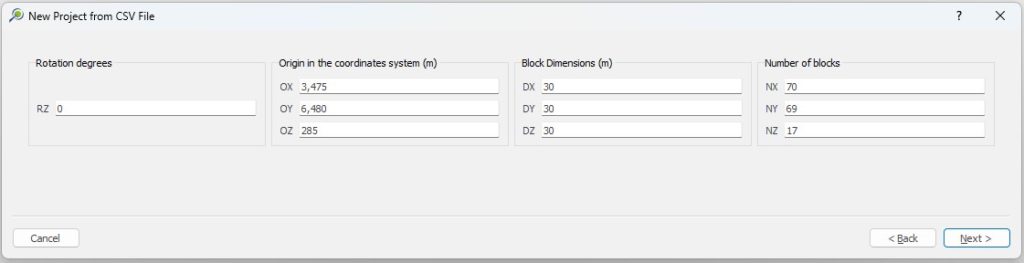

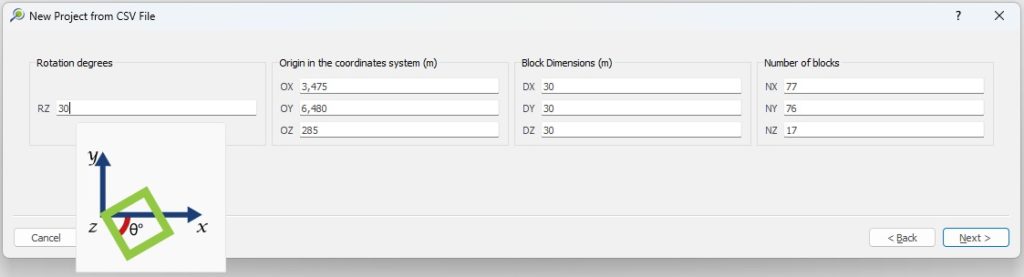

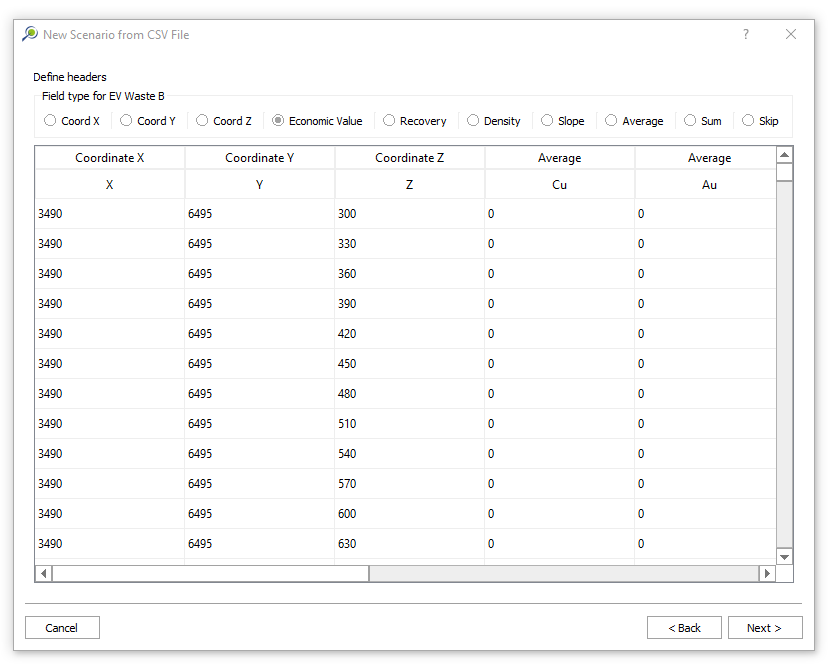

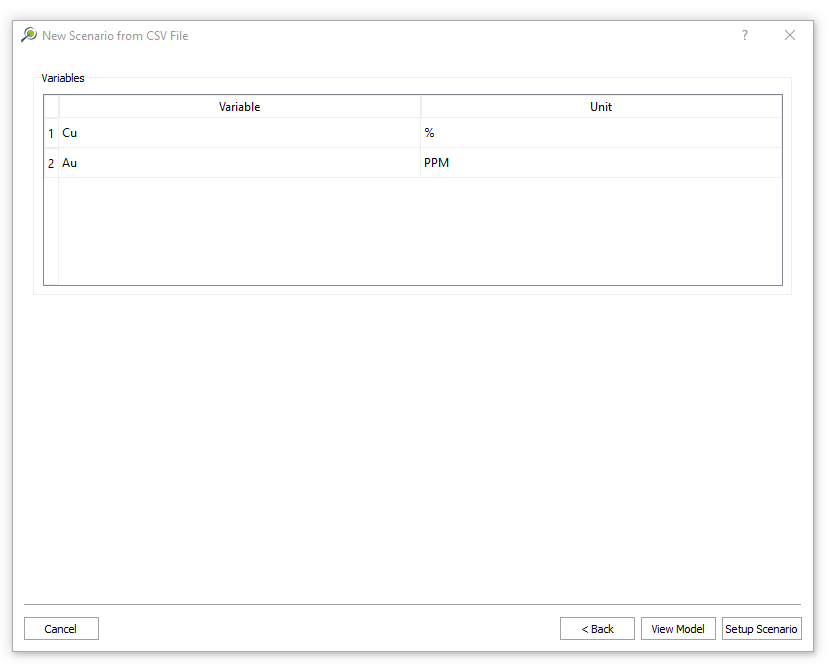

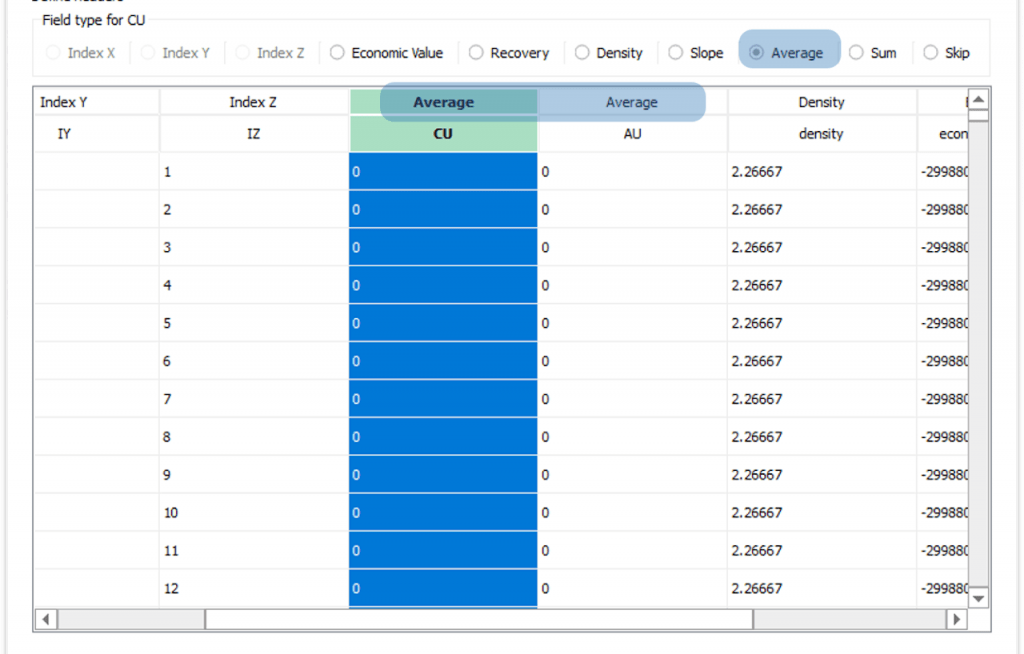

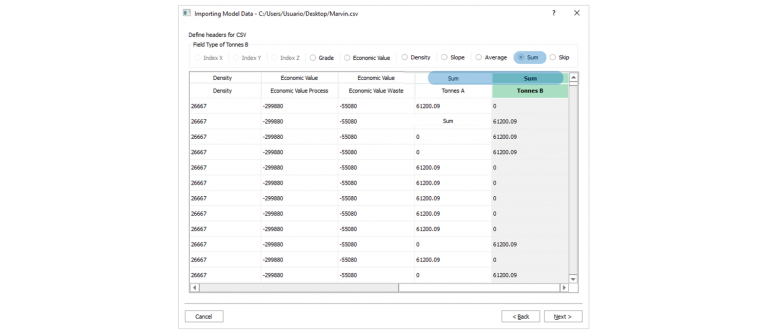

Import your block model: import your

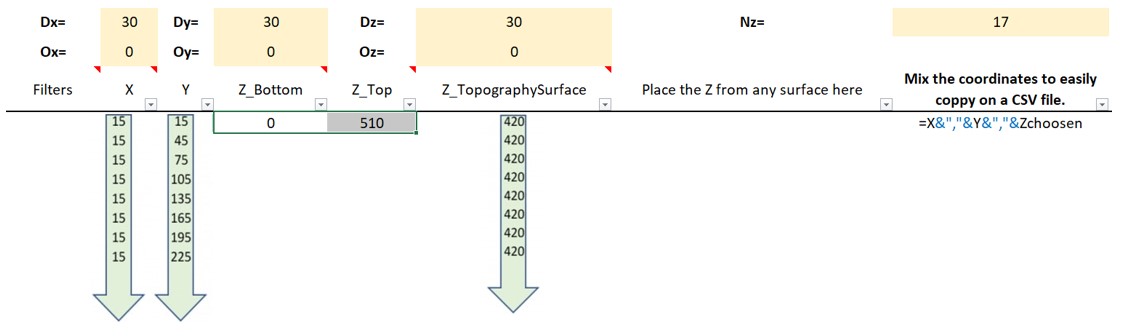

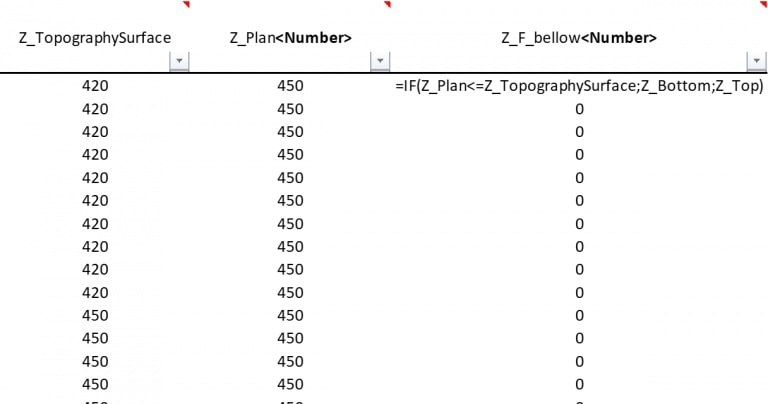

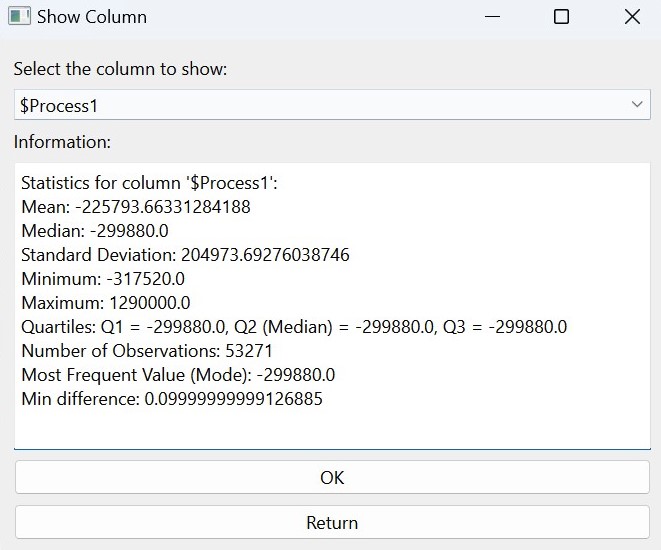

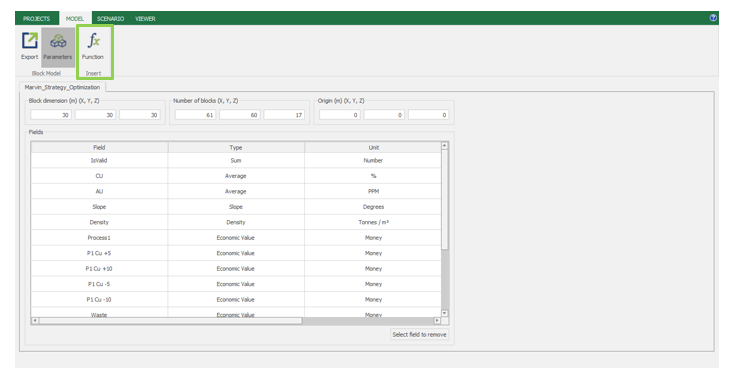

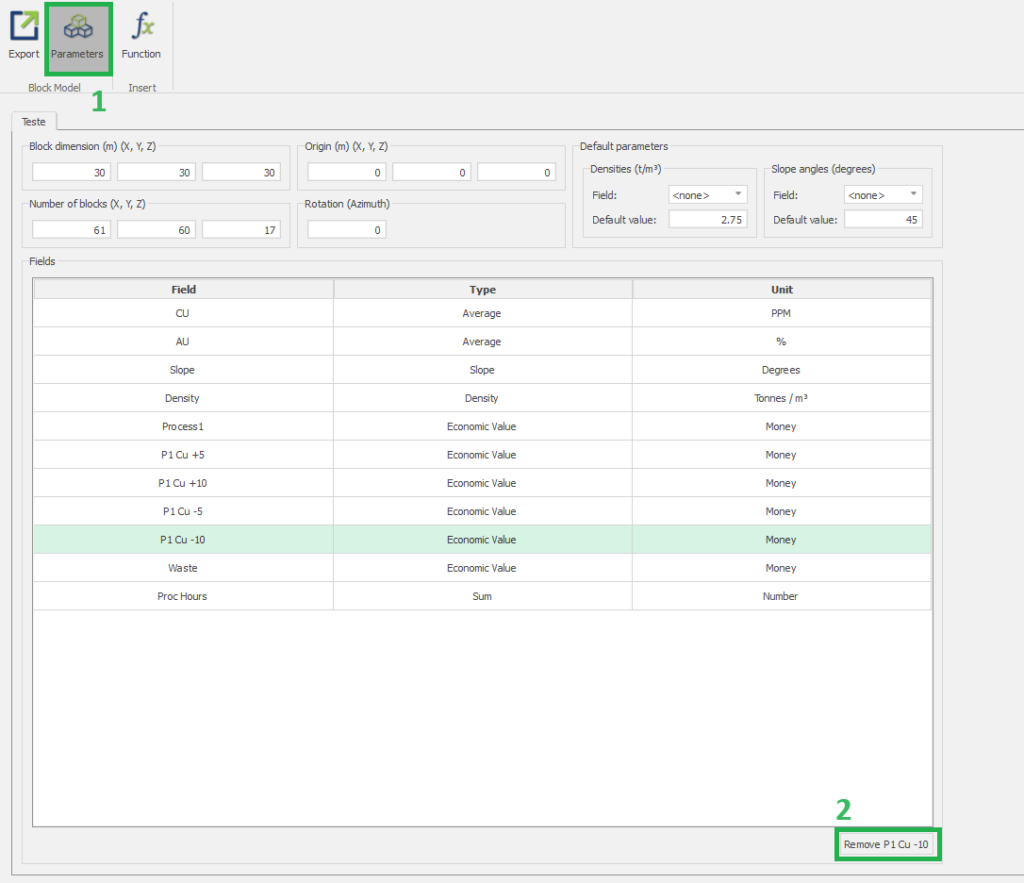

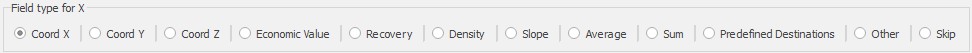

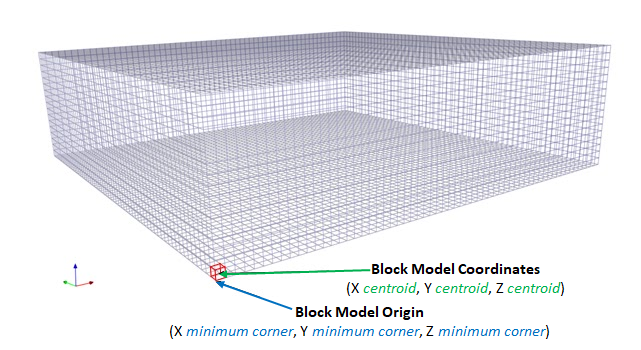

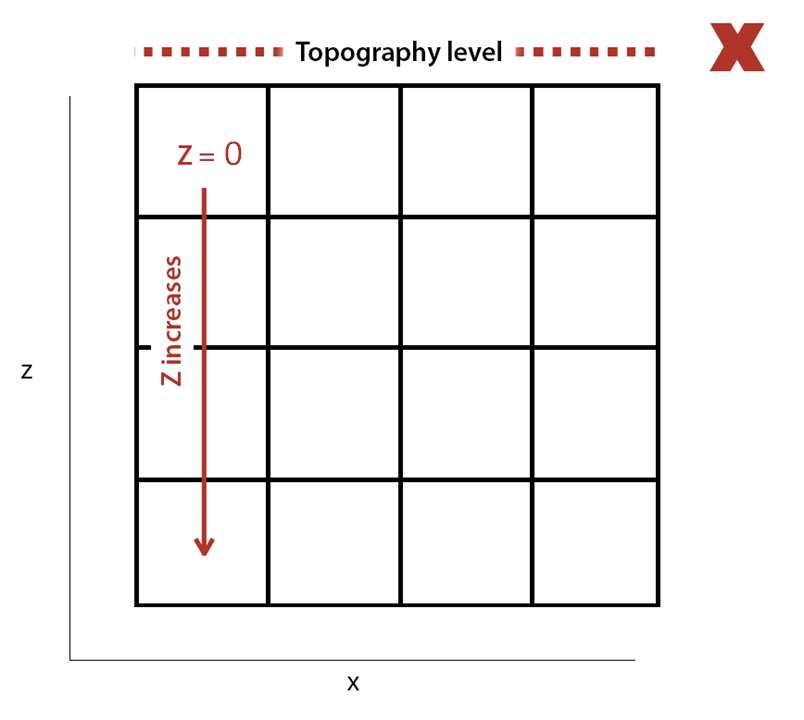

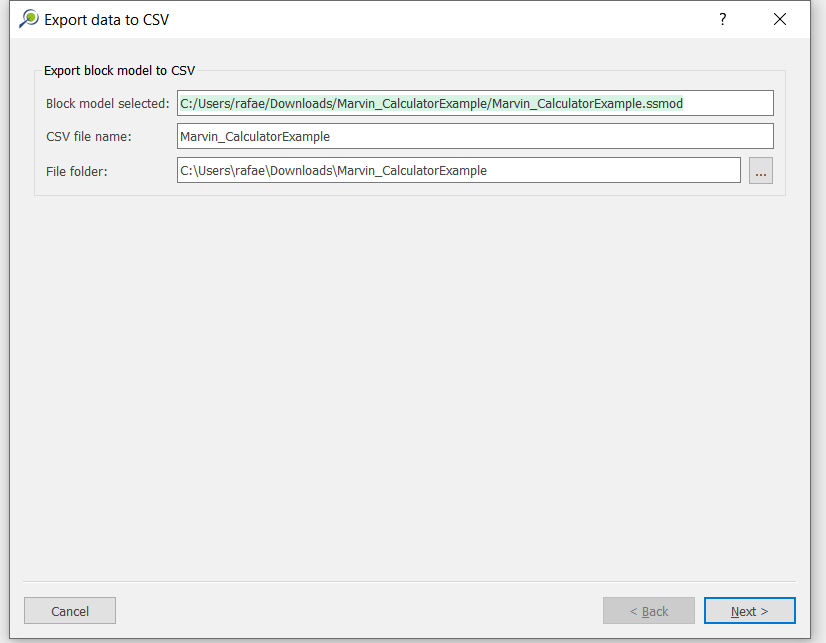

csvdata, name your project, set fields and validation.Modify the block model: this window aims to help you to modify your block model accordingly with what is required for your project and also allows you to “Export” the block model to the CSV format to be used with any other software.

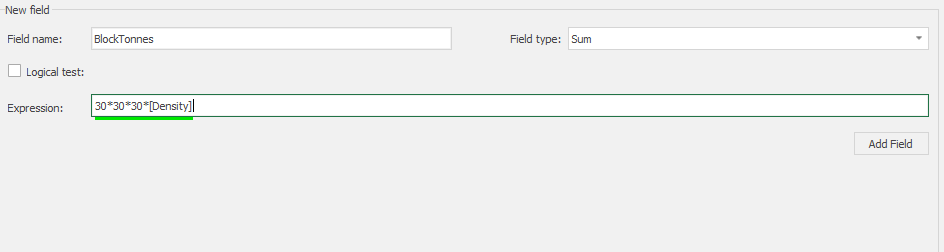

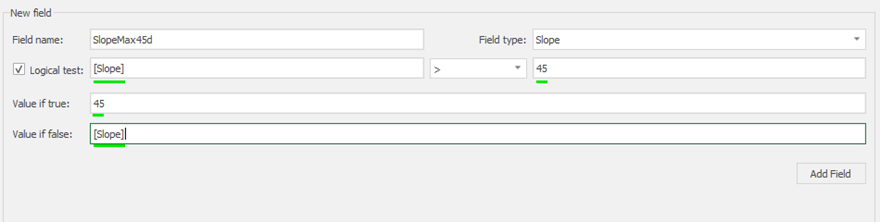

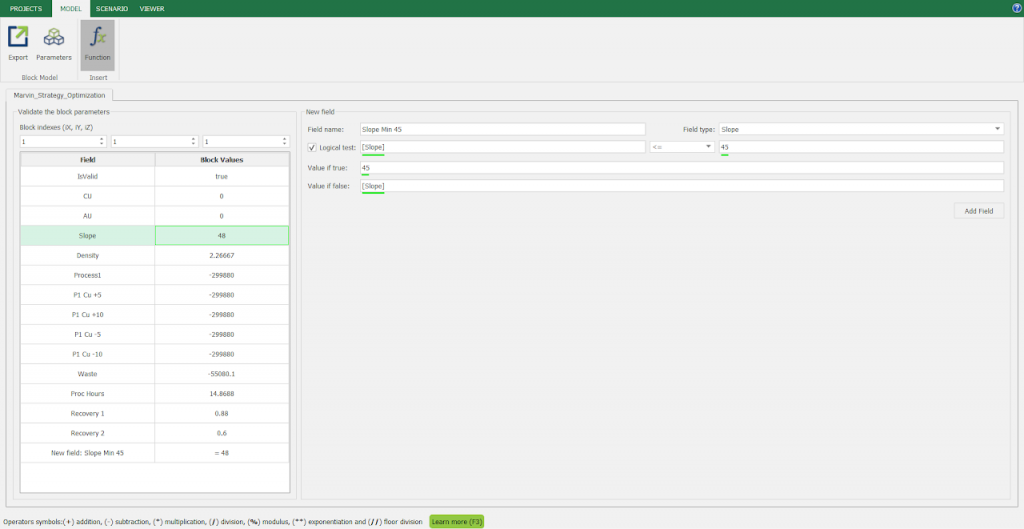

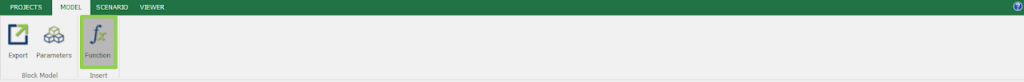

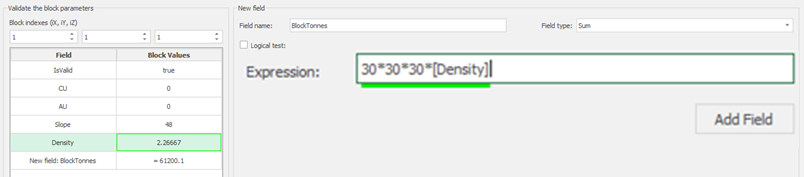

Calculator: calculate and create new fields by manipulating your project inside MiningMath.

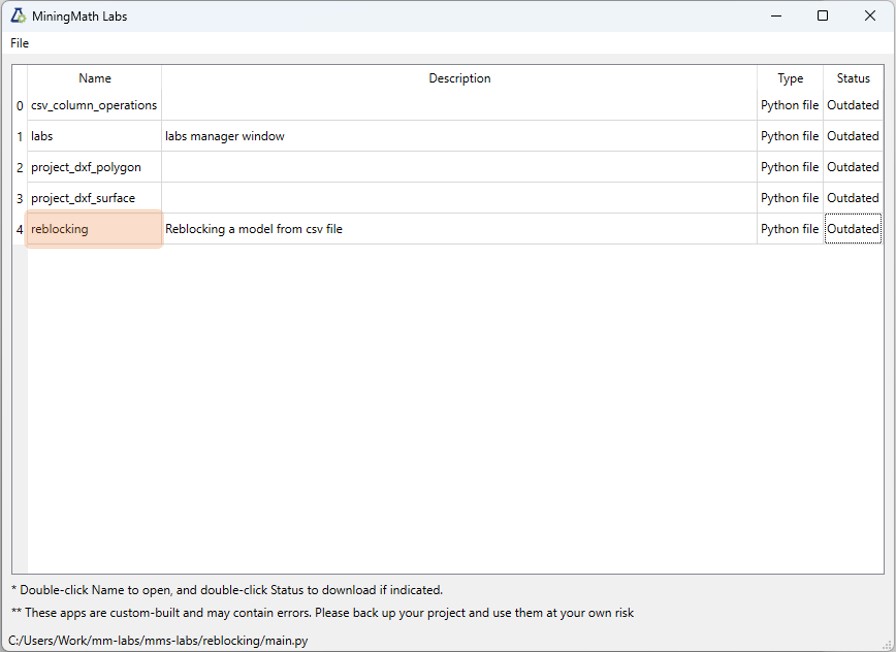

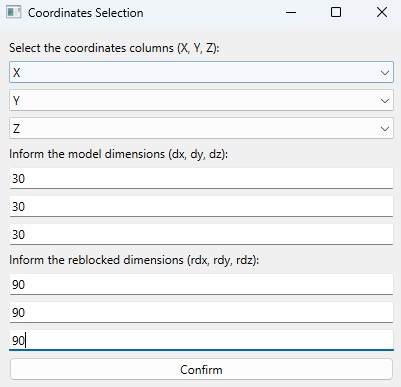

Handling unformatted data

If you don’t have a block model ready to be imported you might want to create a new one. The following pages can guide you through this process.

Define the scenario and run

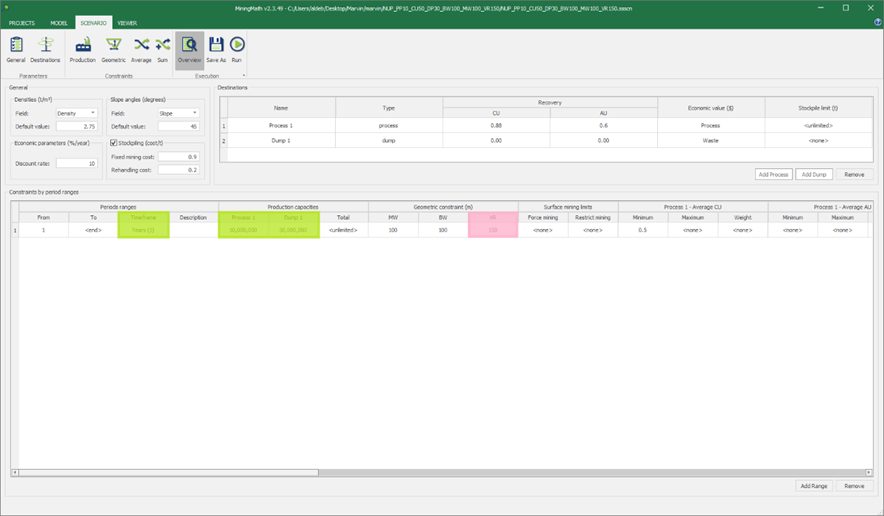

Once you have started your block model defined, there are several options to set up your project’s parameters before running a scenario.

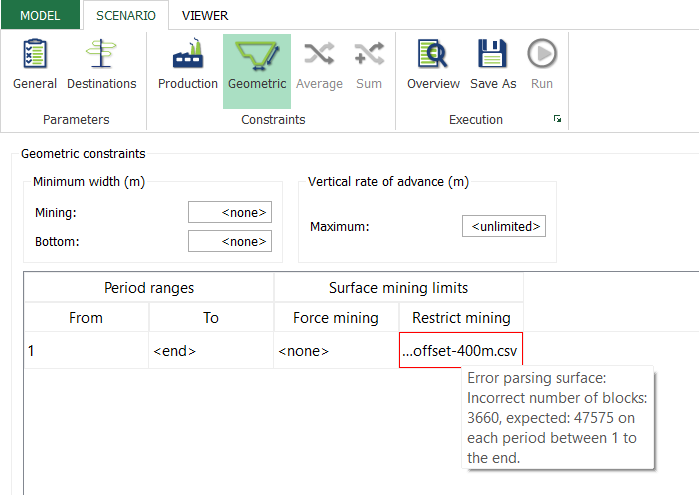

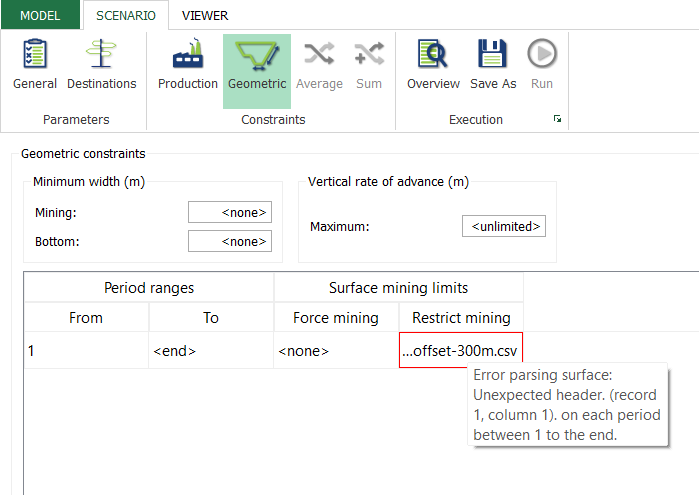

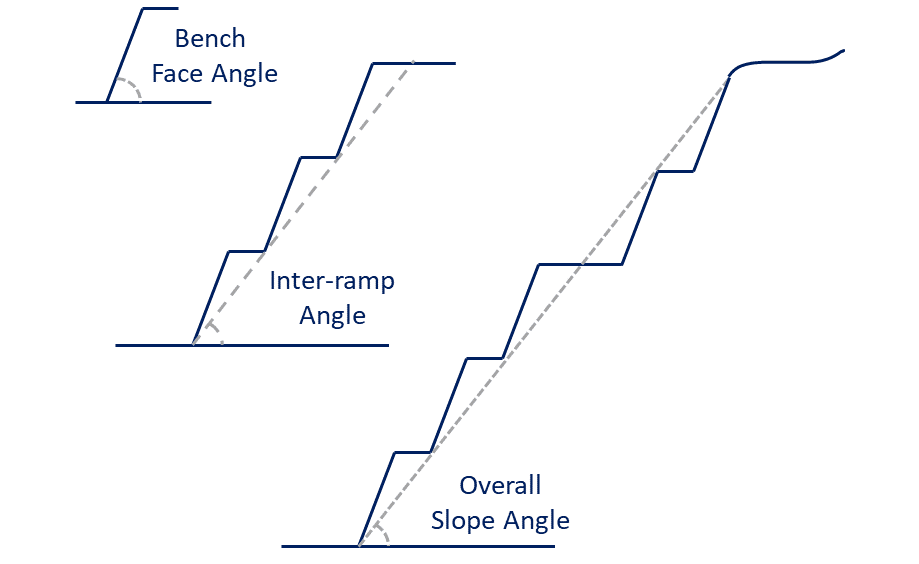

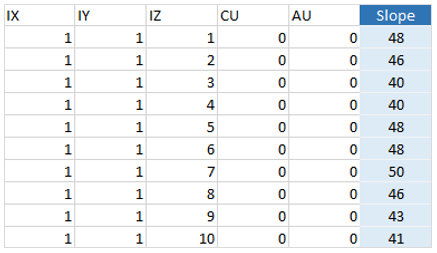

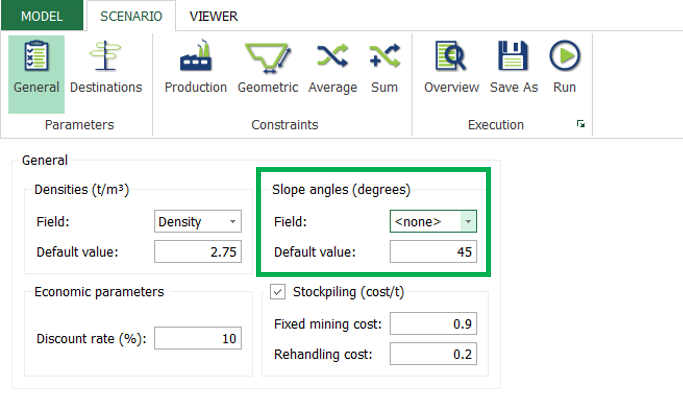

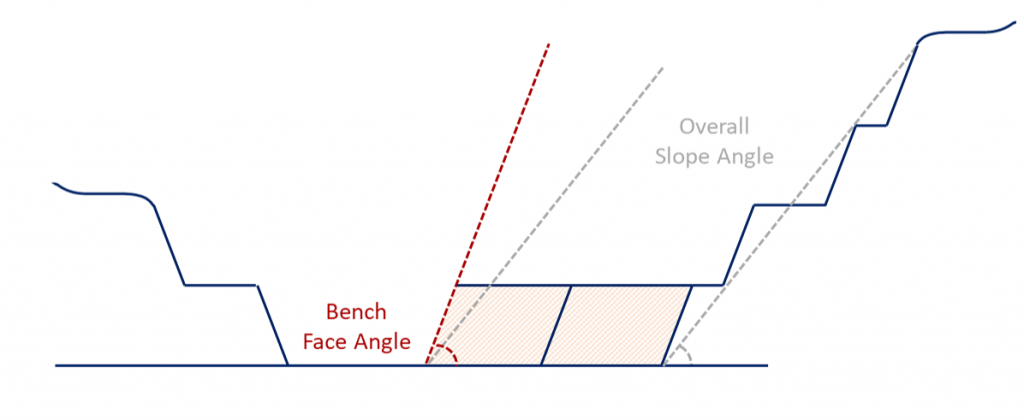

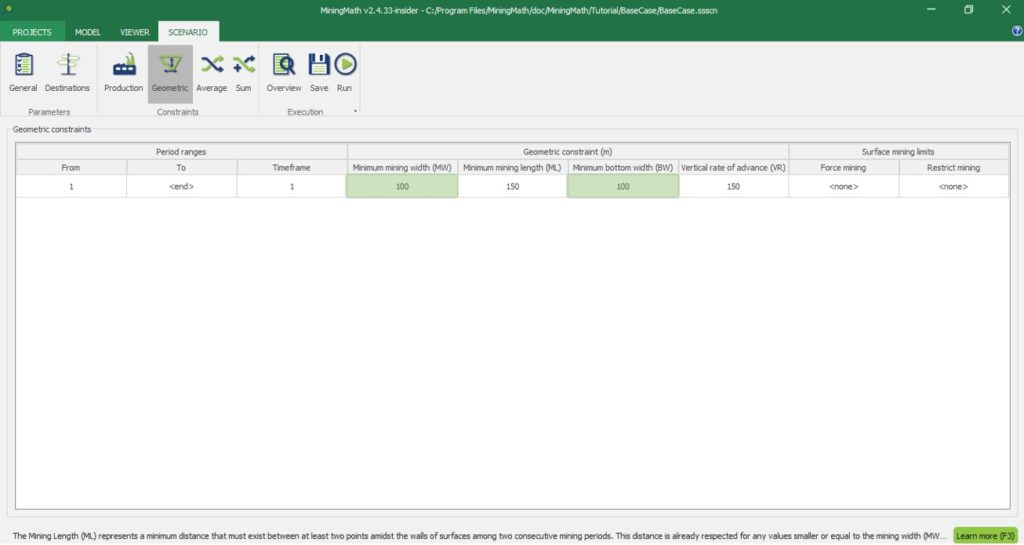

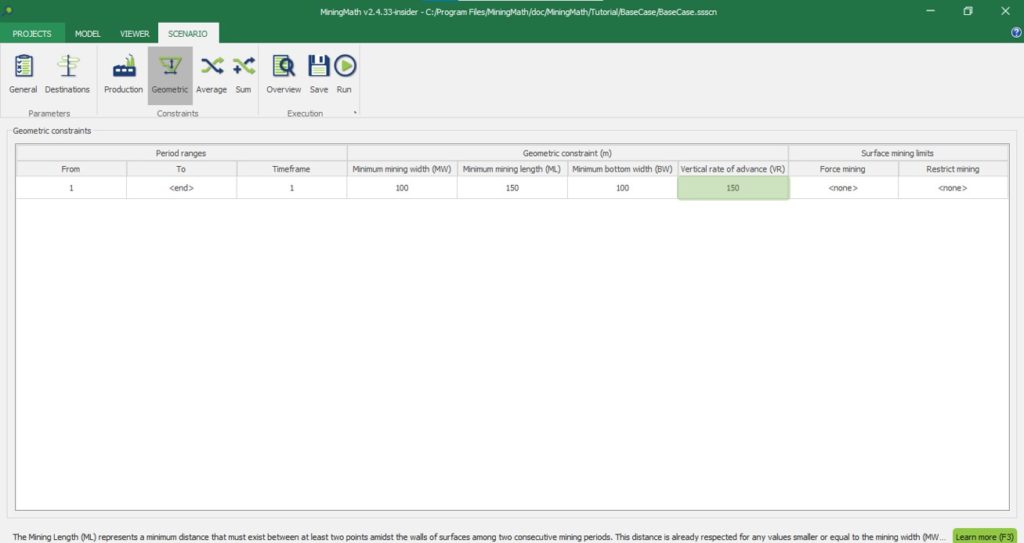

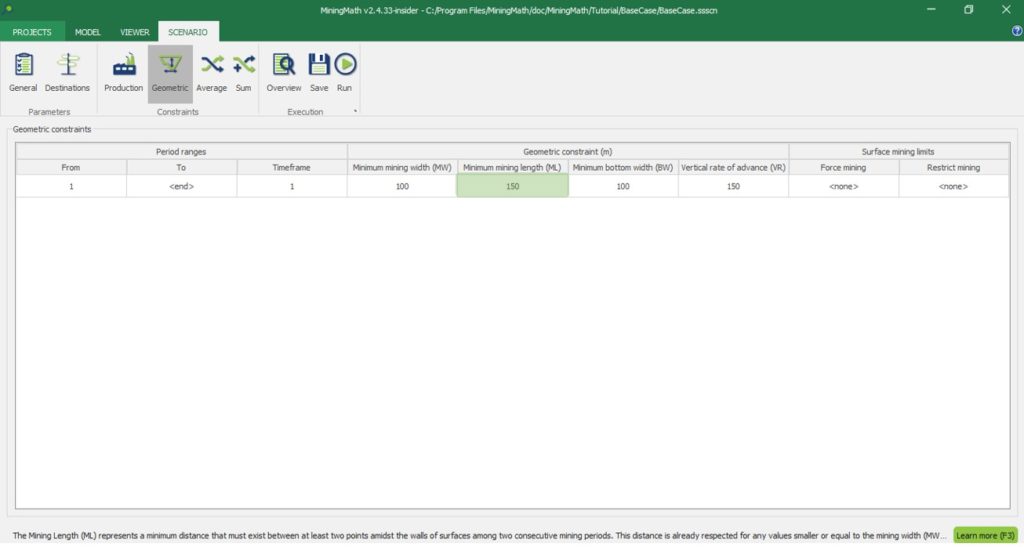

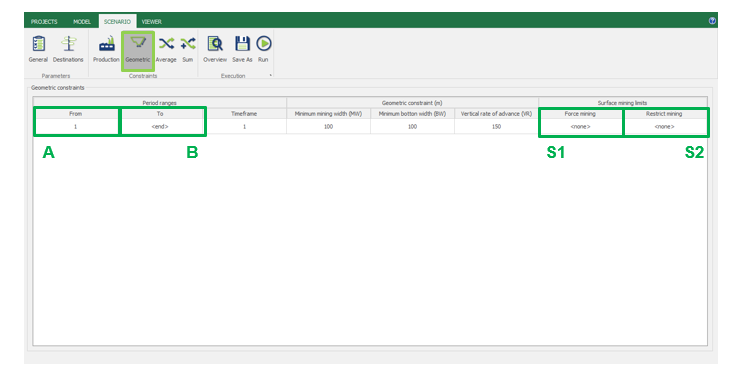

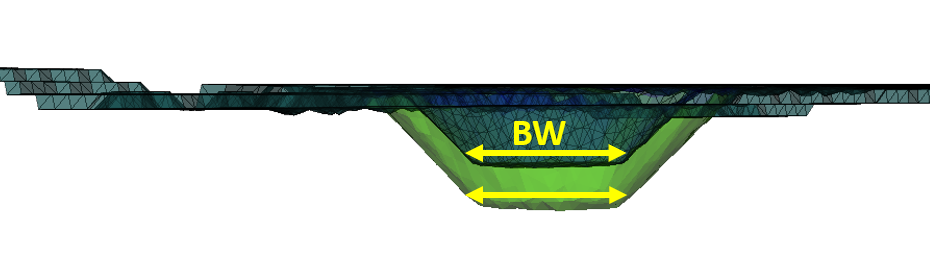

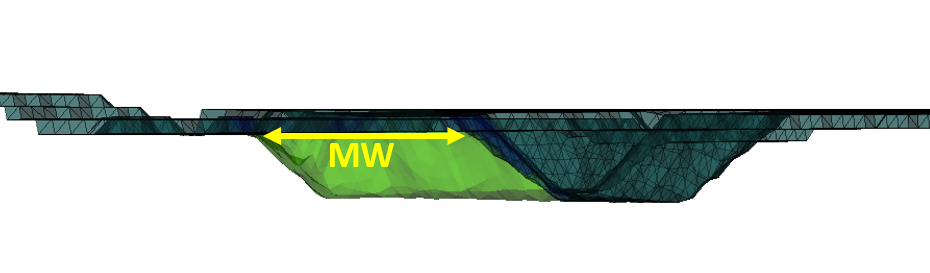

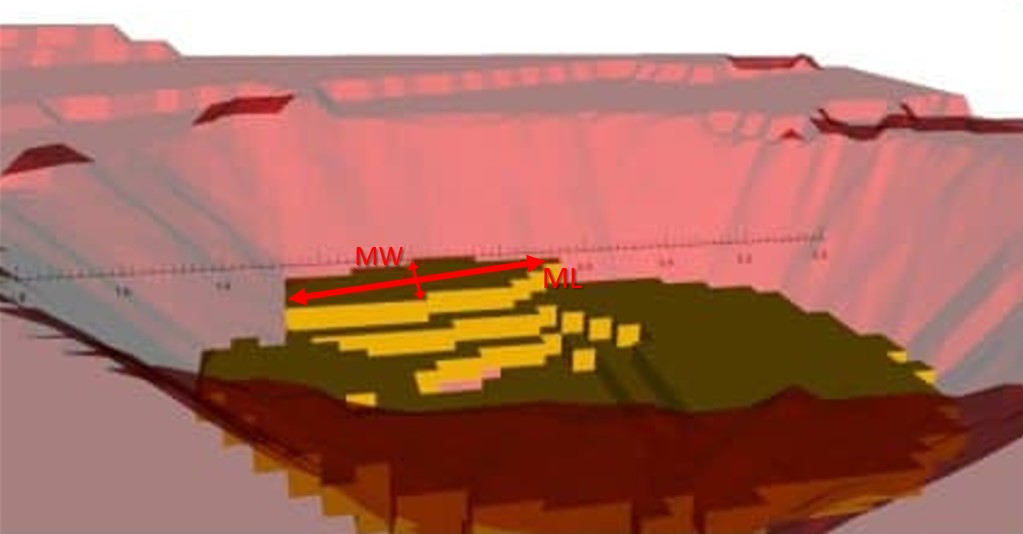

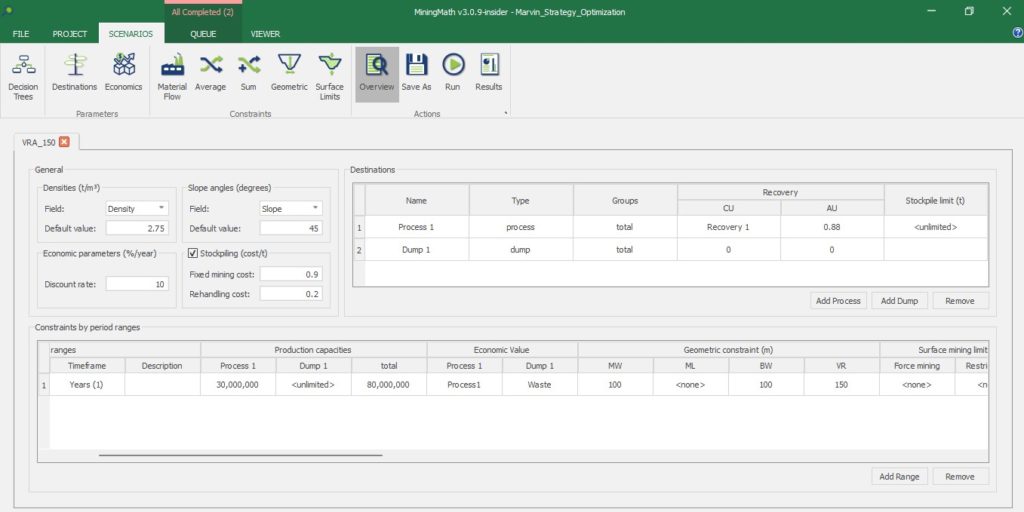

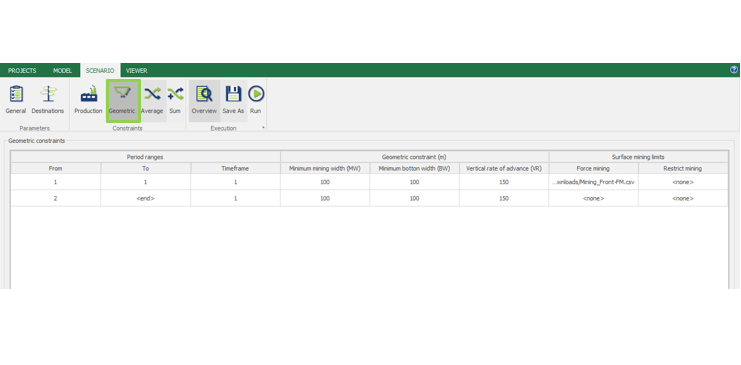

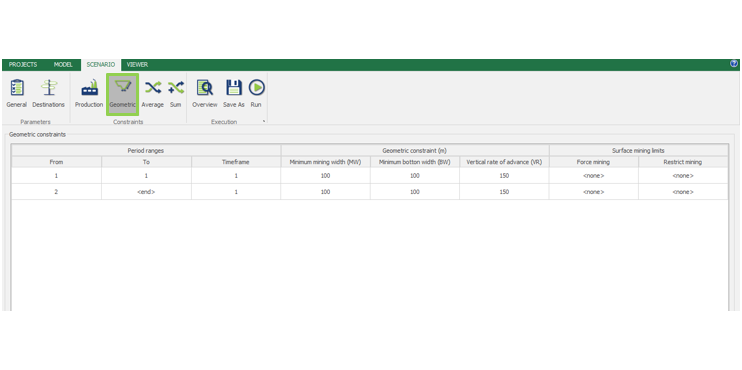

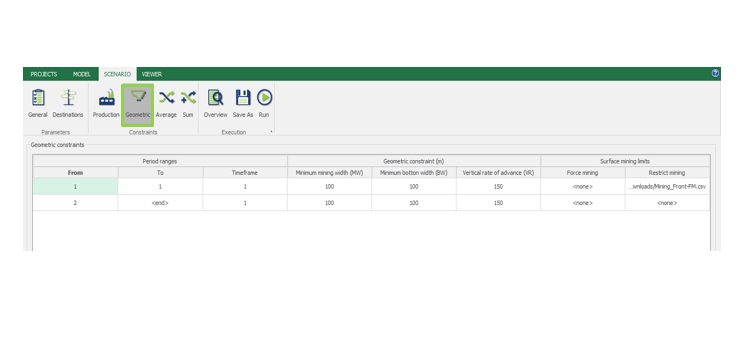

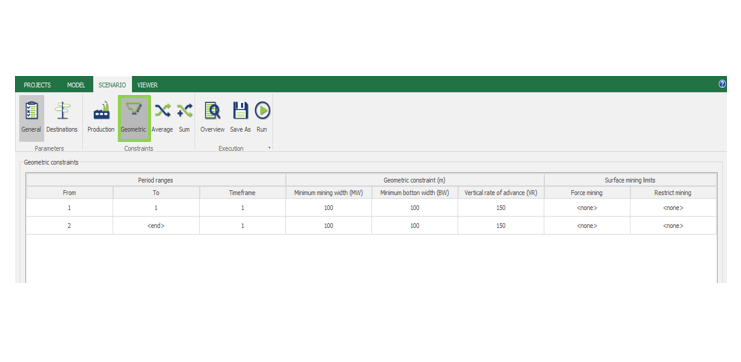

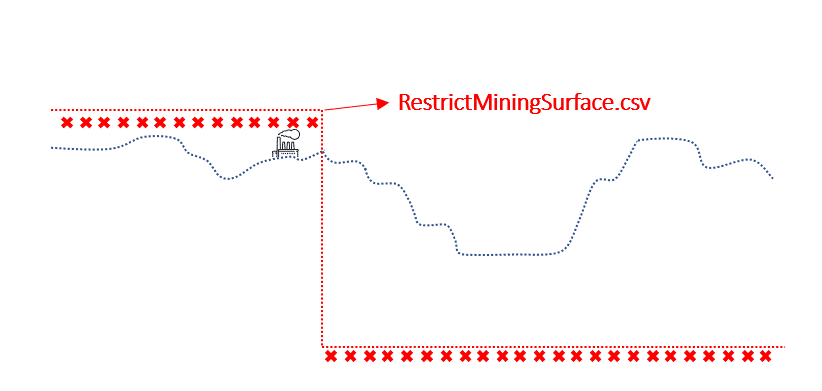

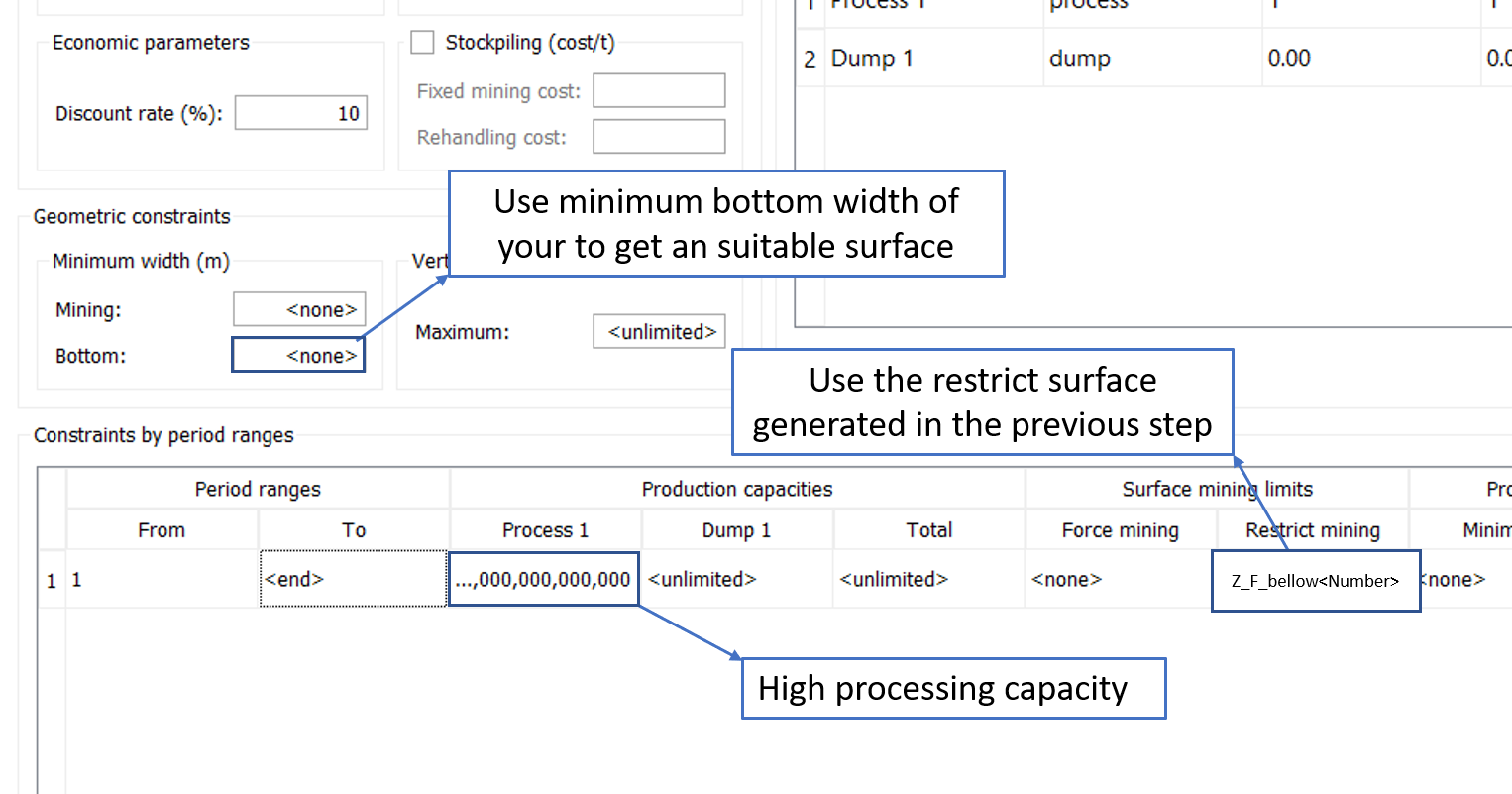

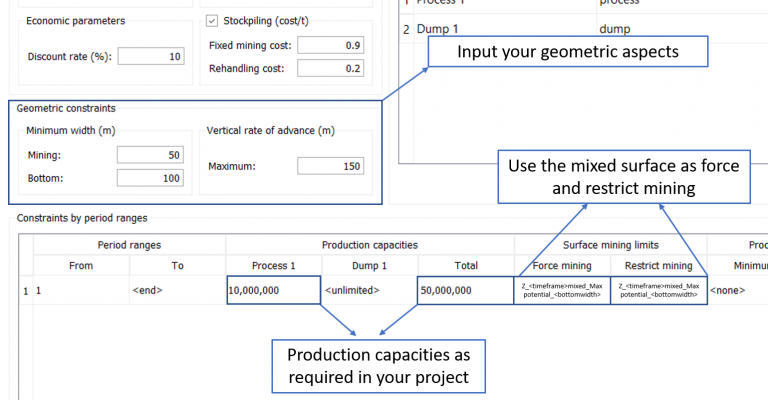

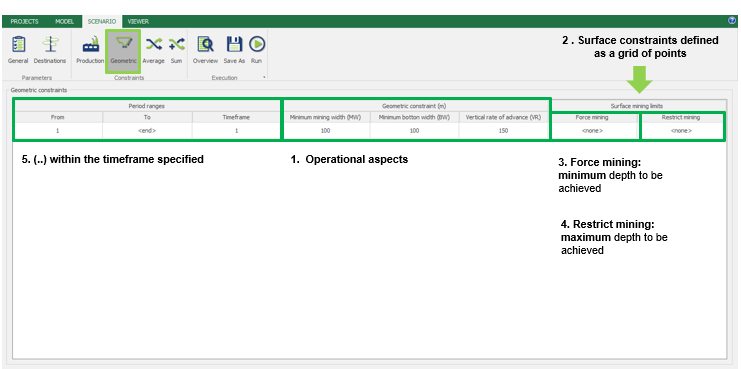

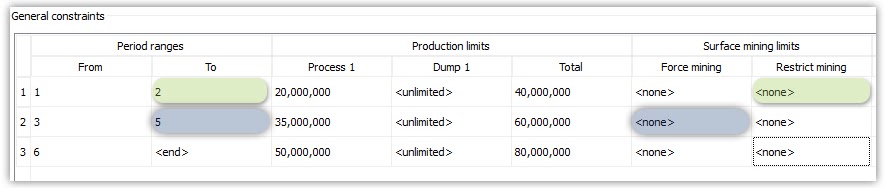

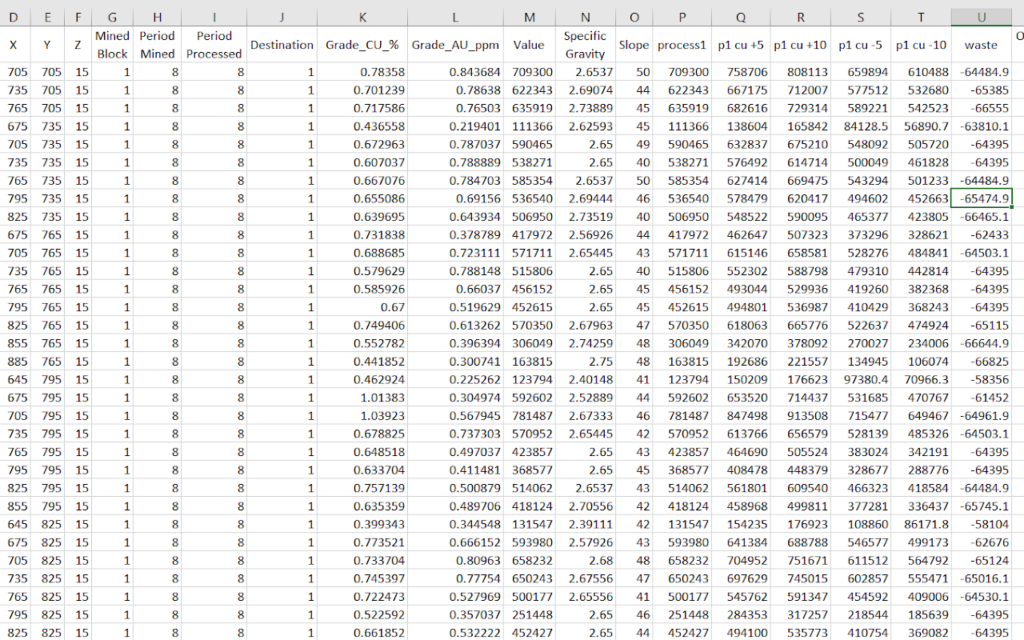

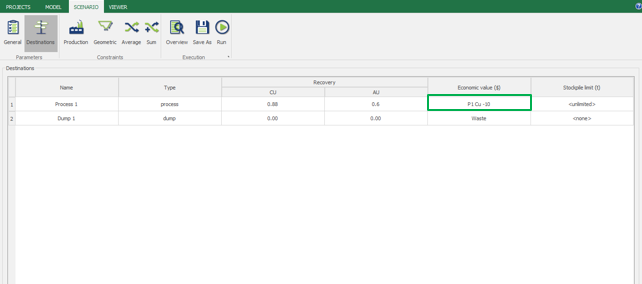

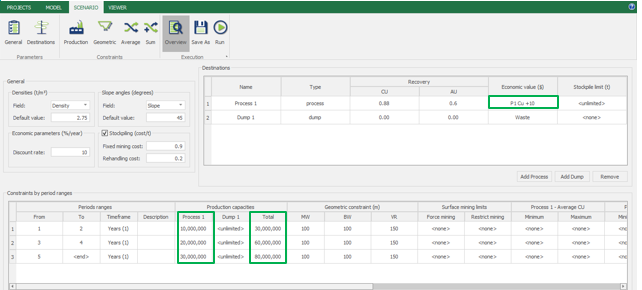

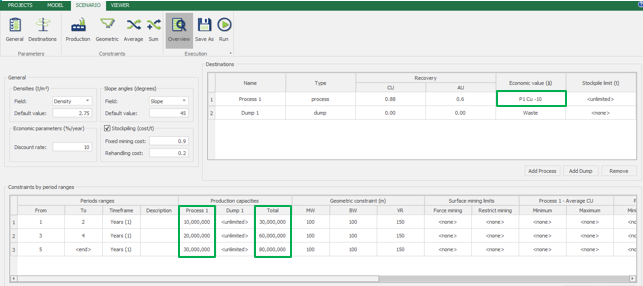

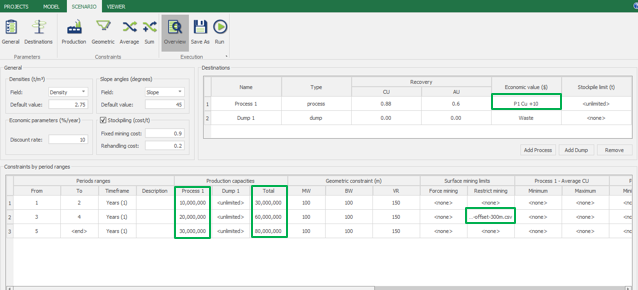

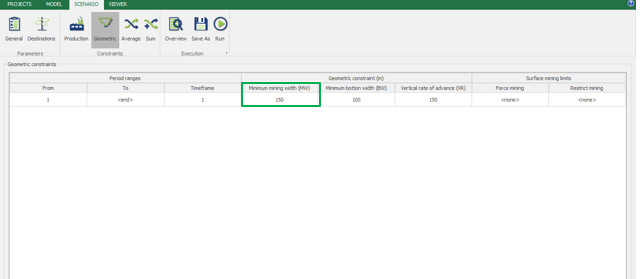

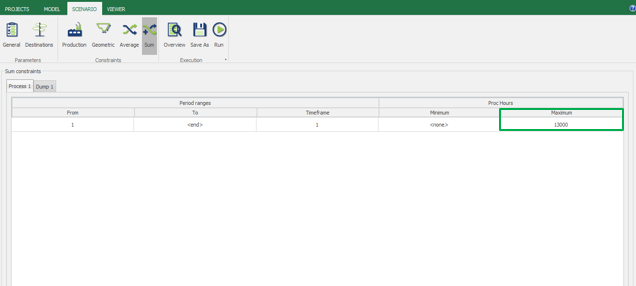

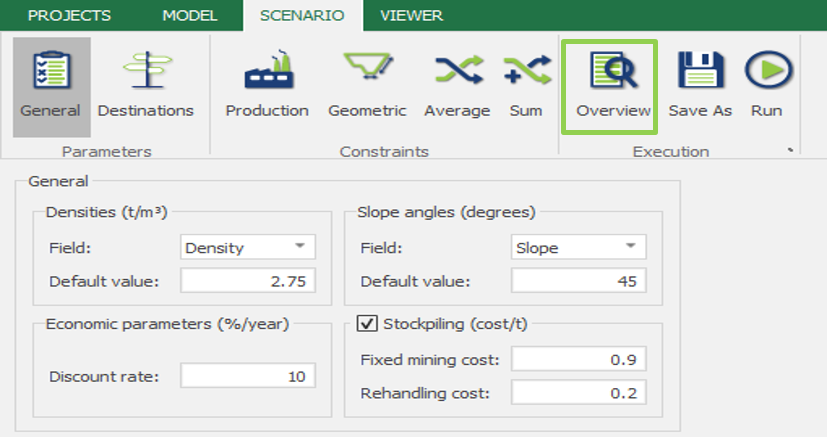

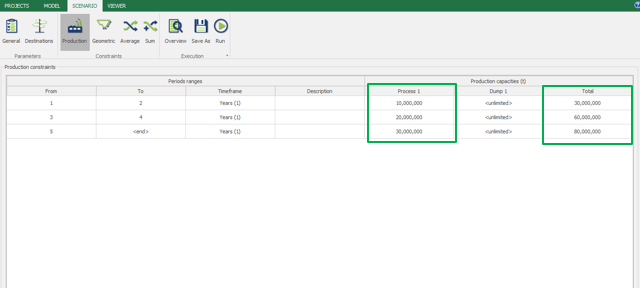

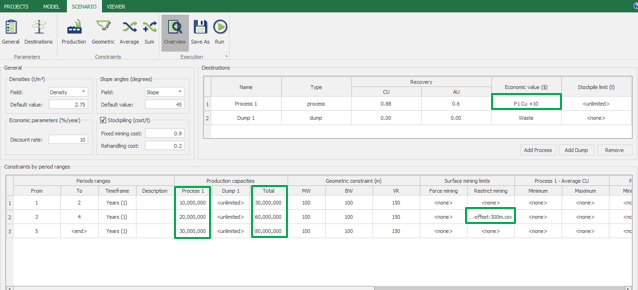

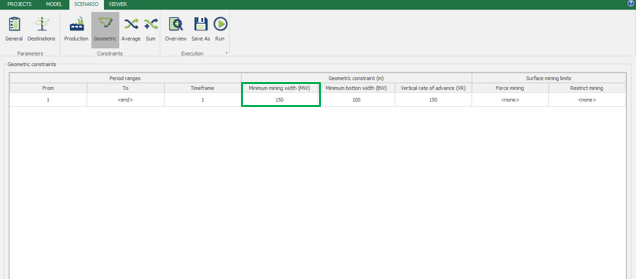

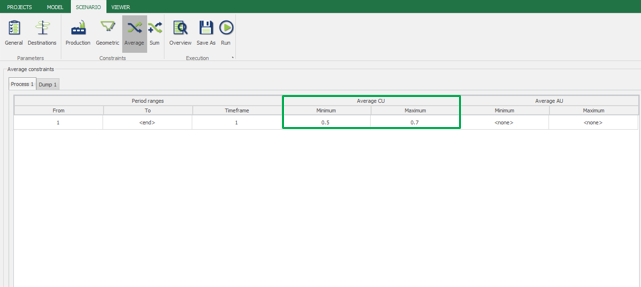

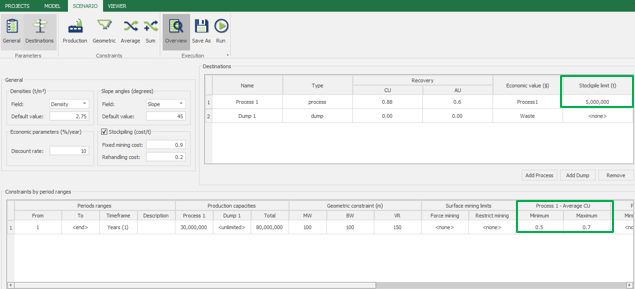

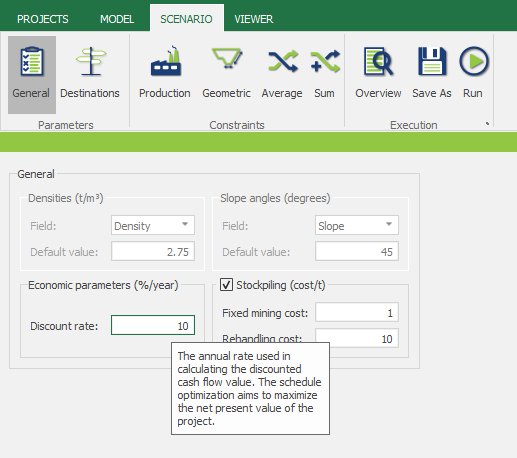

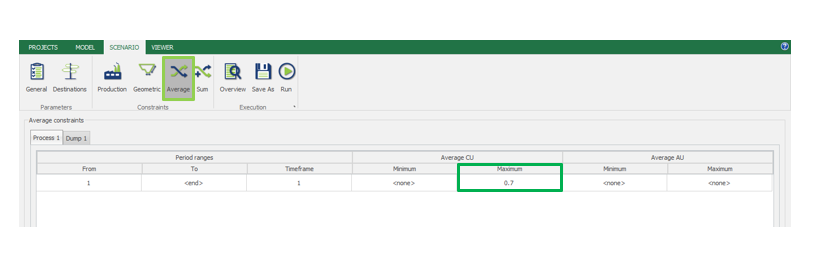

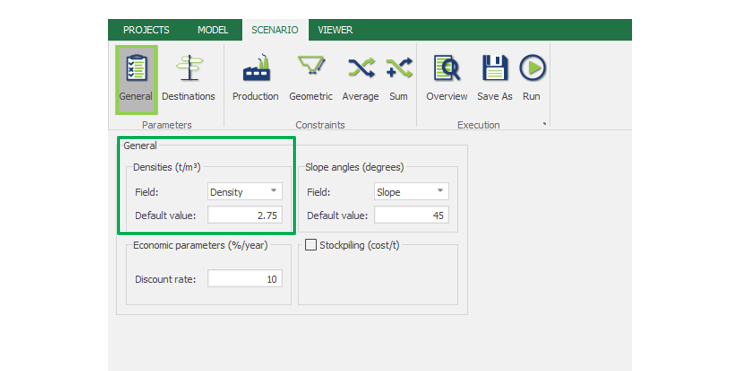

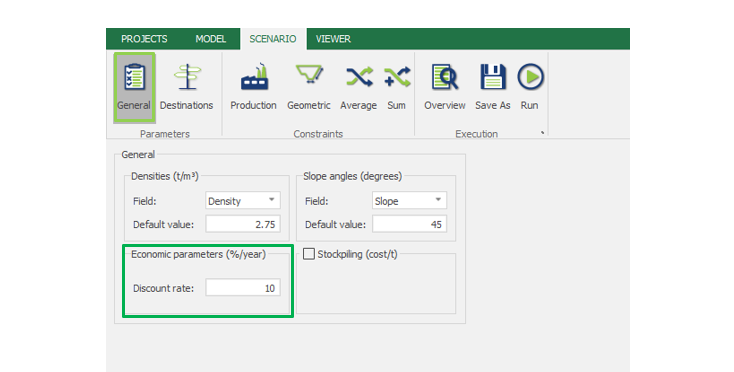

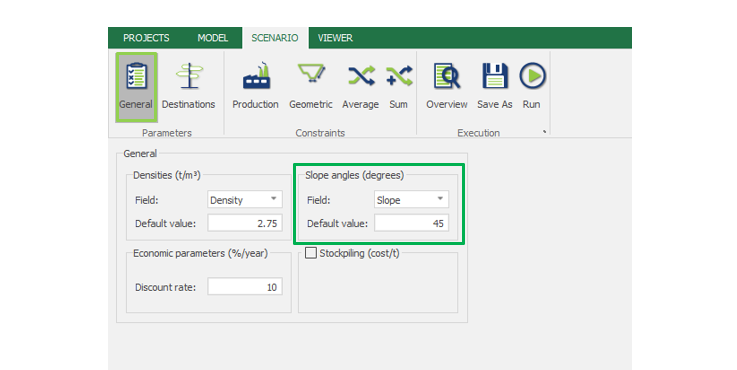

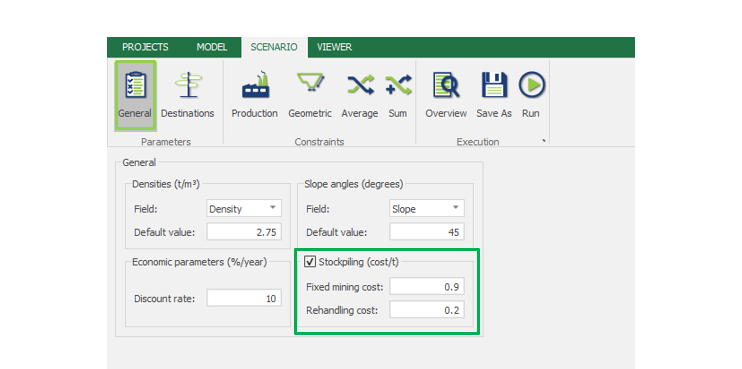

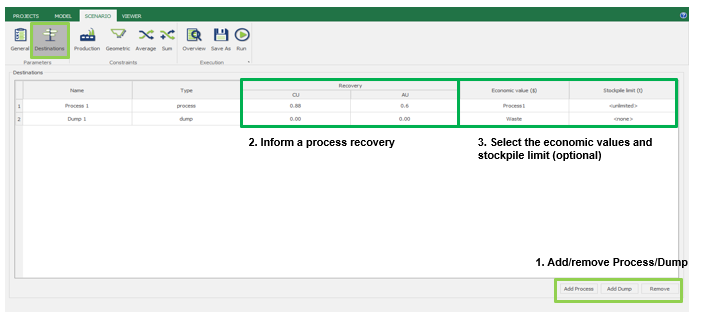

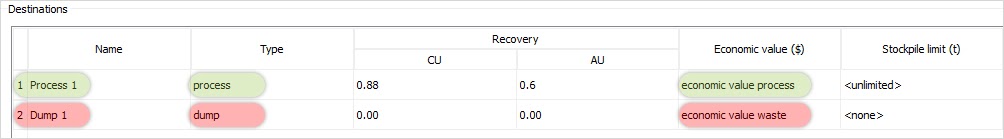

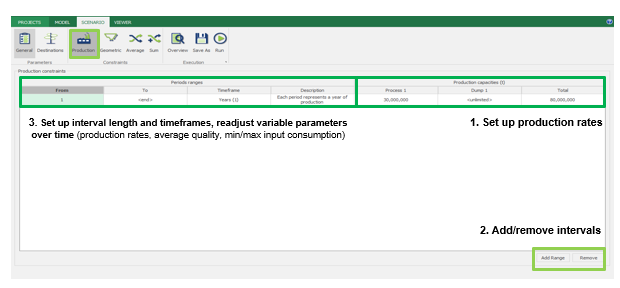

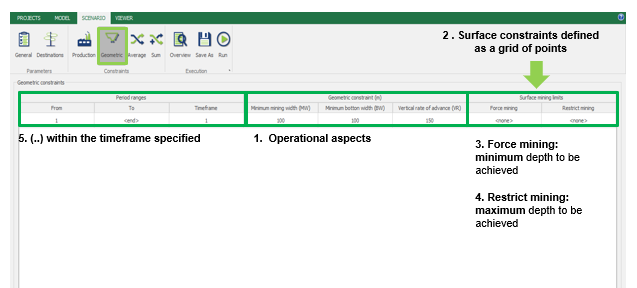

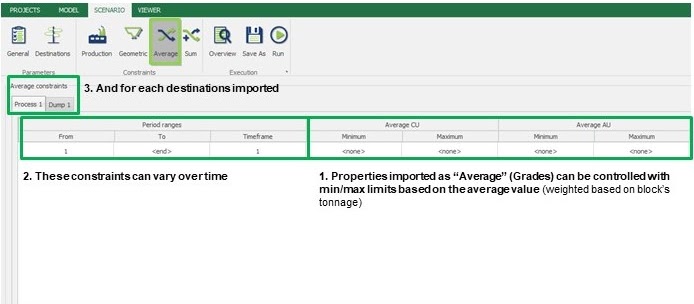

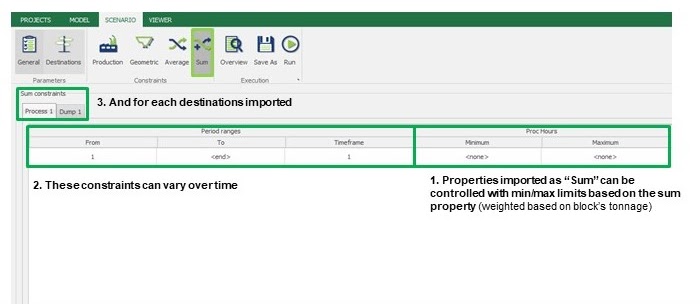

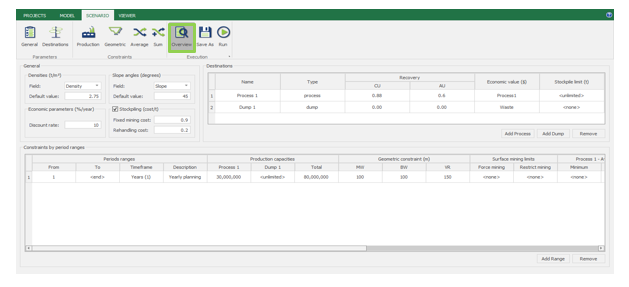

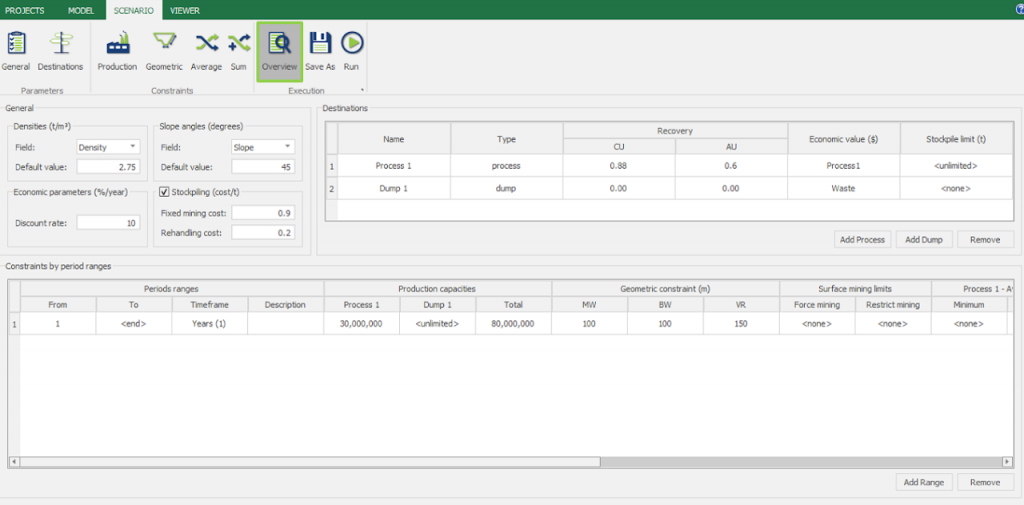

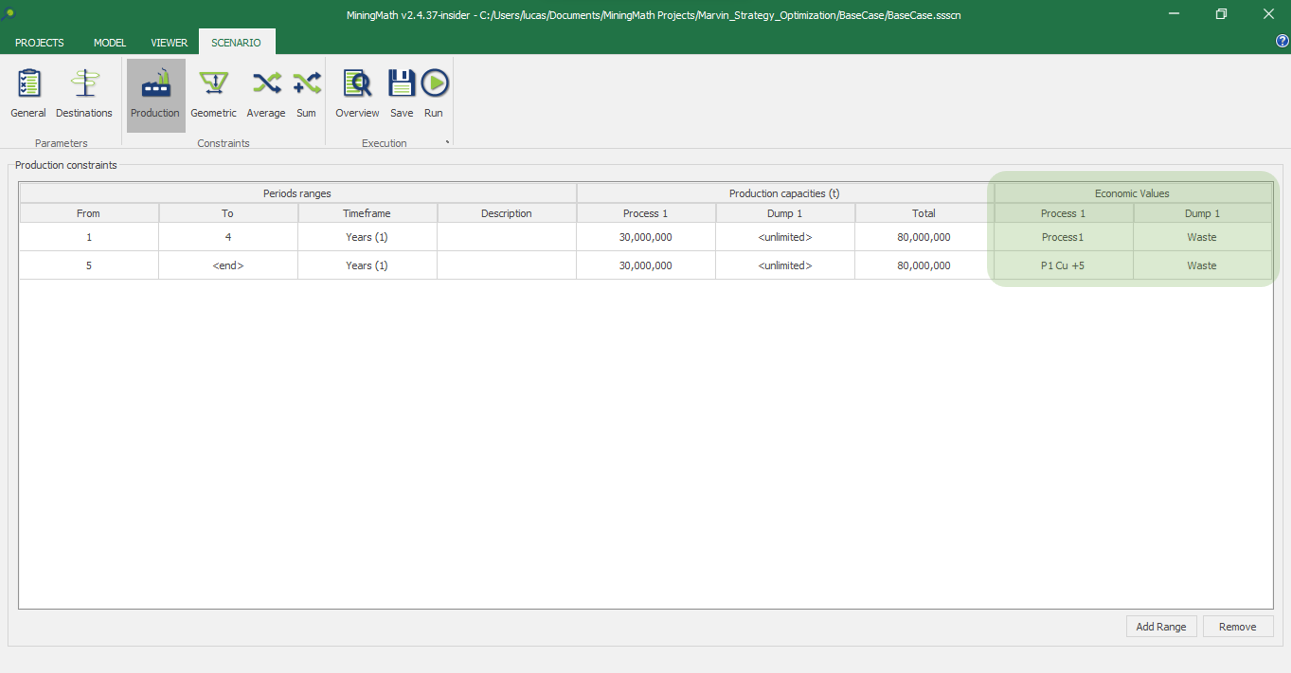

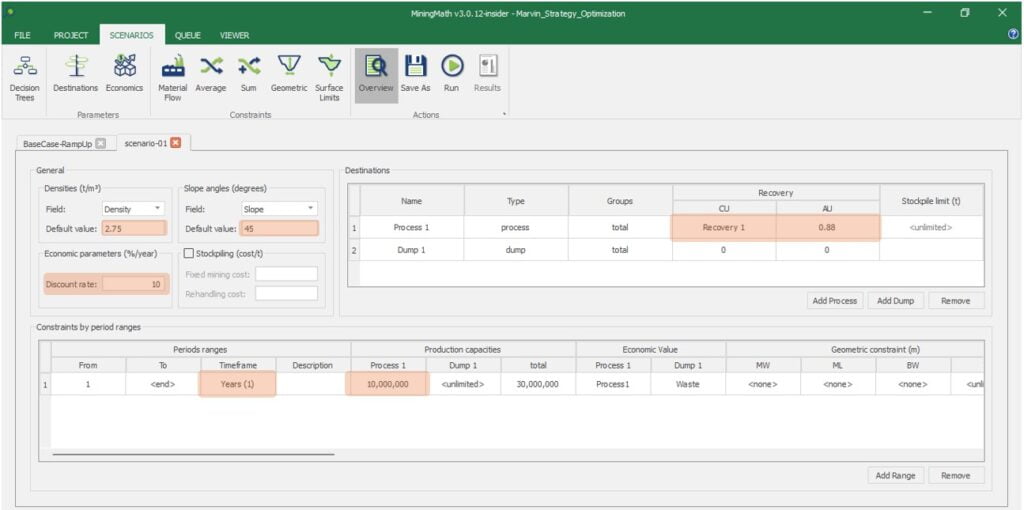

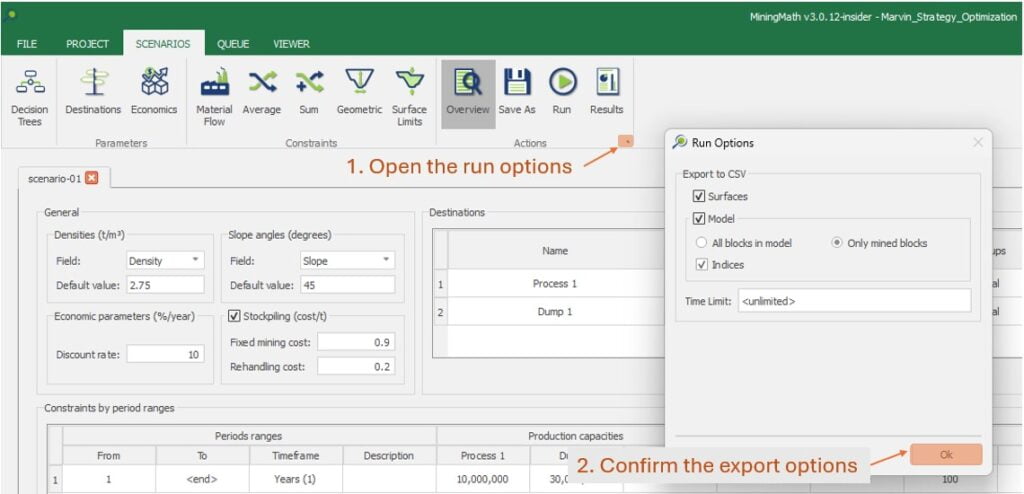

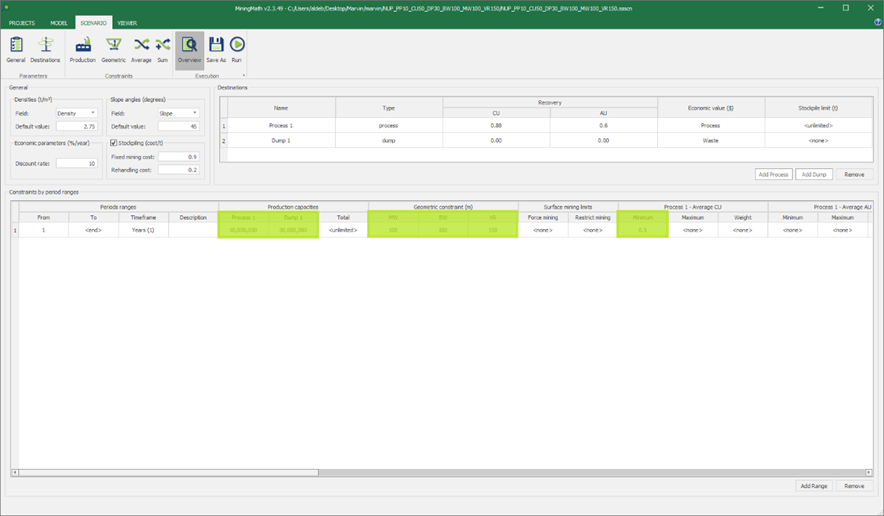

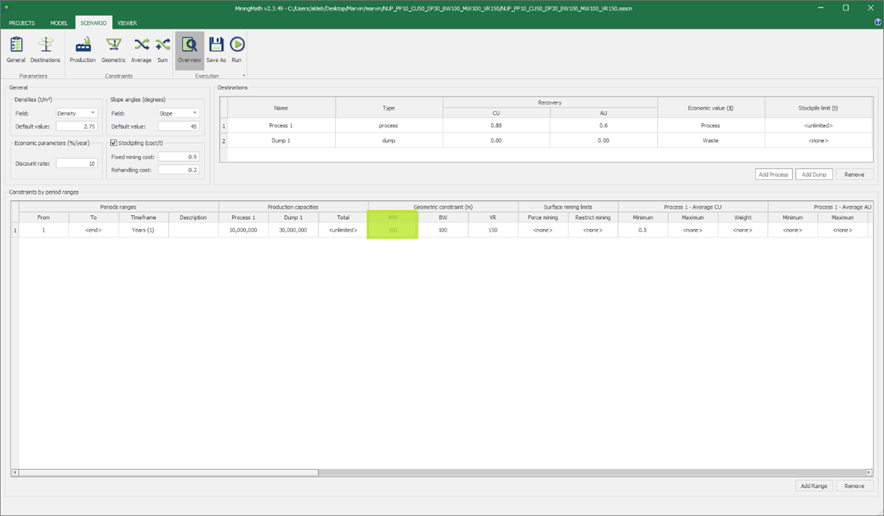

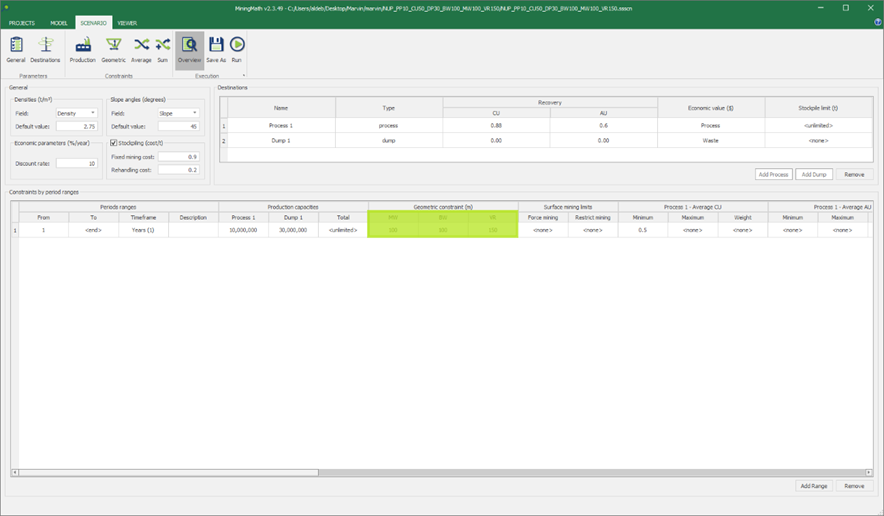

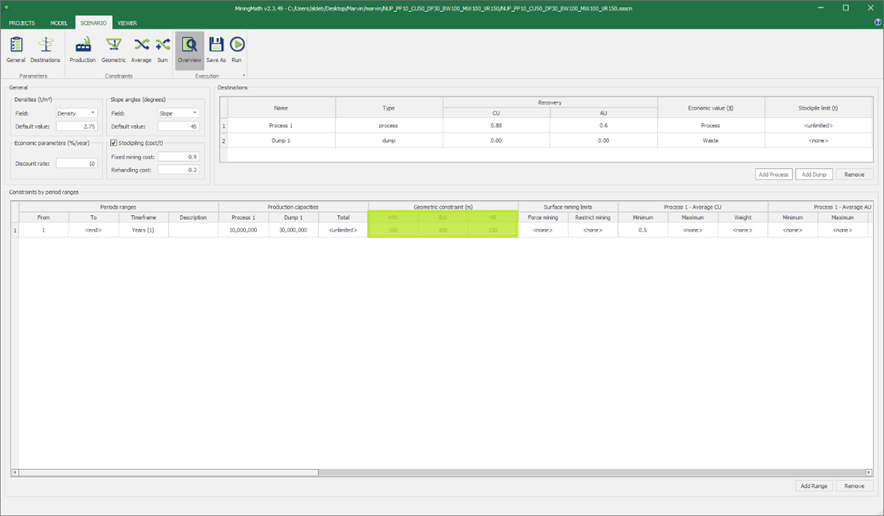

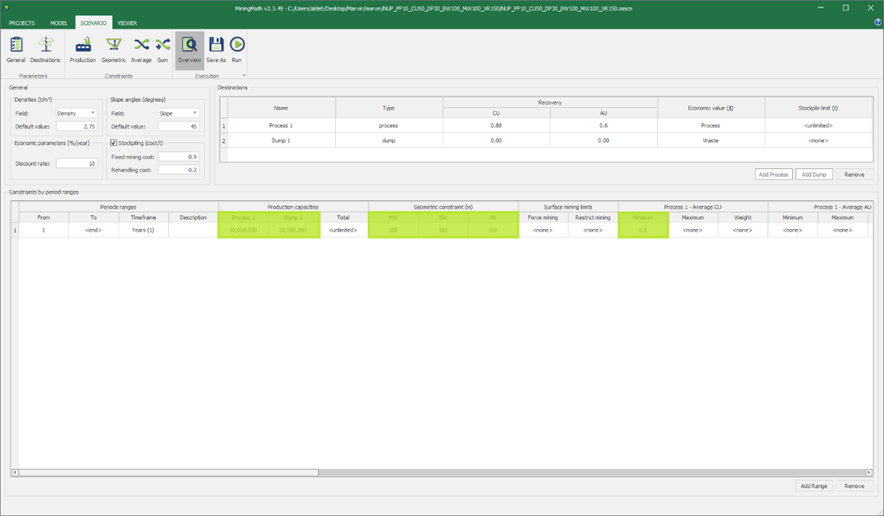

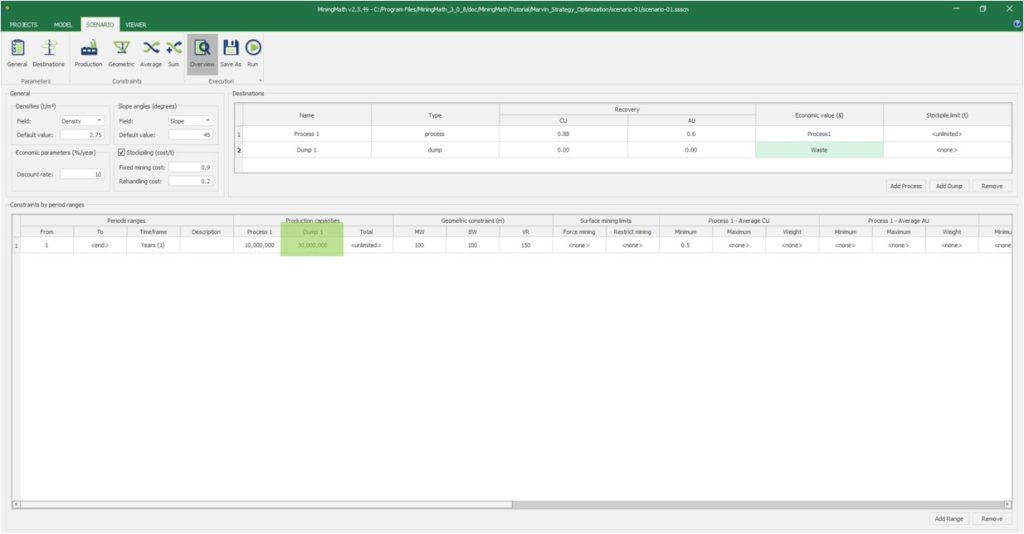

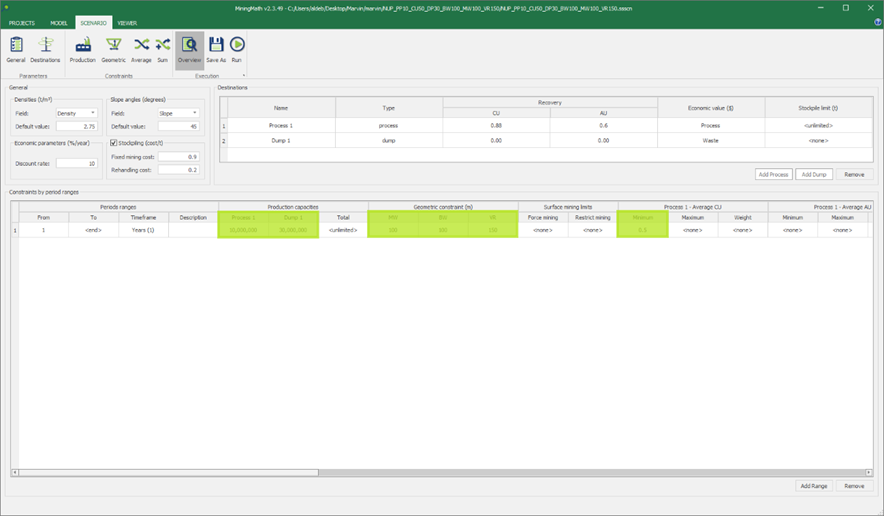

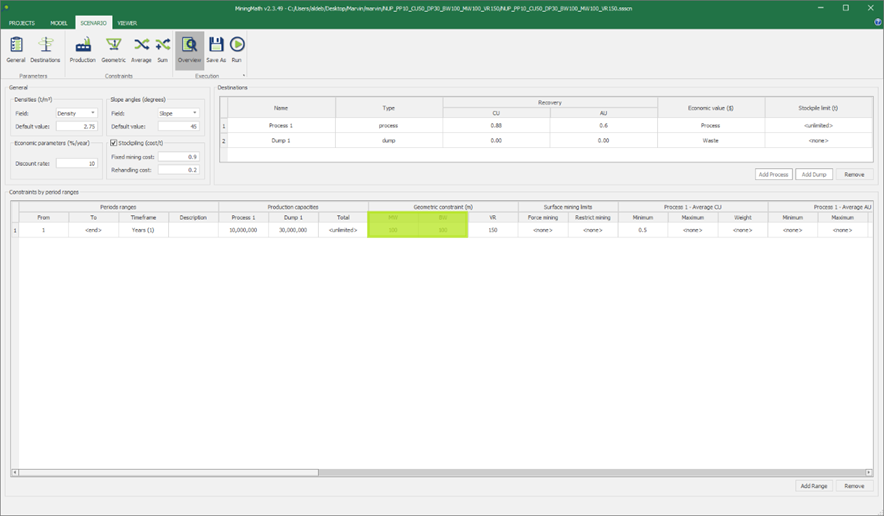

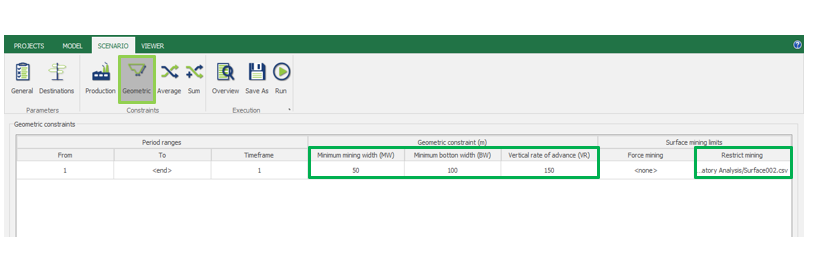

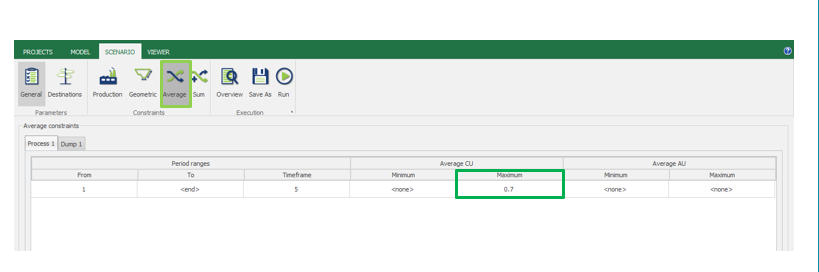

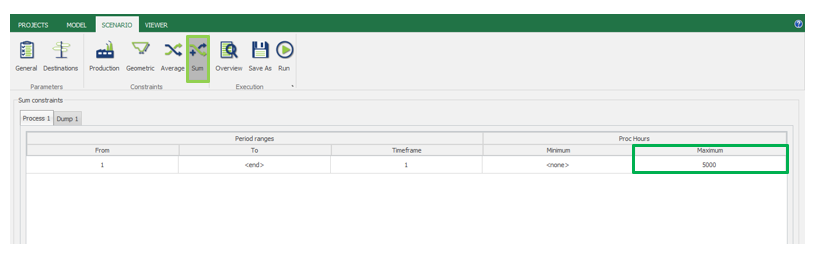

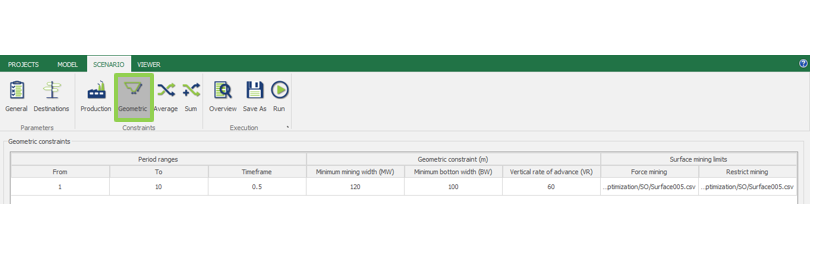

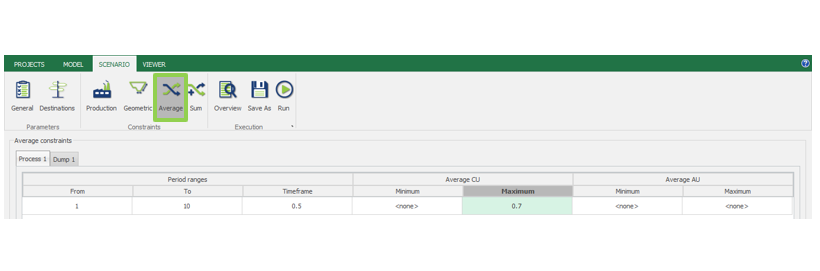

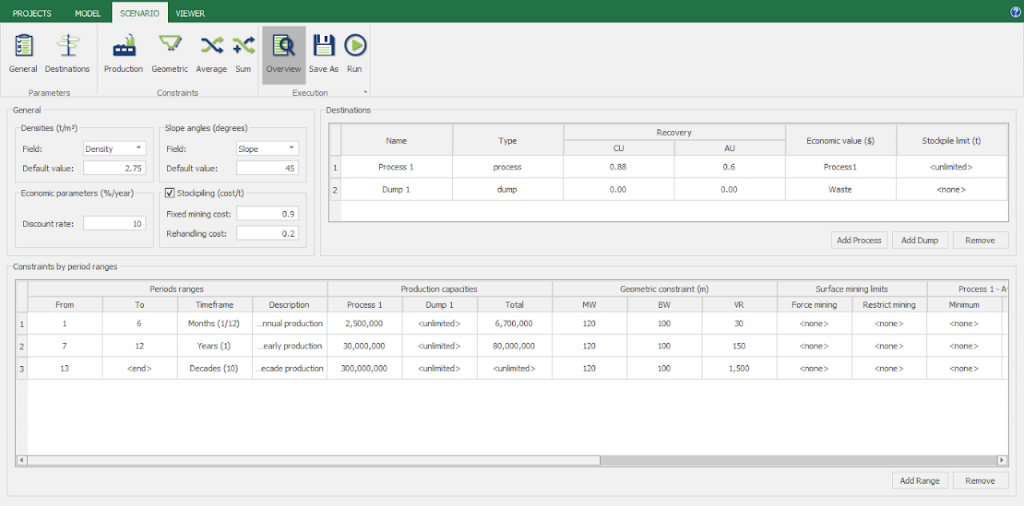

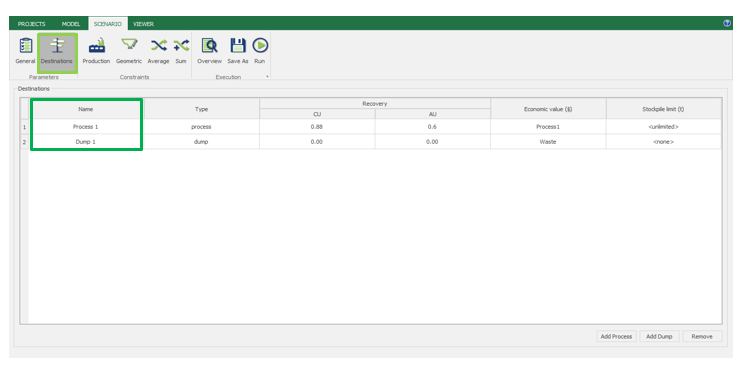

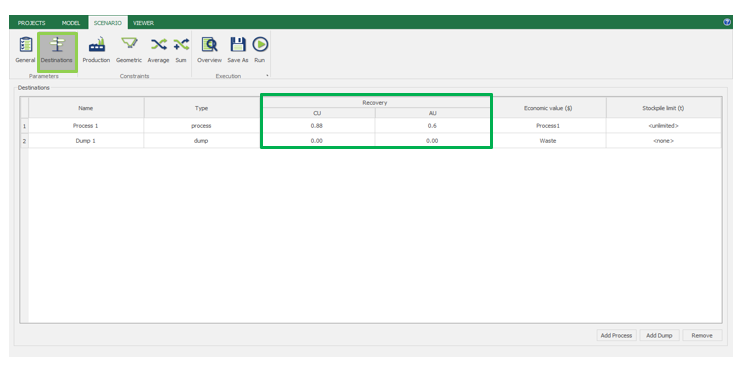

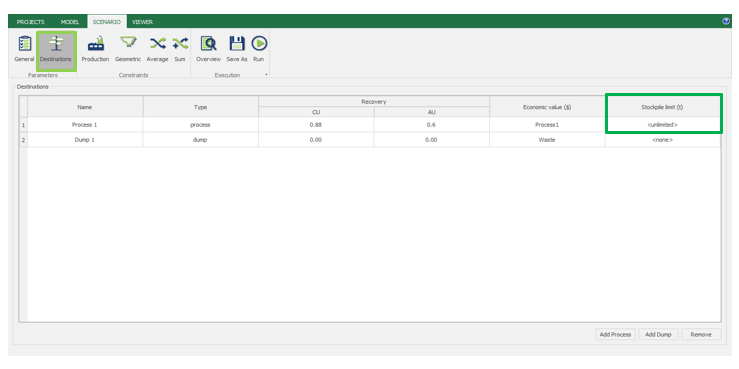

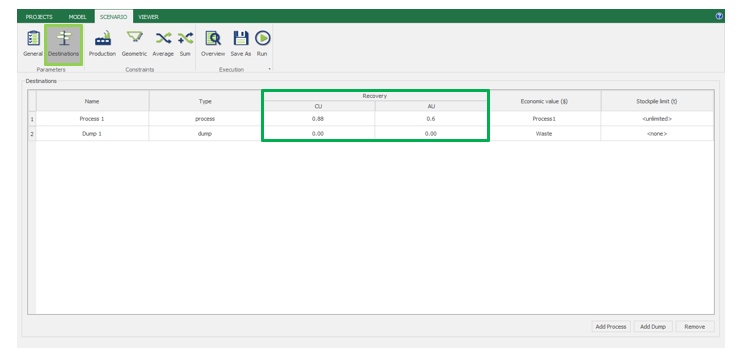

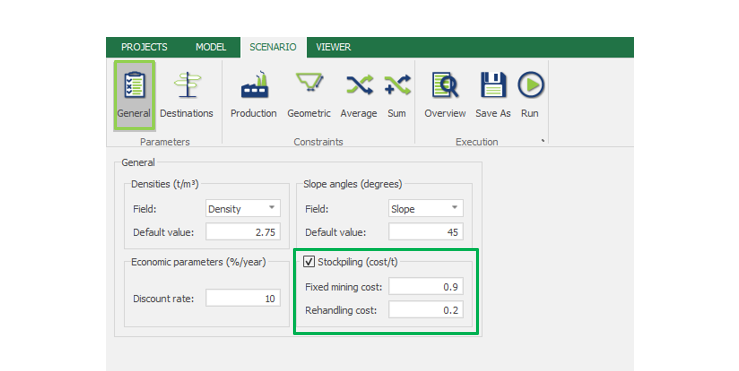

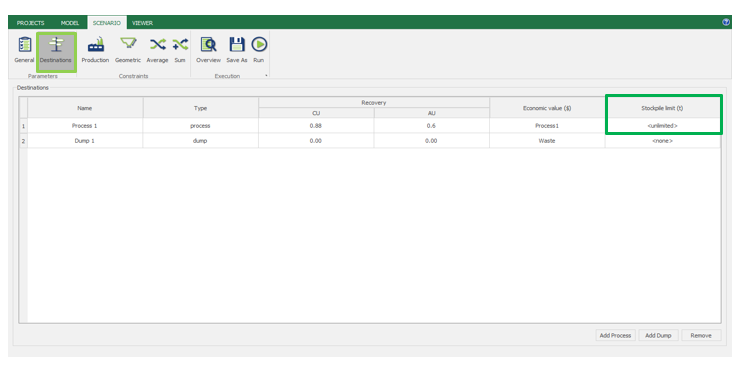

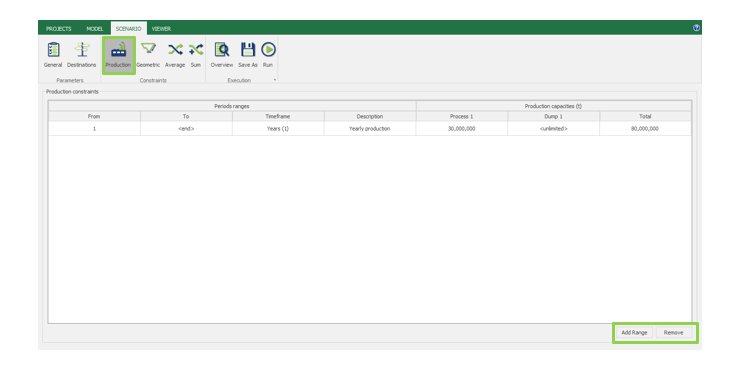

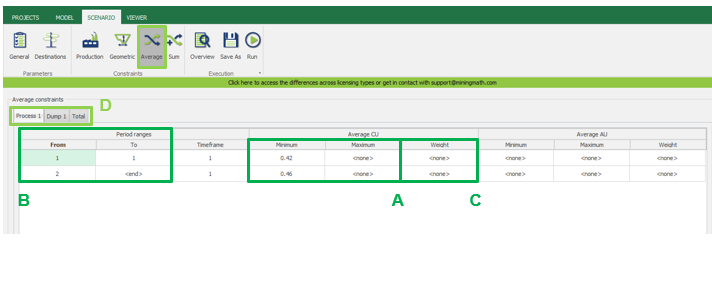

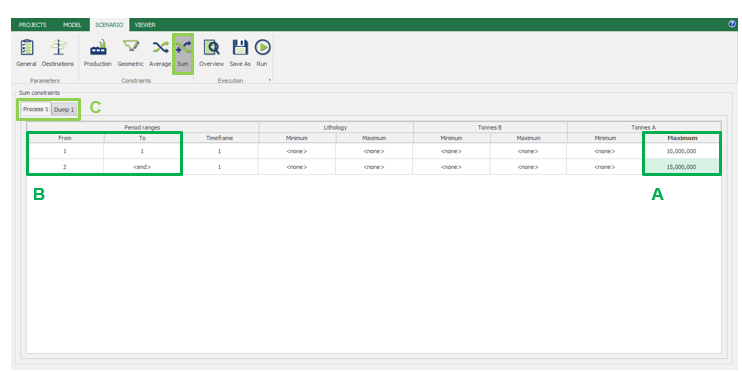

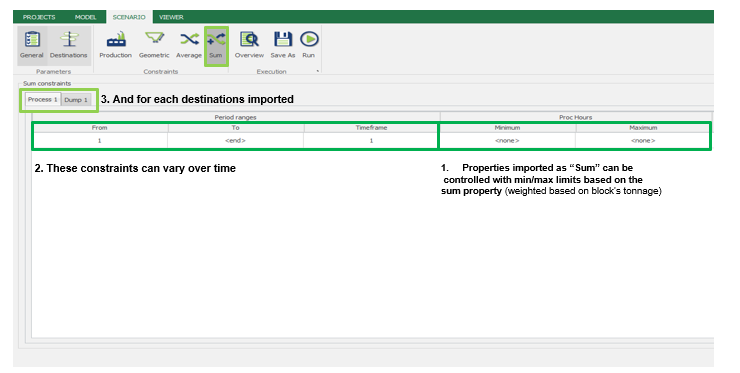

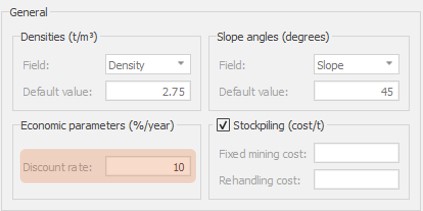

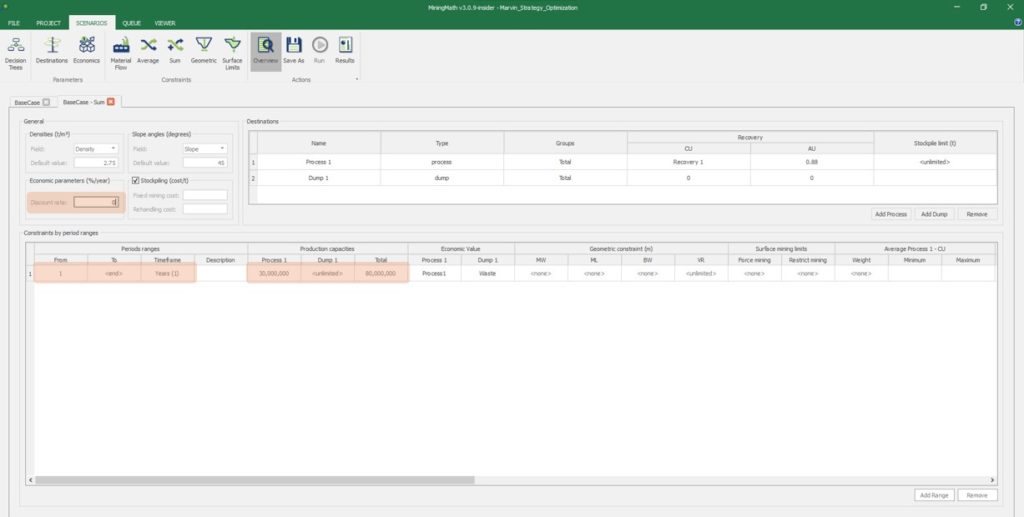

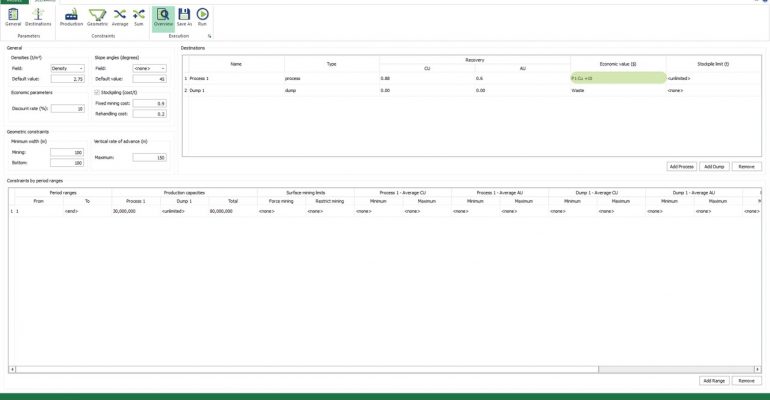

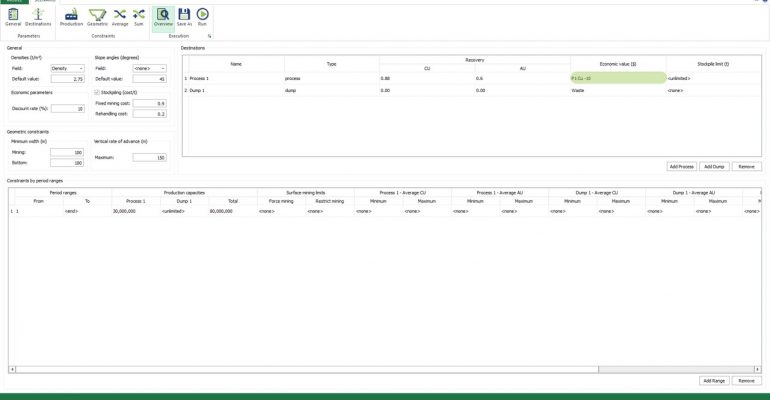

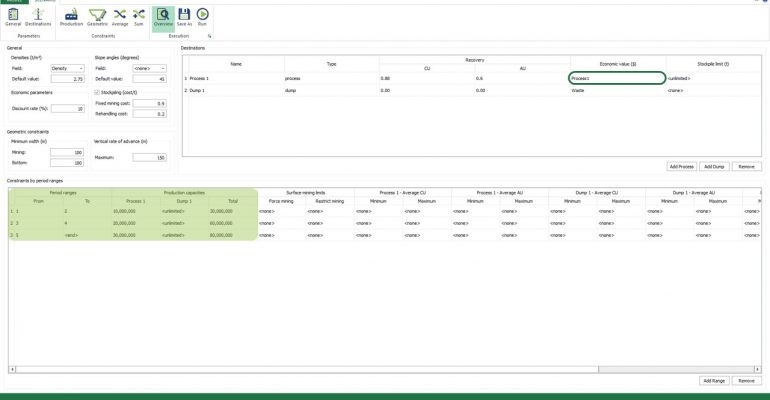

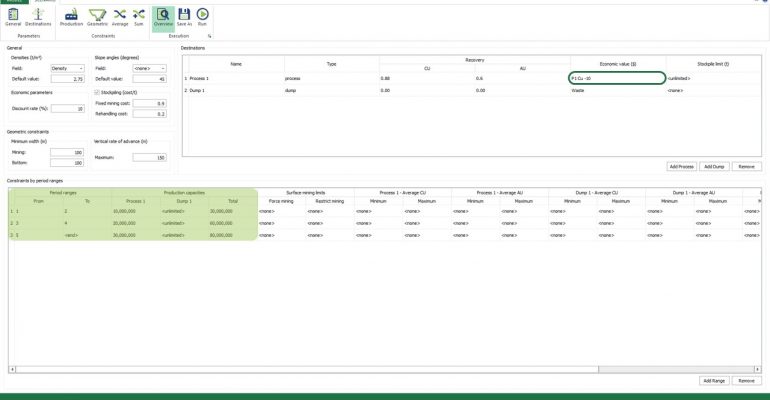

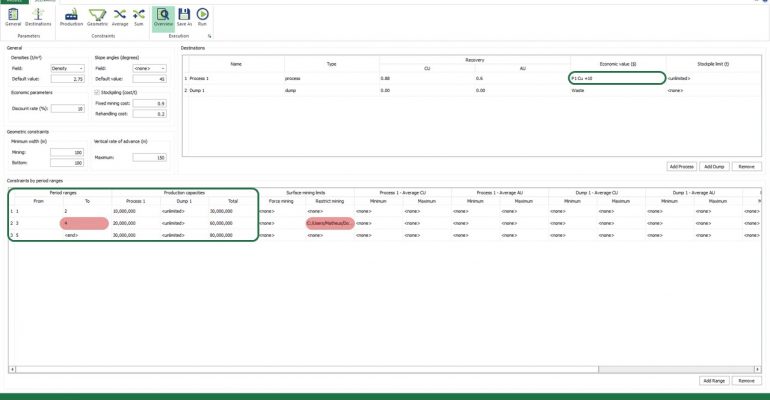

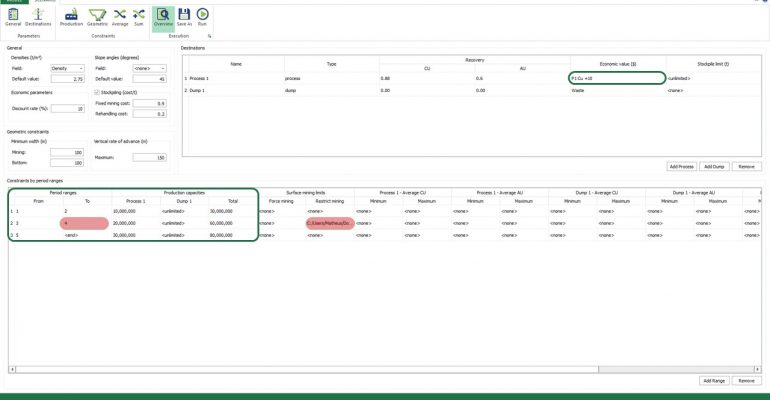

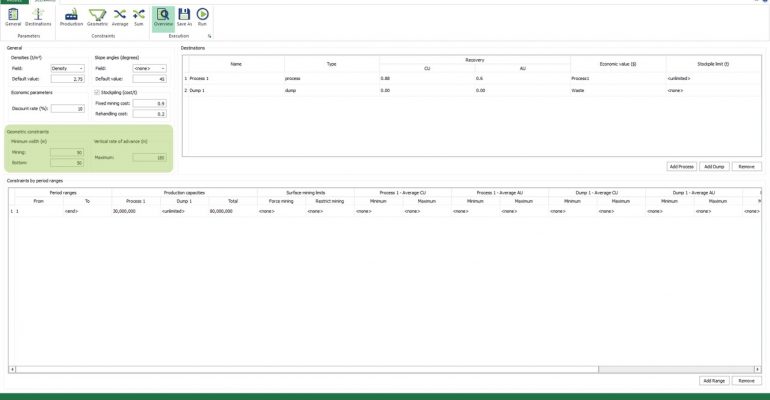

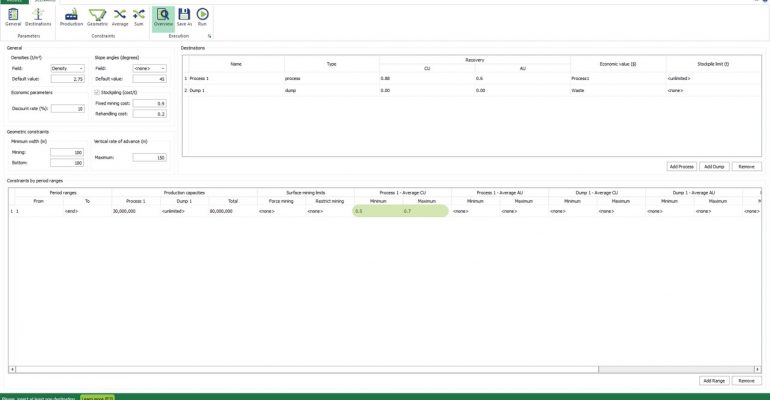

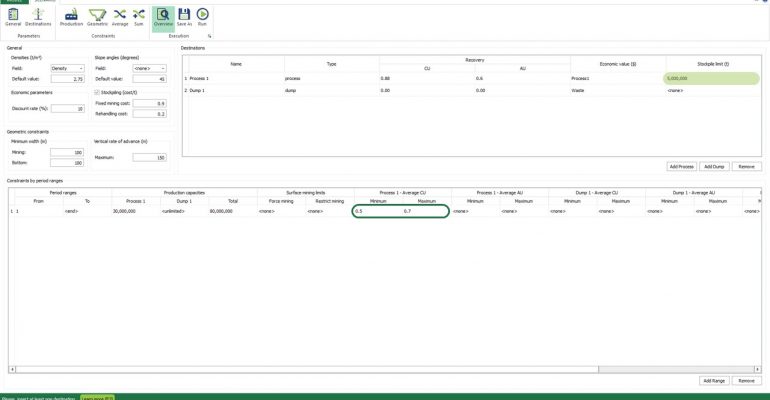

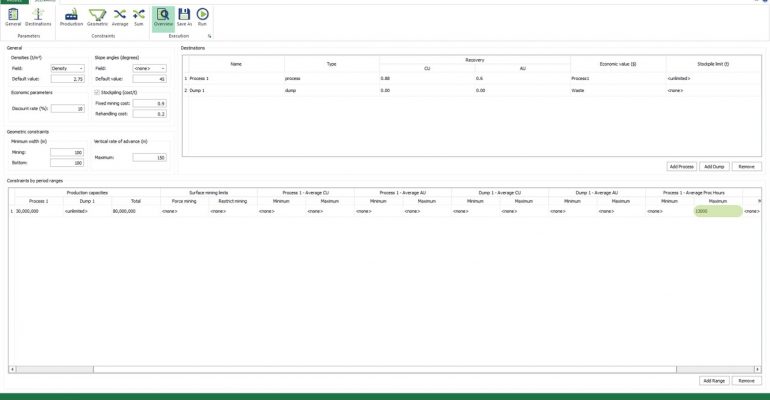

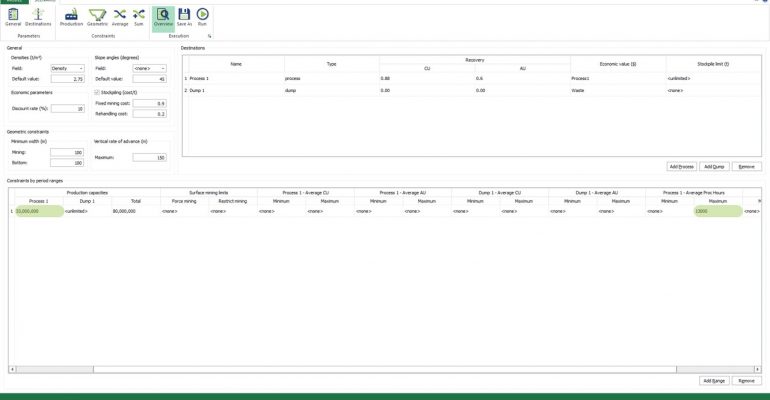

Scenario tab: set densities, economic parameters, slope angles, stockpiles, add/remove processes and dumps, production inputs, geometric inputs and so on.

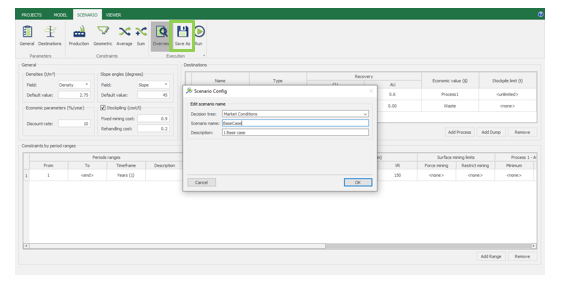

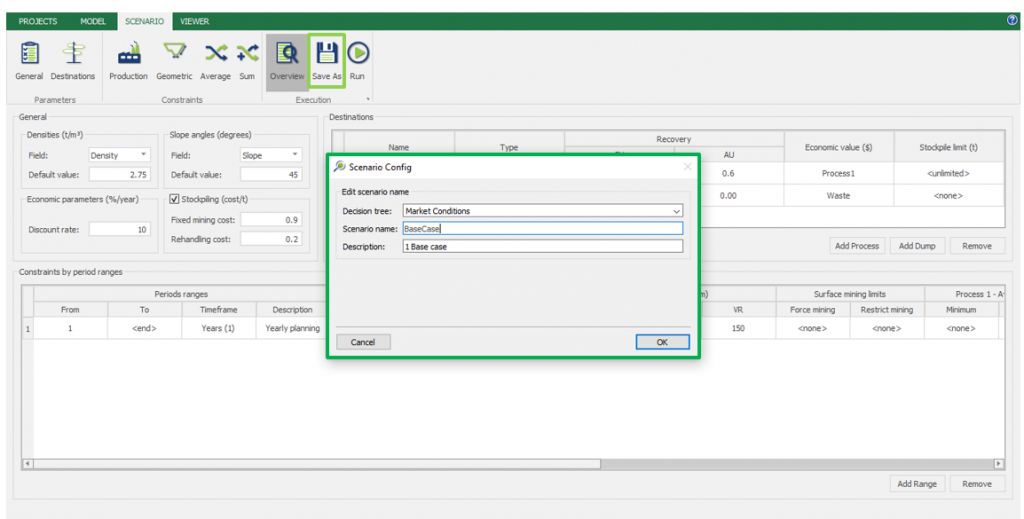

Save as: save the scenario's configuration once it has been configured.

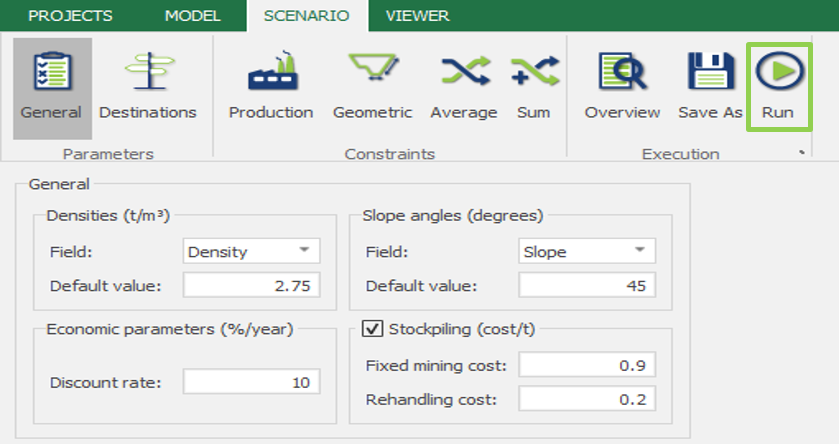

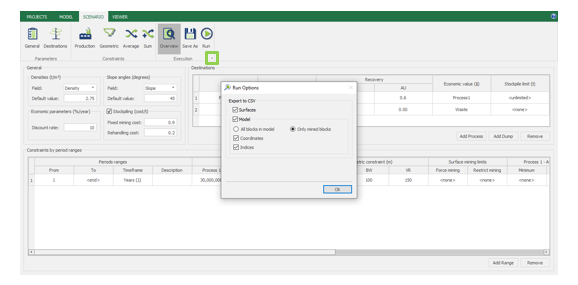

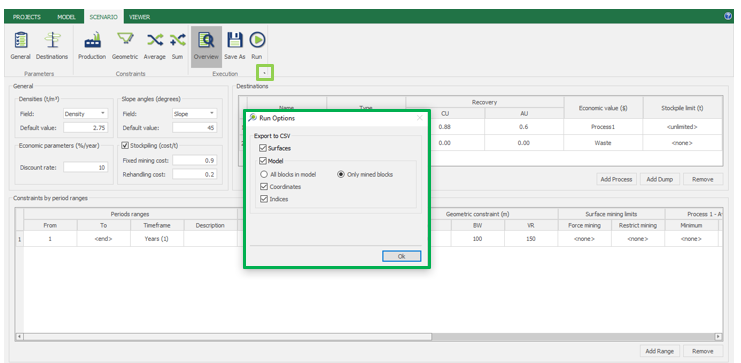

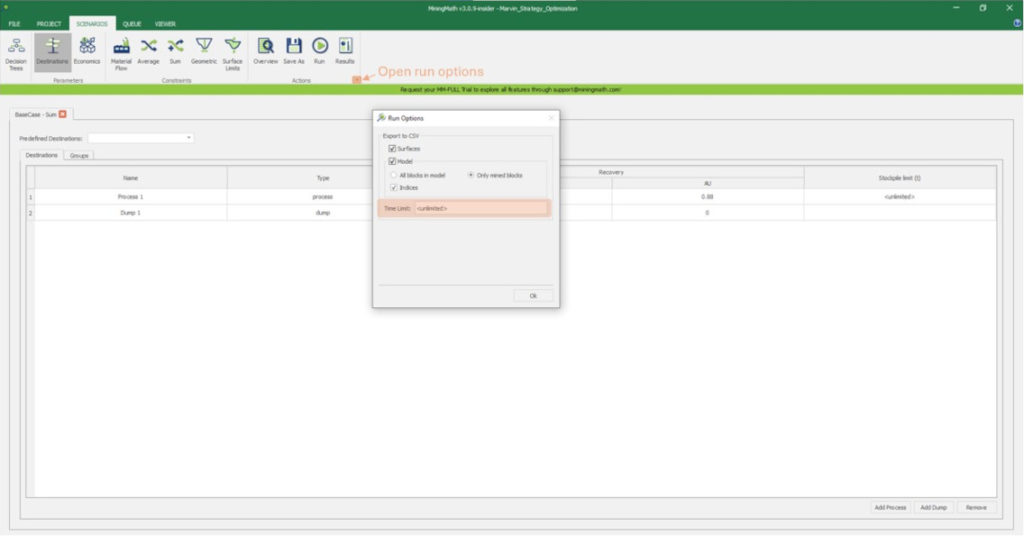

Run: the Run tab is the last step before running your project’s optimization. Change the scenario name, set a time limit, and set up results files.

Results

After running your scenario it is important to analyze and understand the given results.

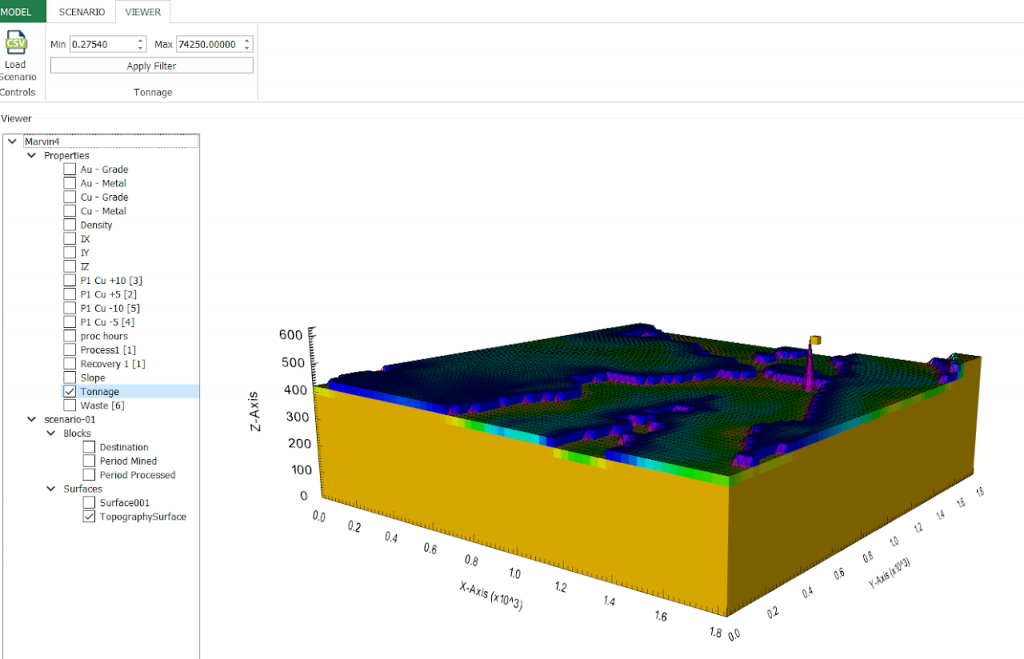

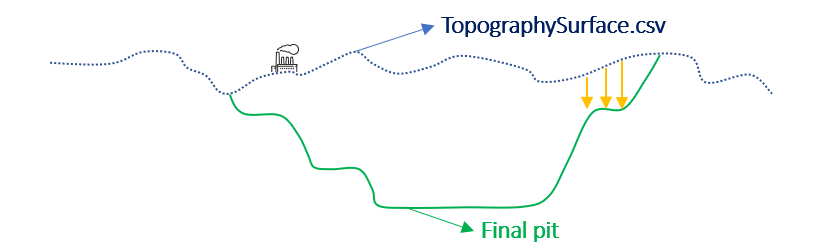

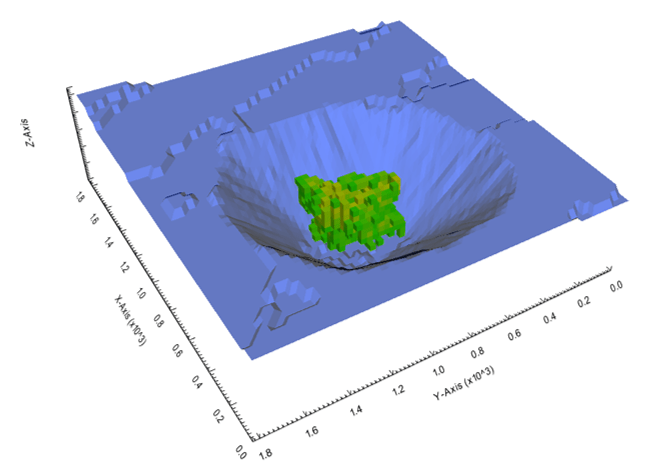

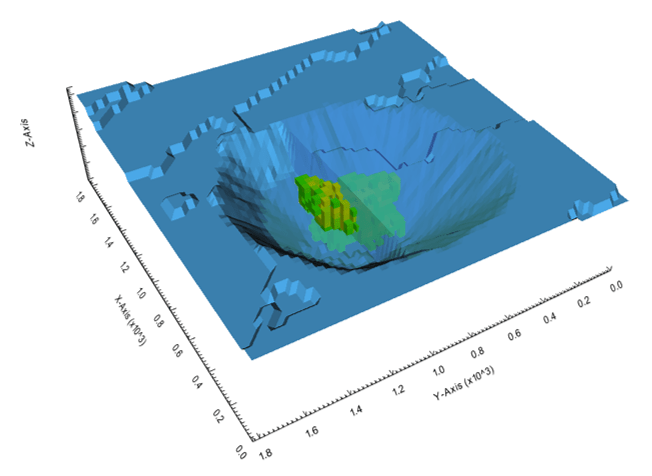

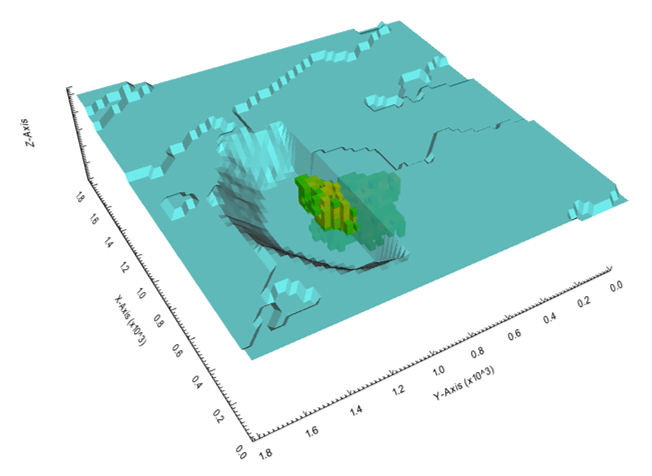

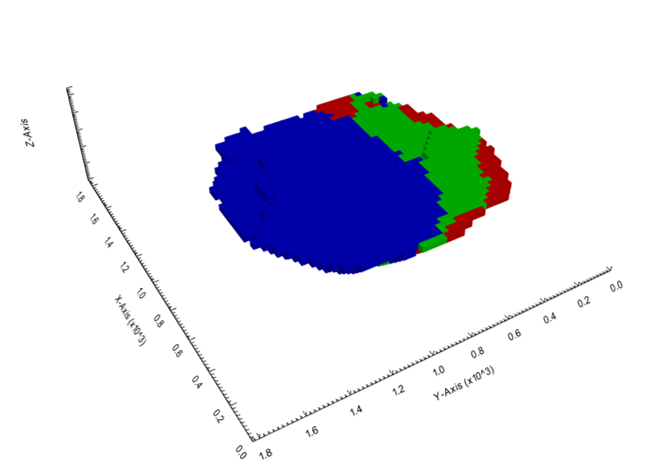

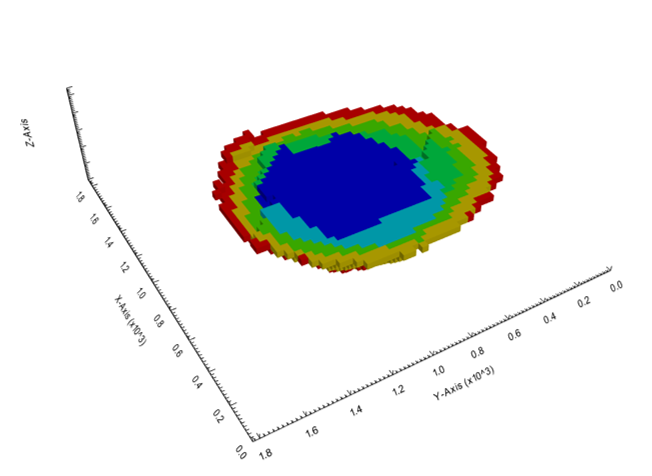

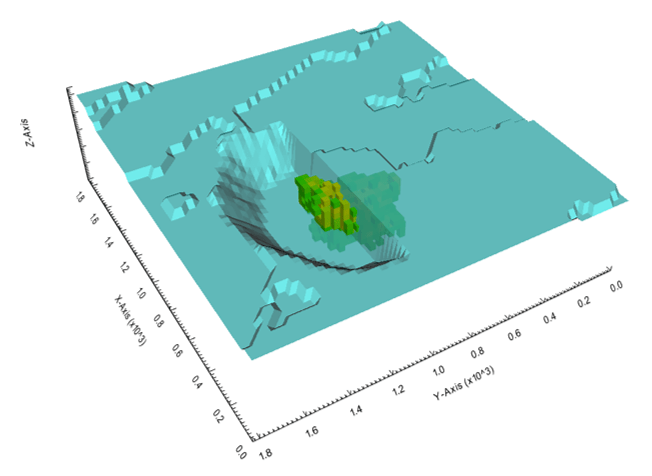

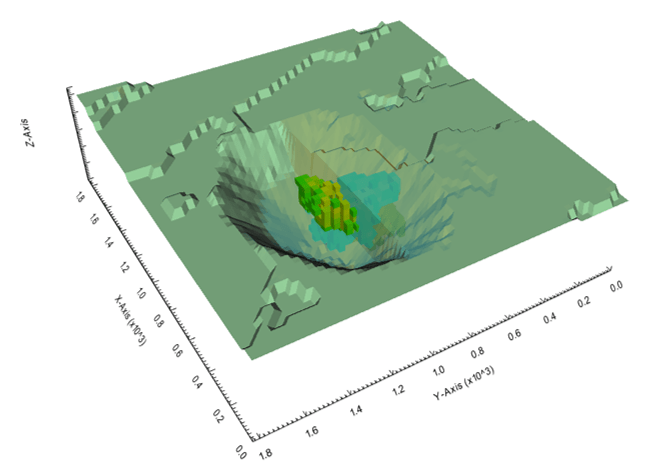

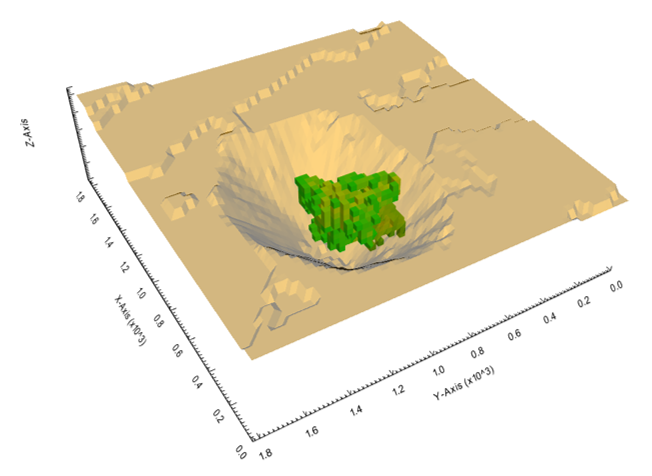

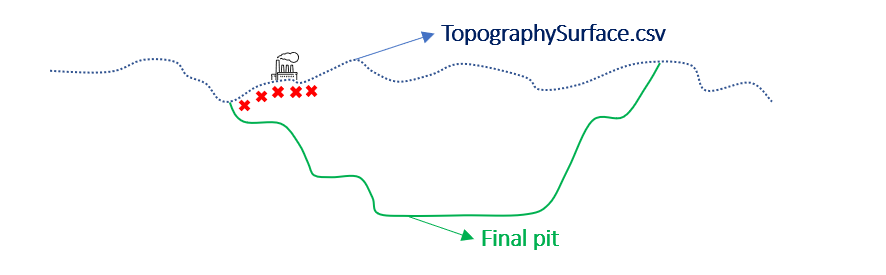

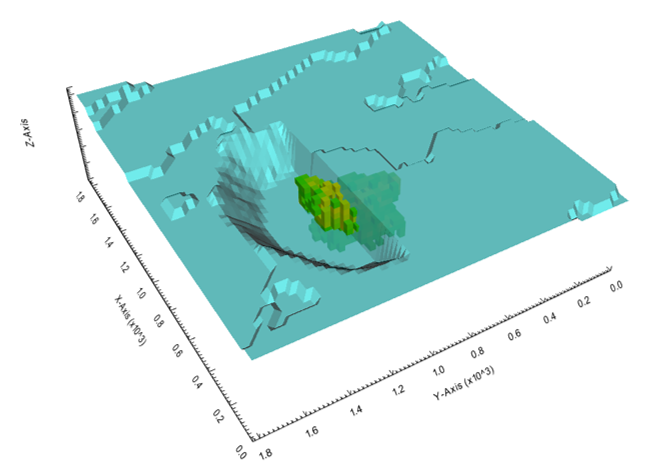

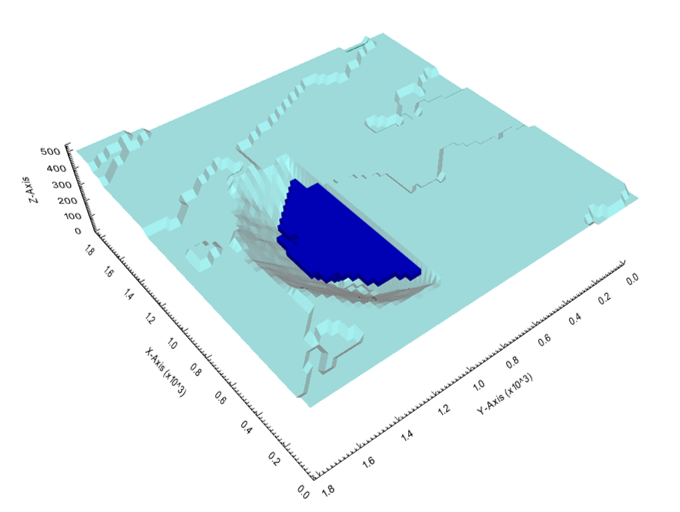

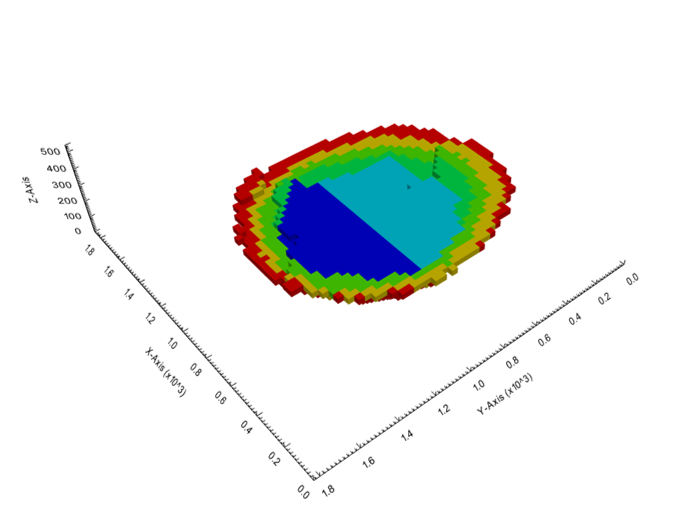

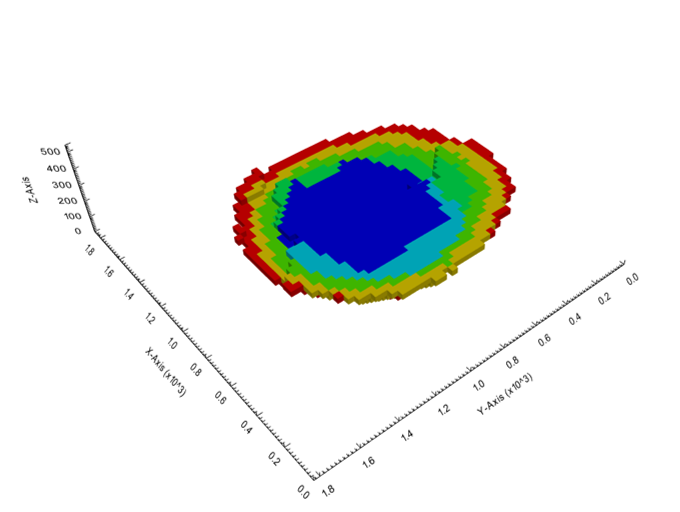

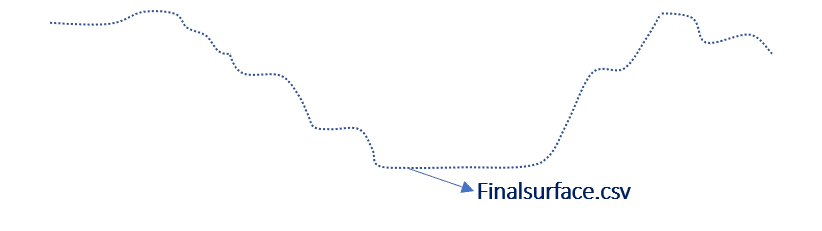

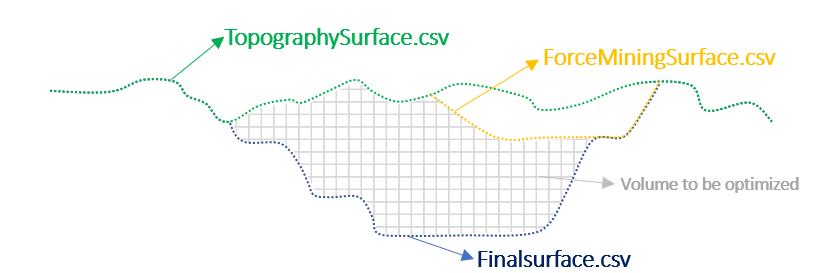

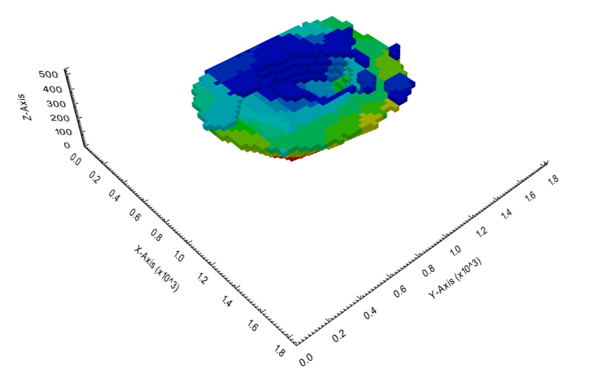

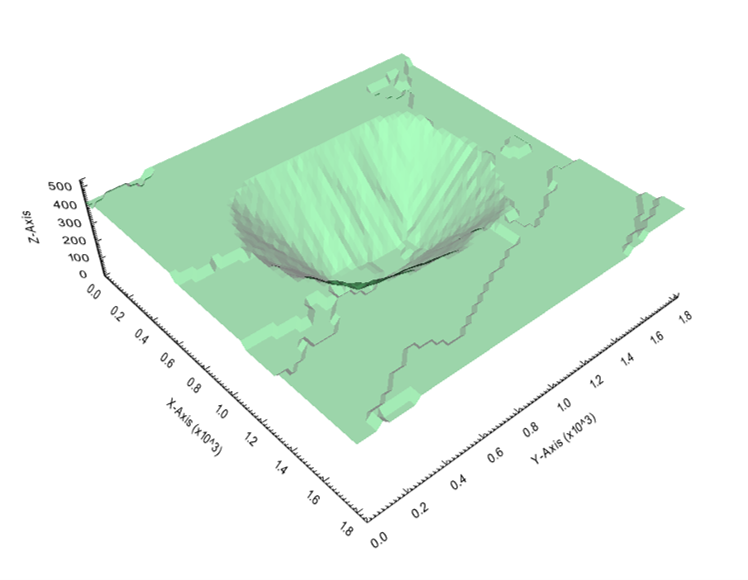

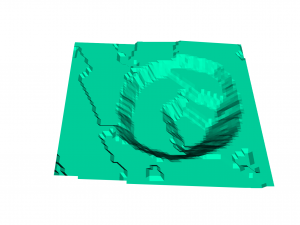

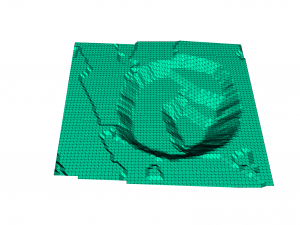

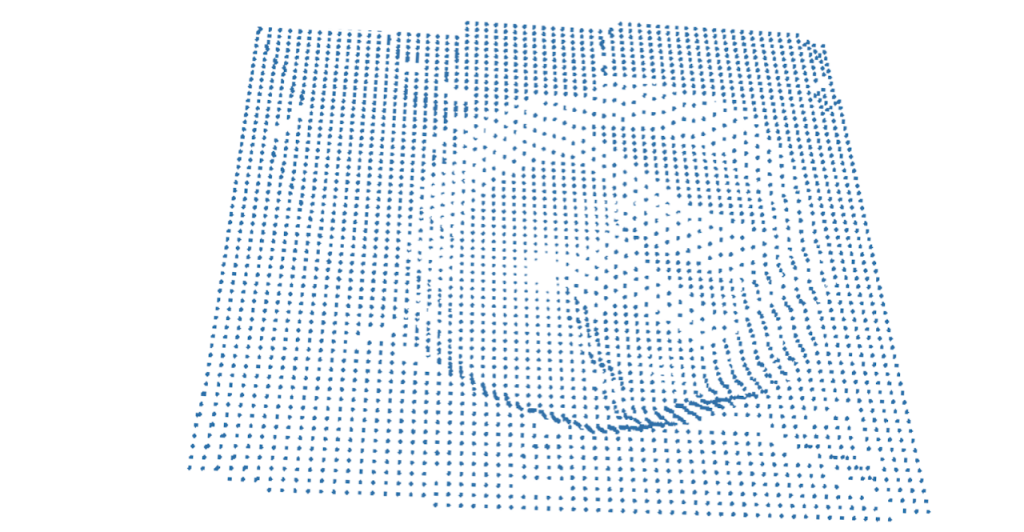

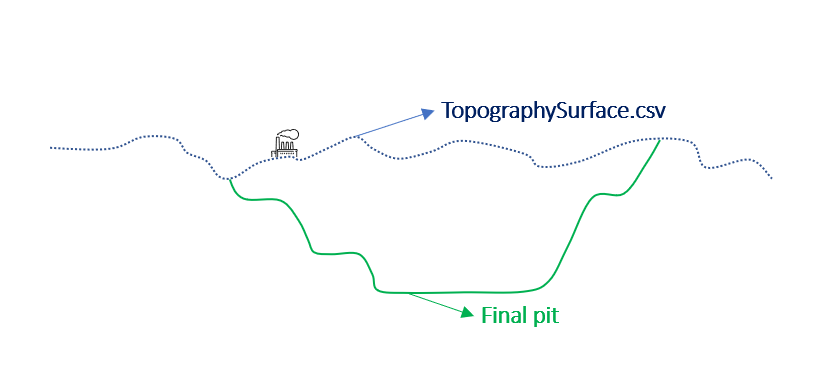

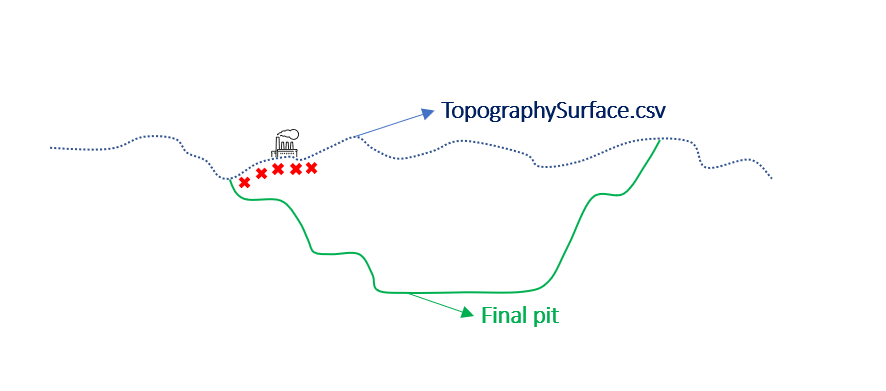

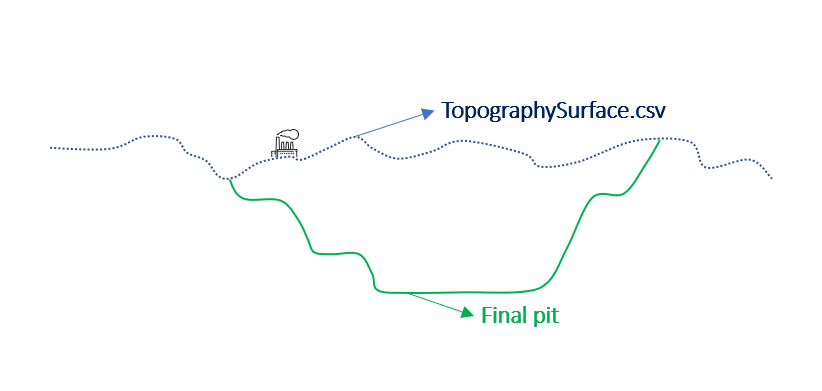

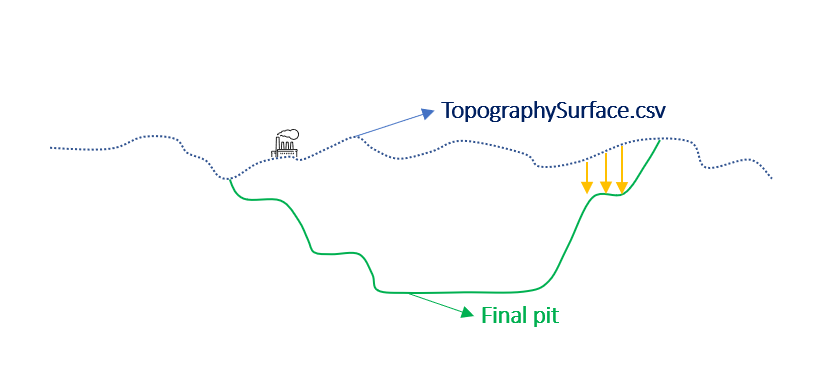

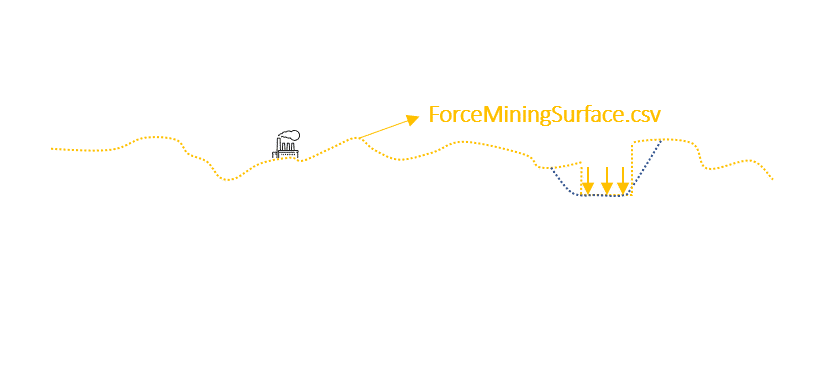

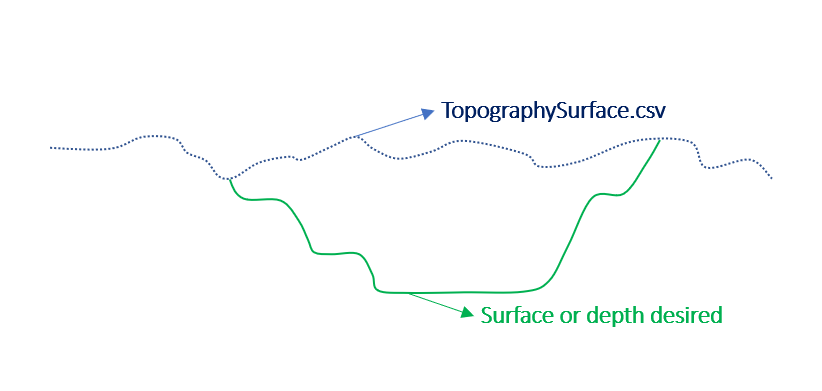

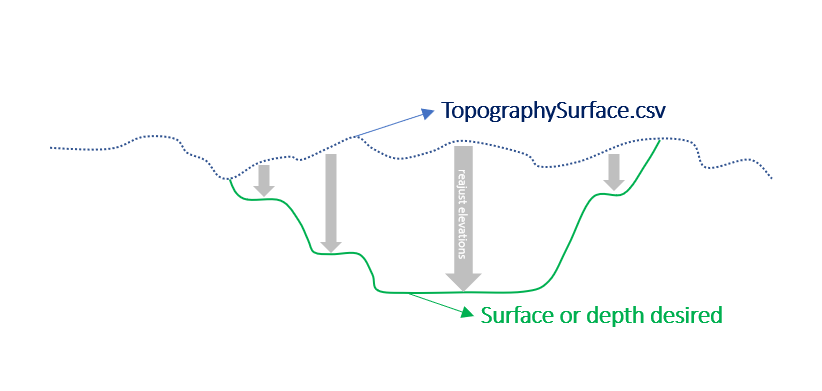

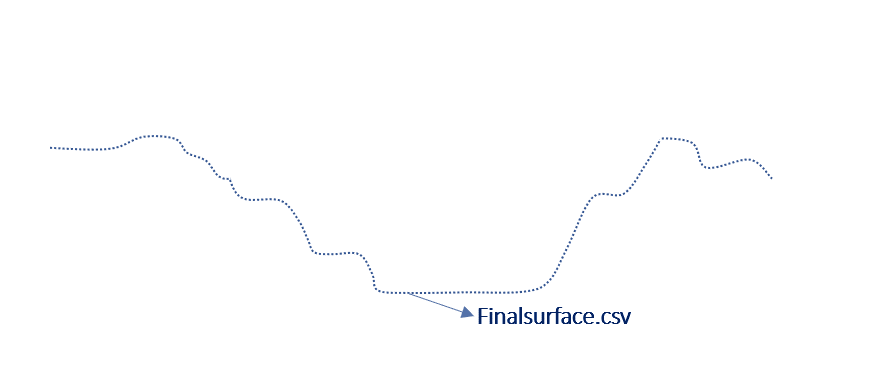

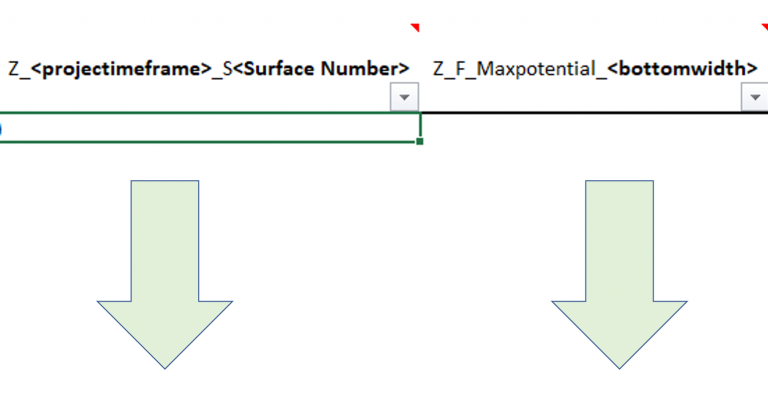

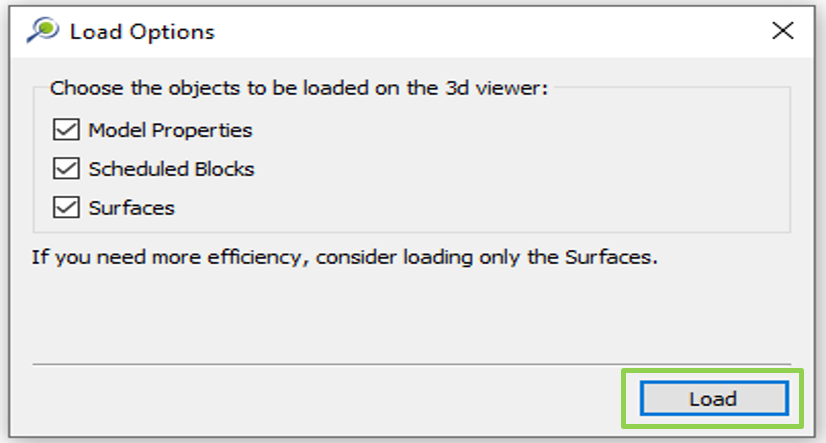

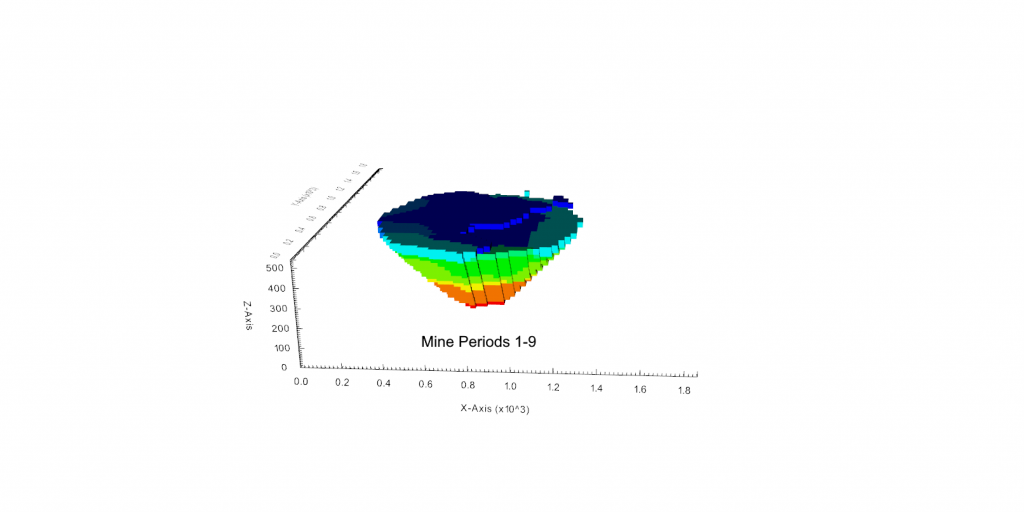

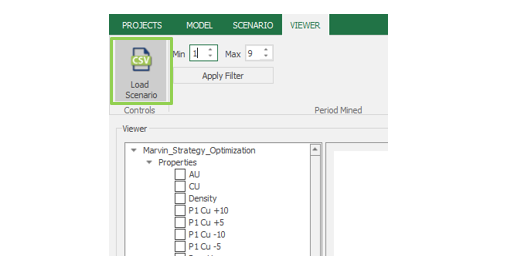

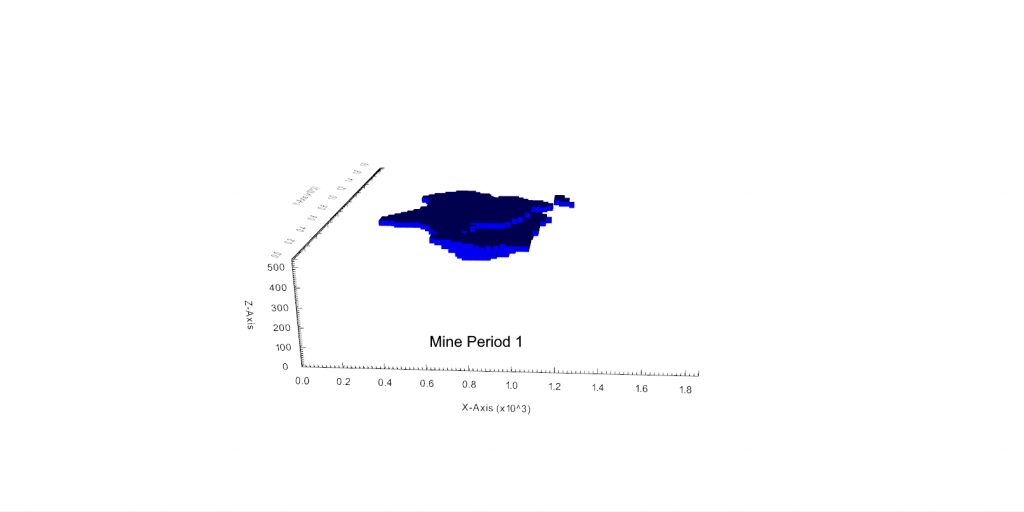

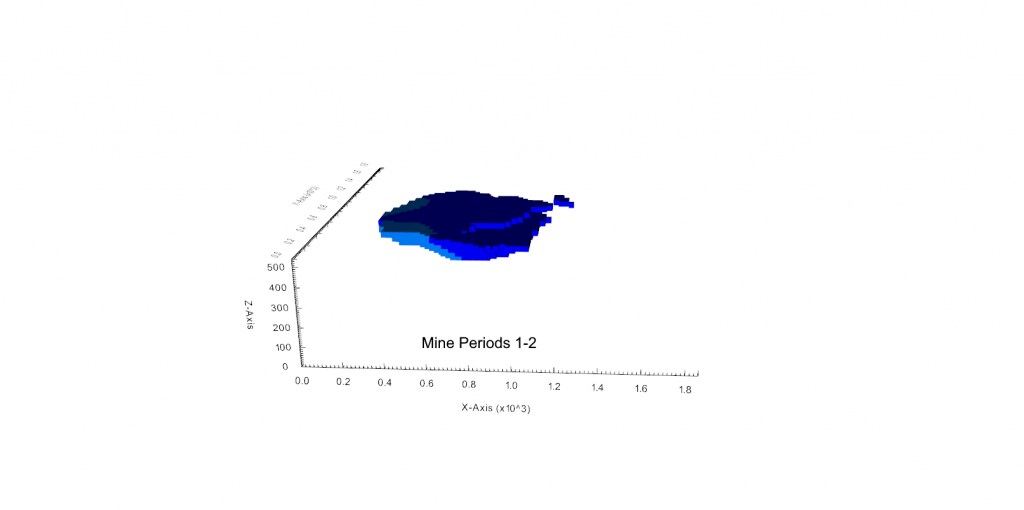

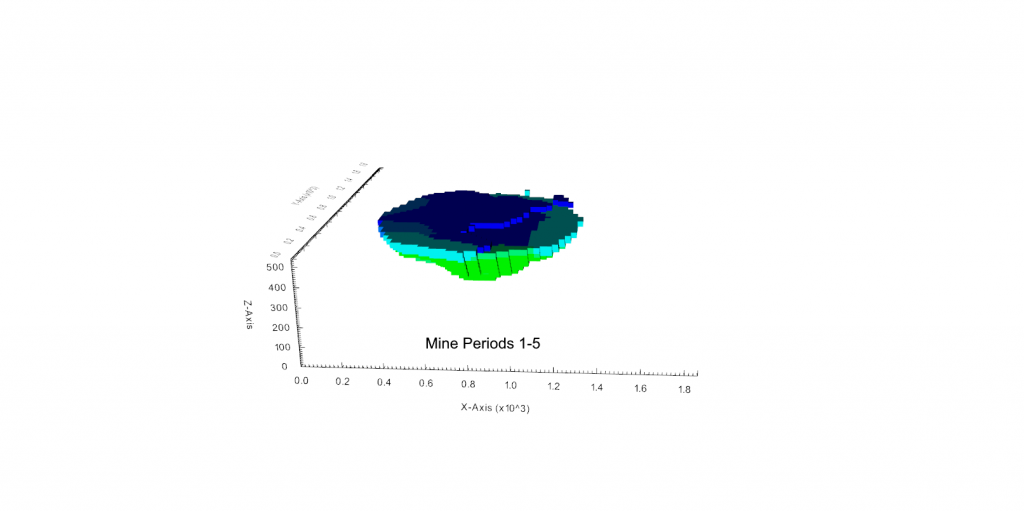

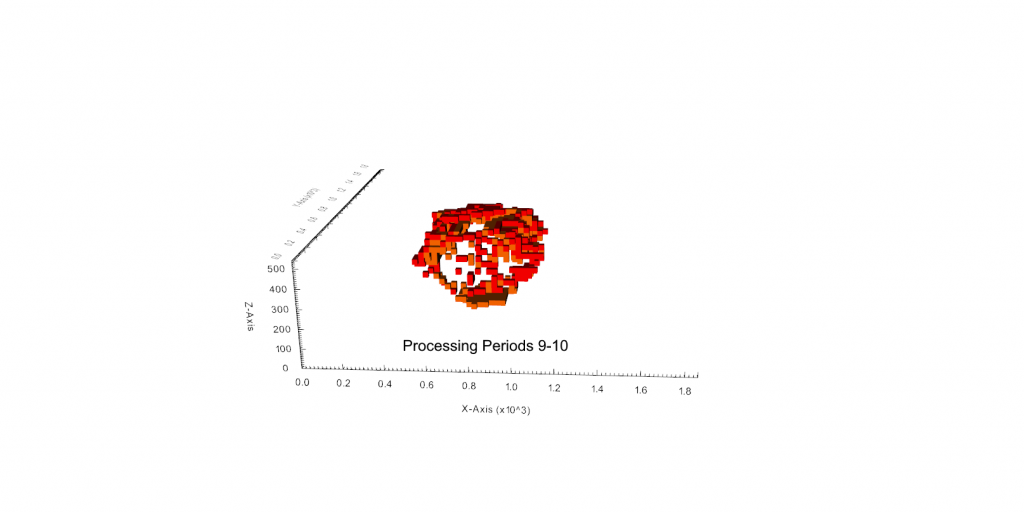

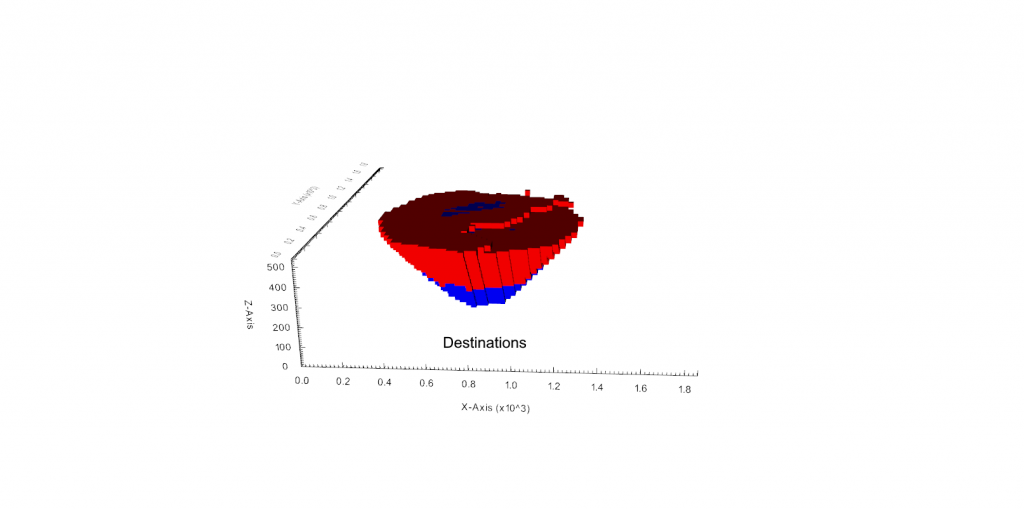

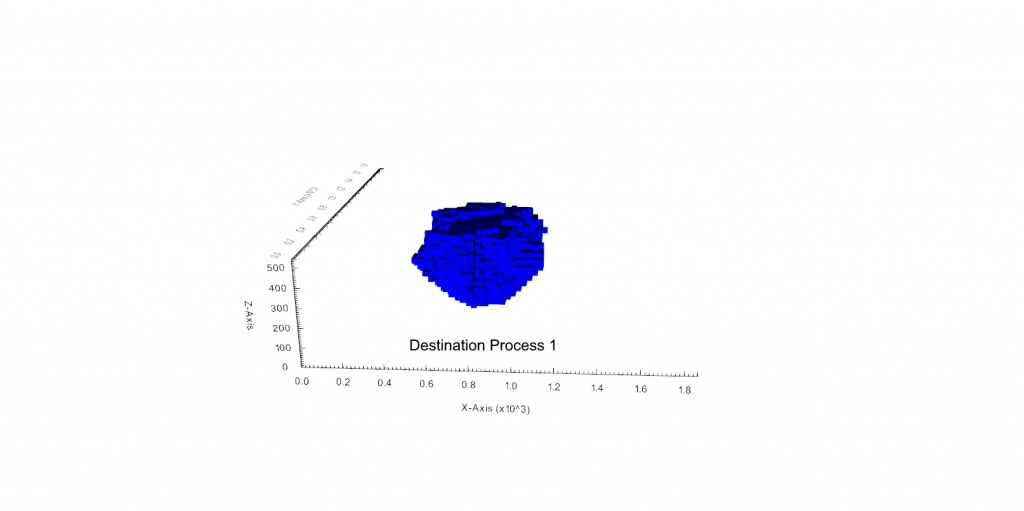

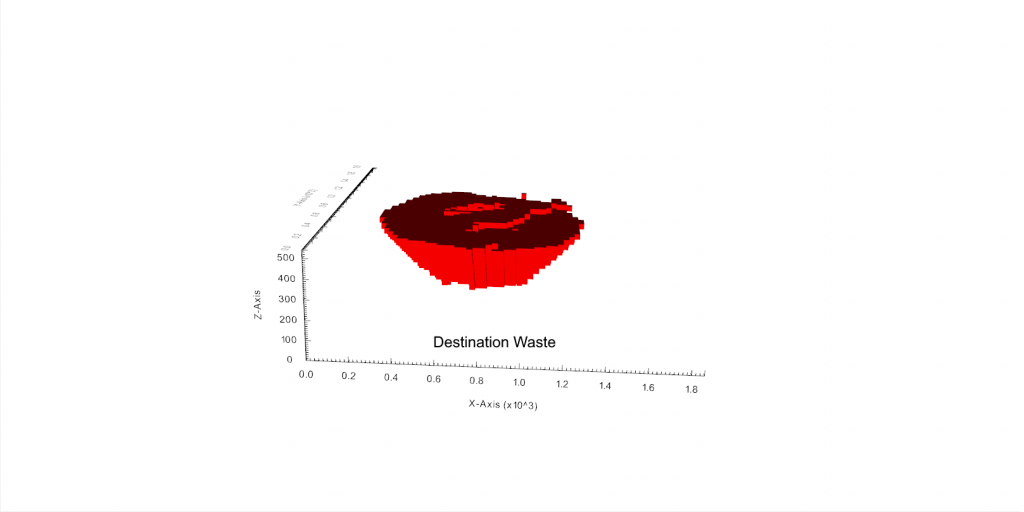

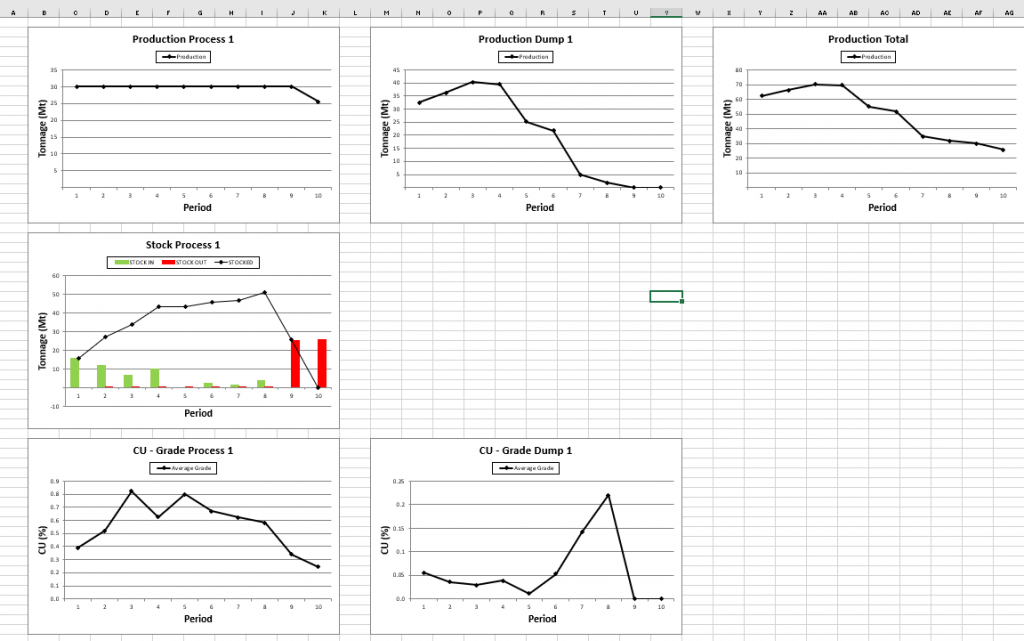

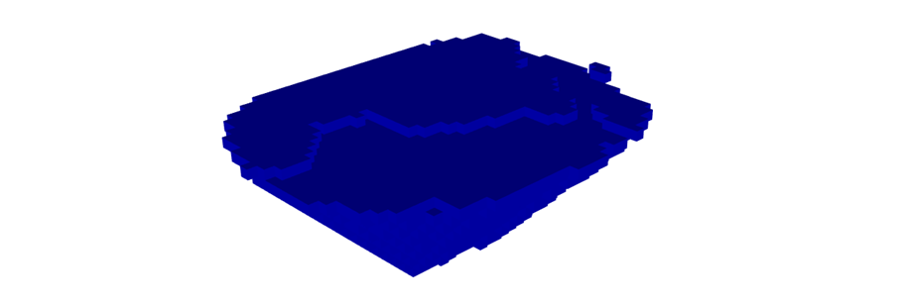

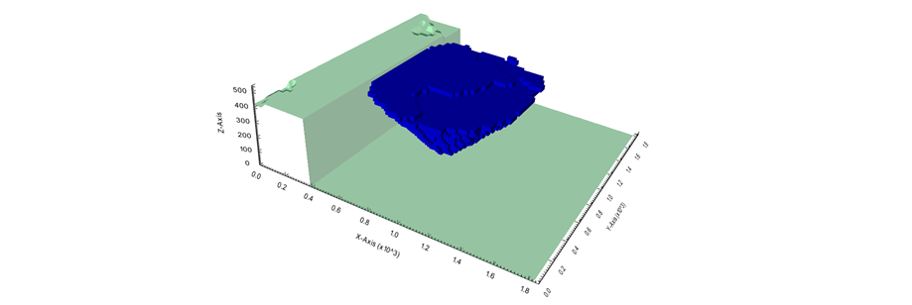

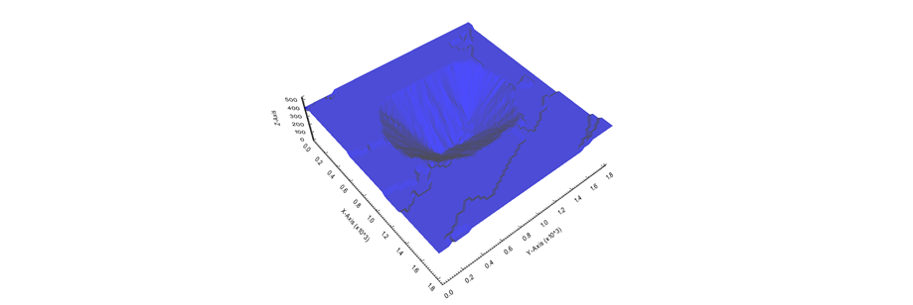

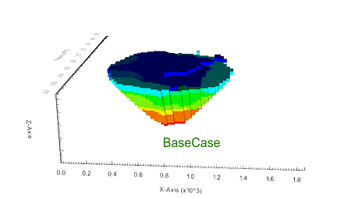

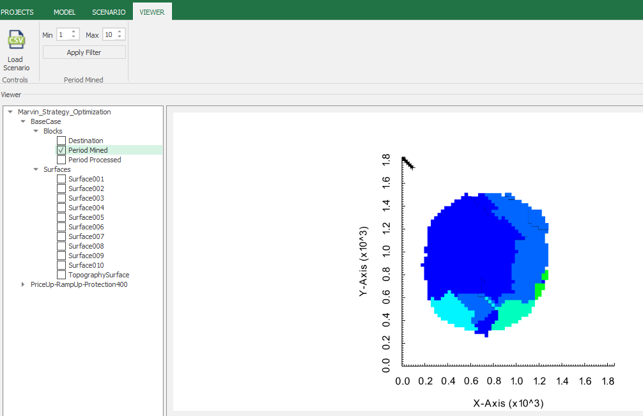

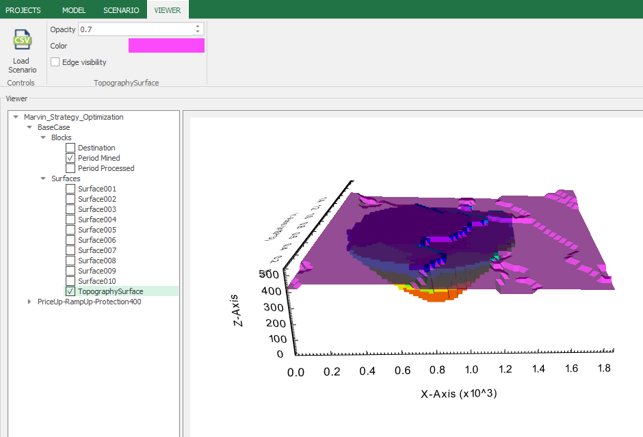

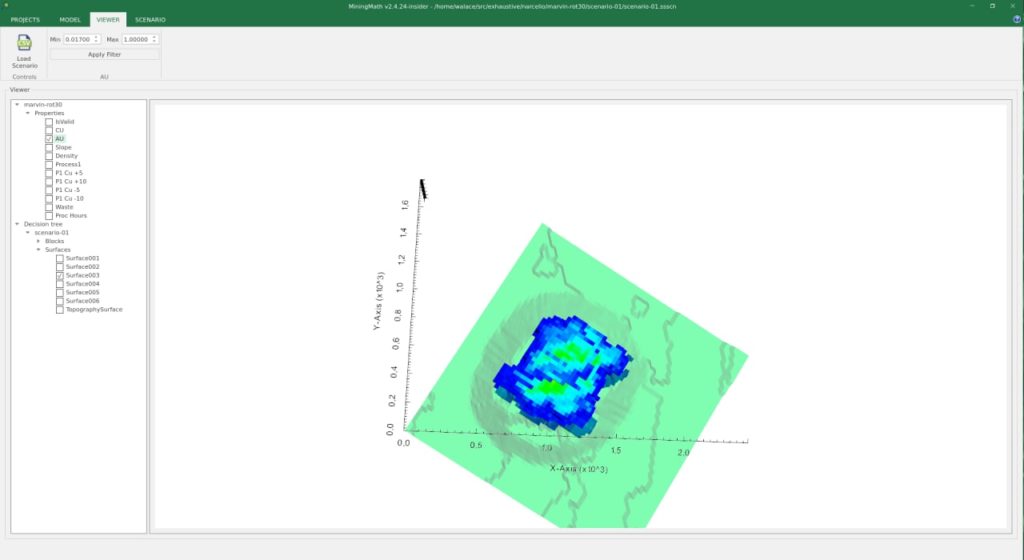

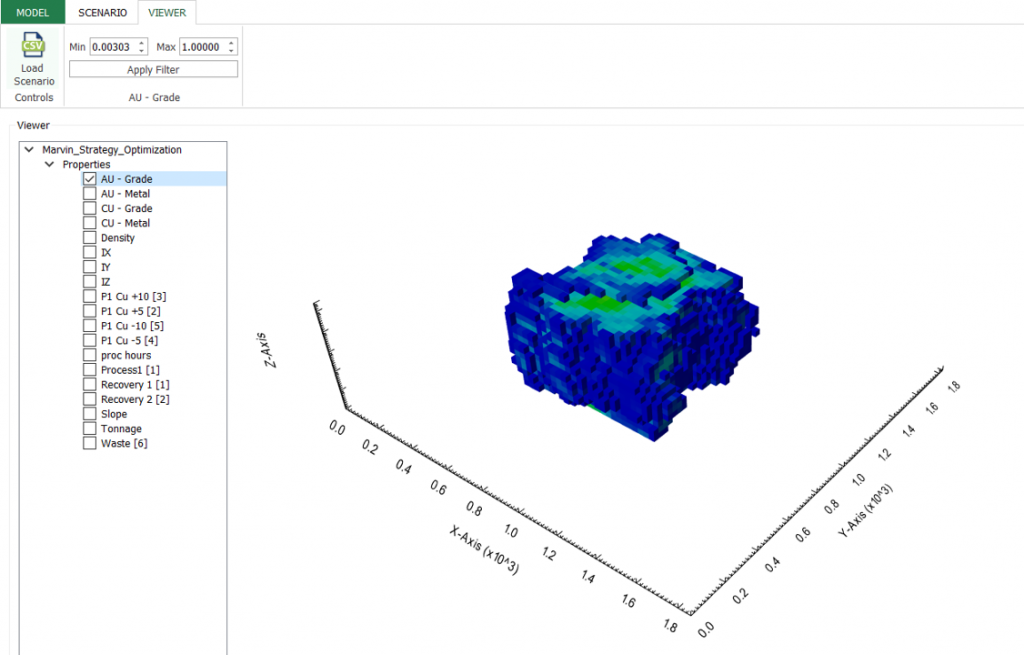

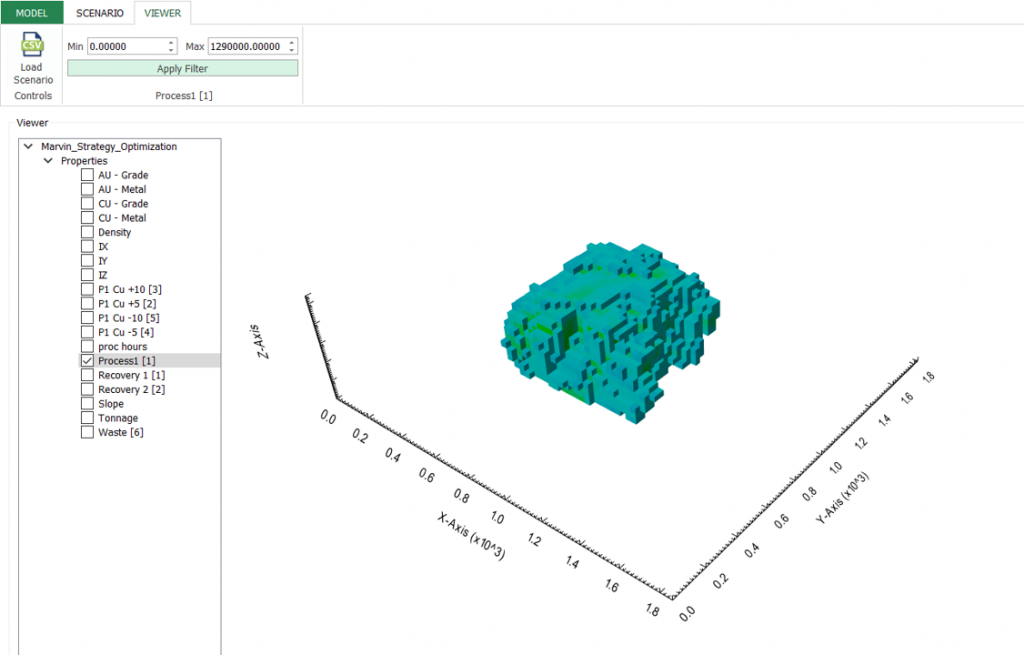

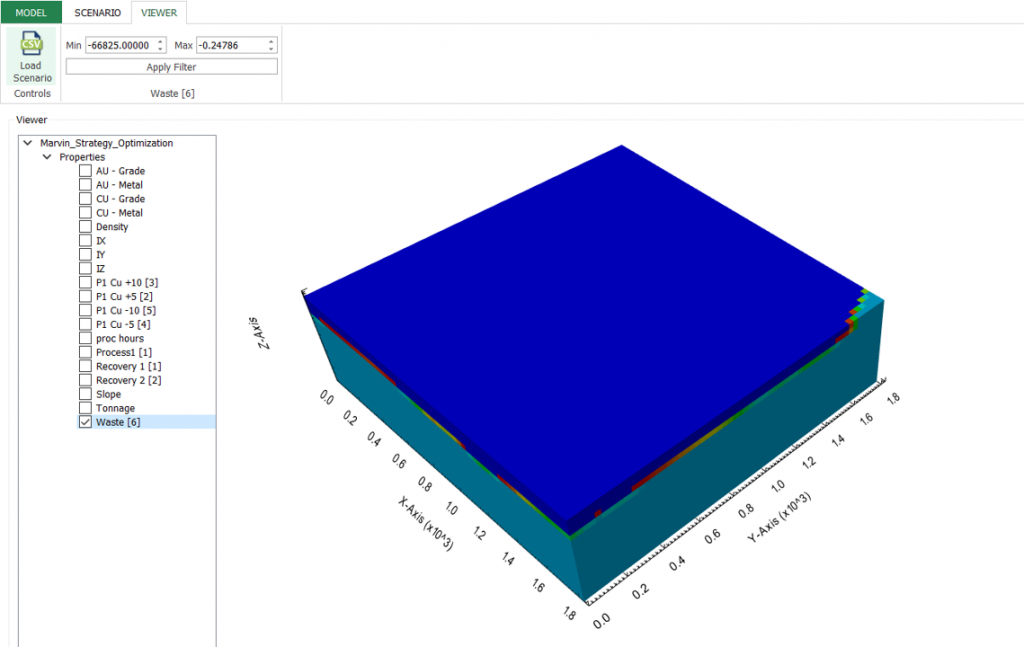

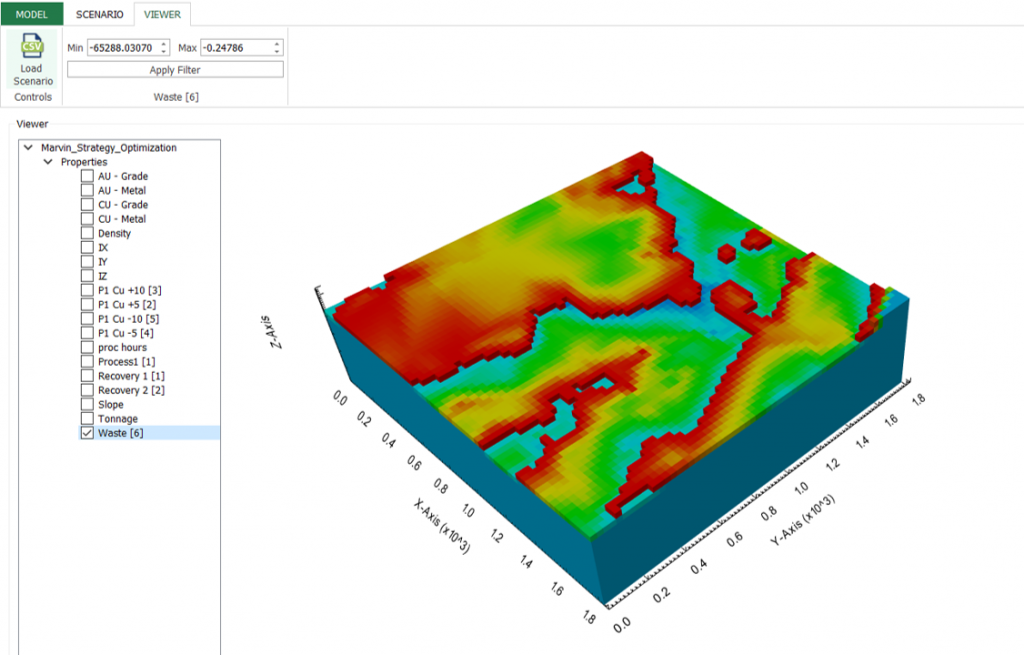

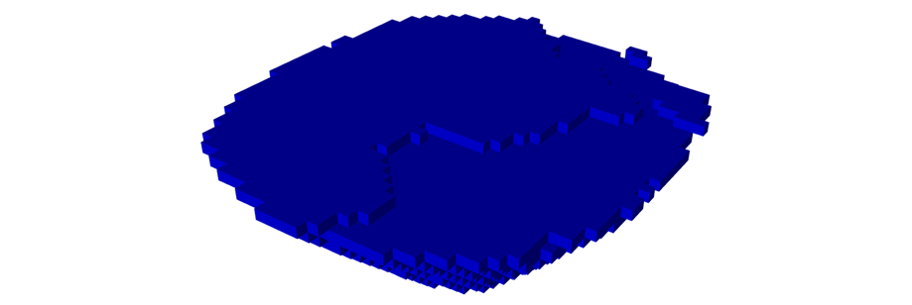

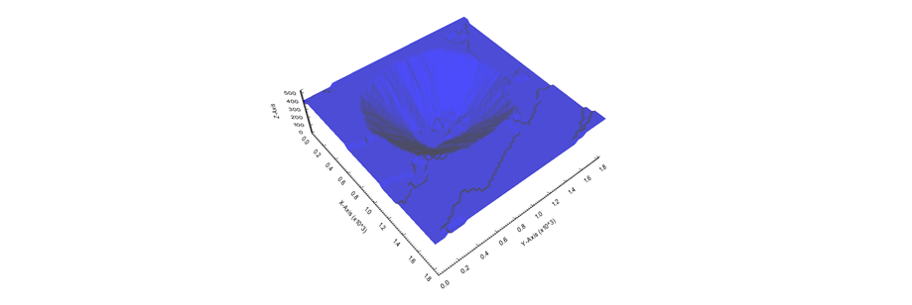

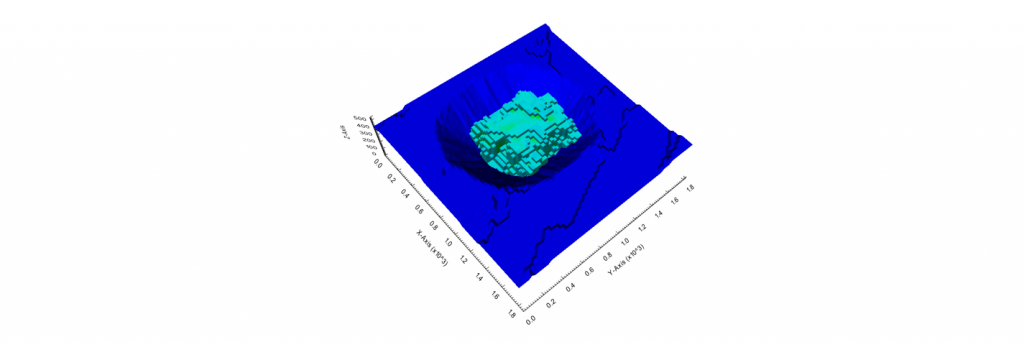

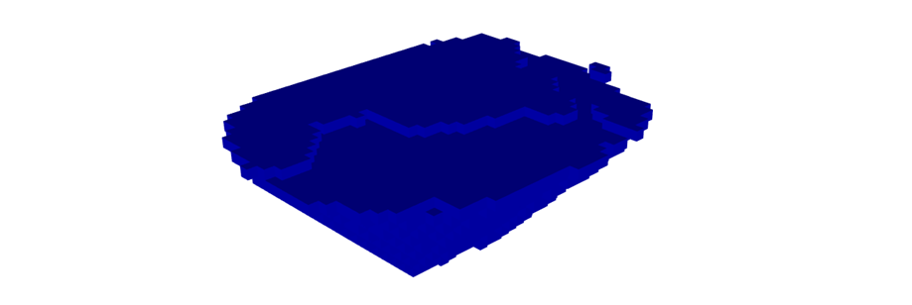

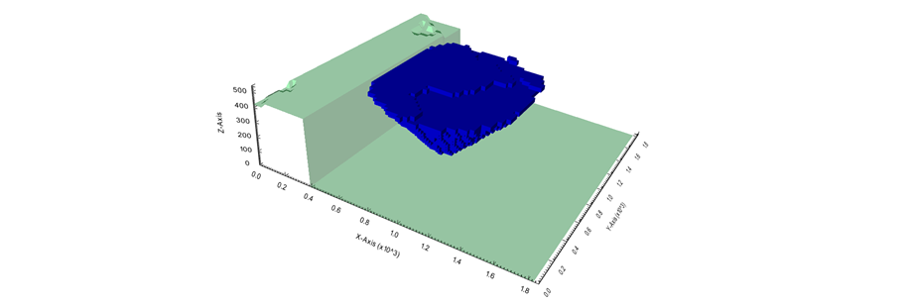

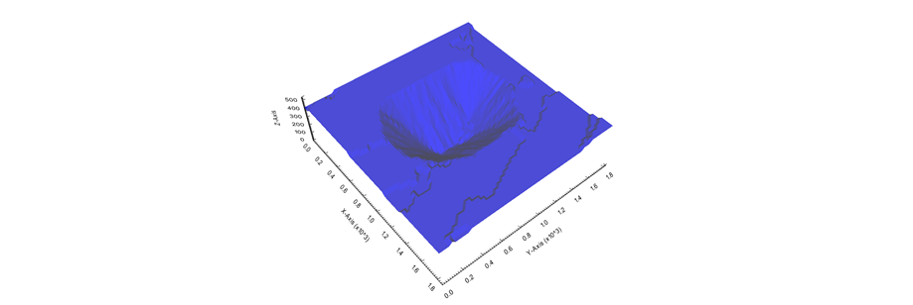

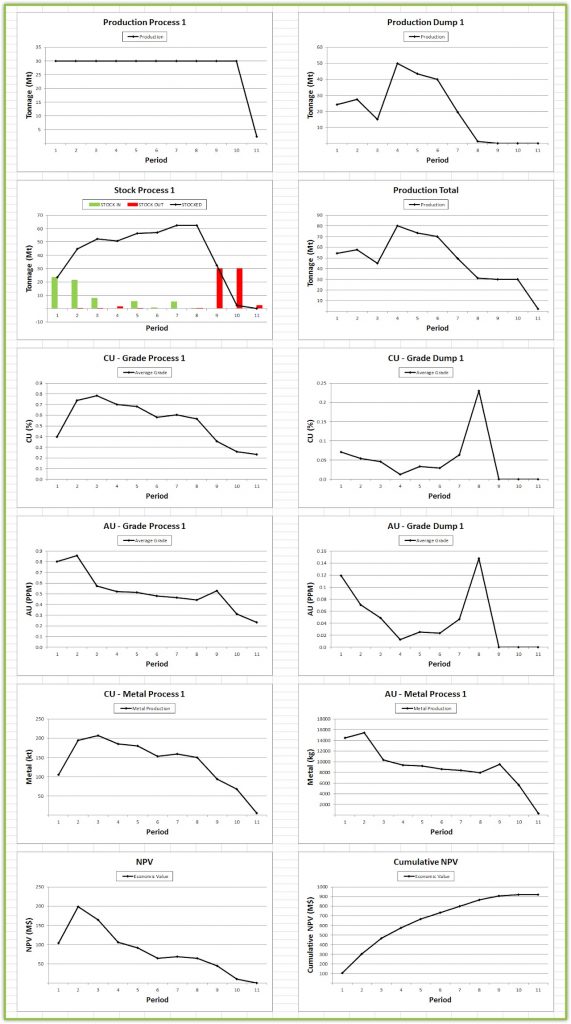

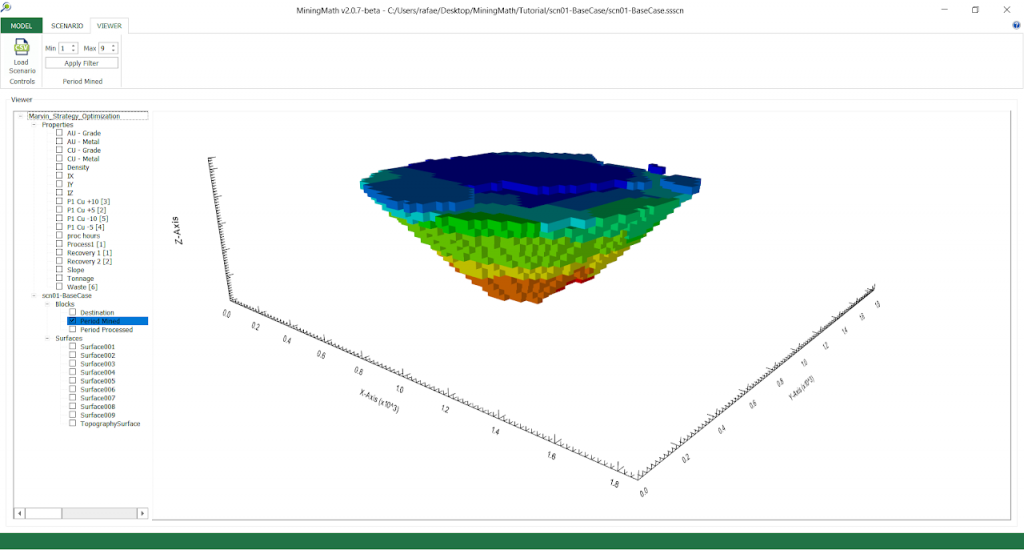

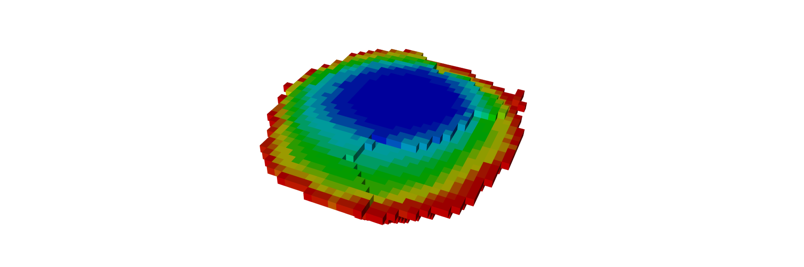

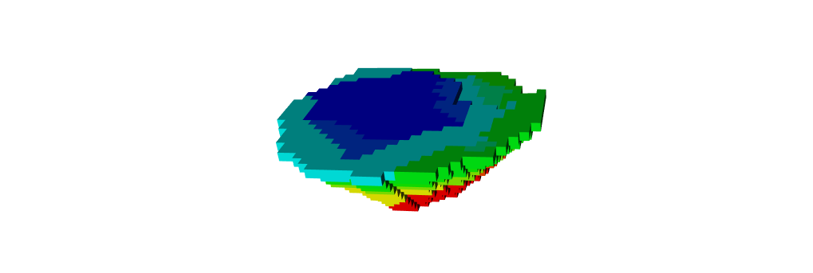

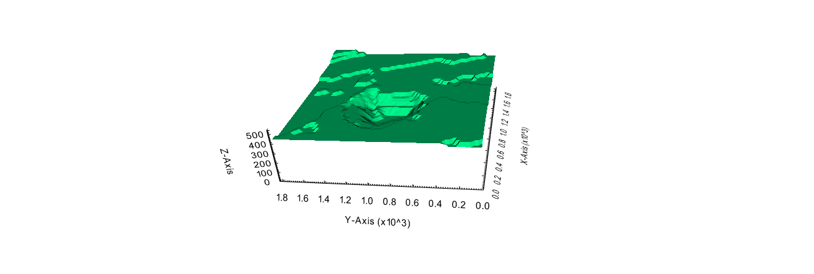

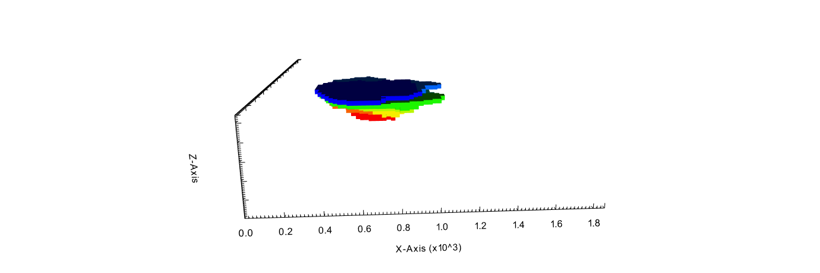

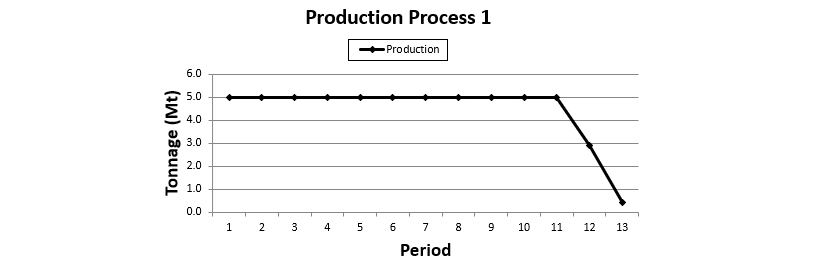

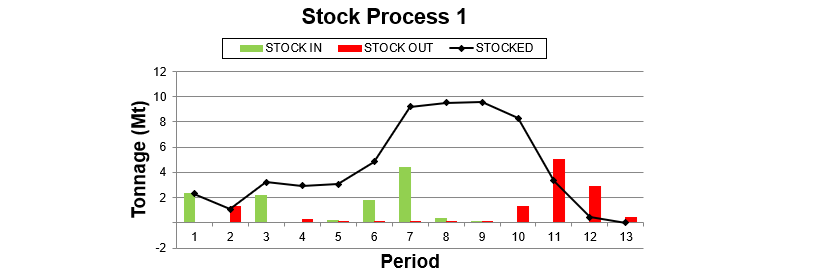

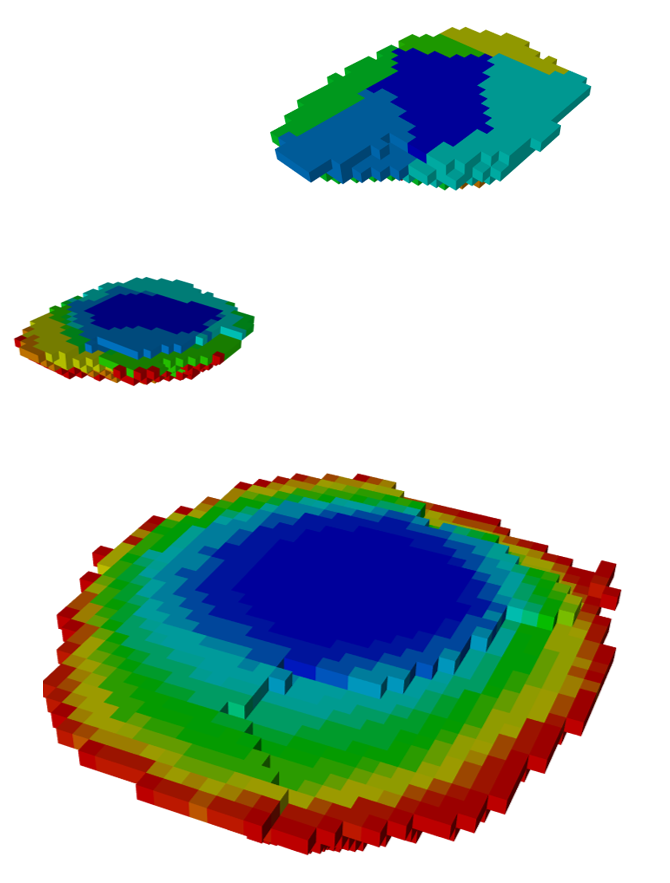

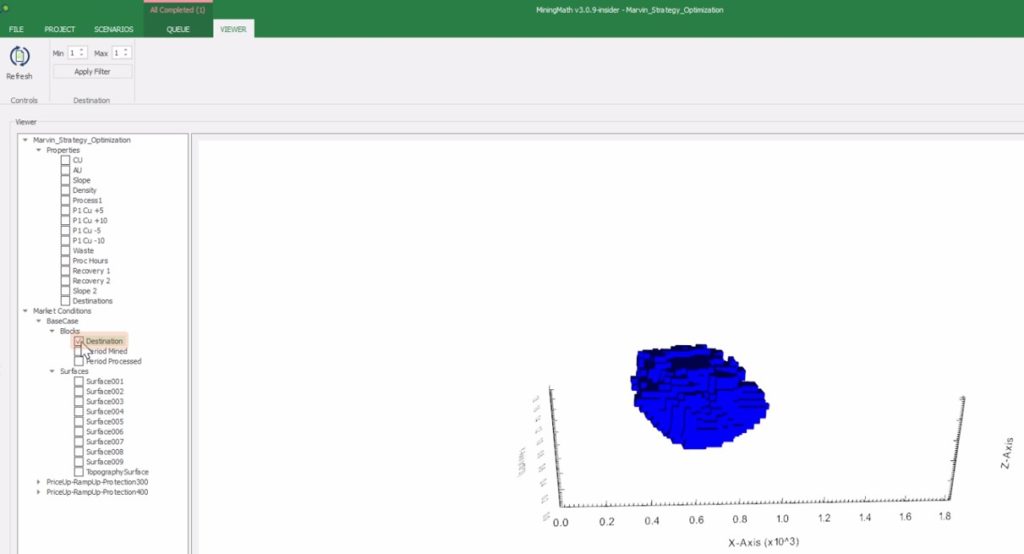

Output files and 3D viewer: by default, MiningMath generates an Excel report summarizing the main results of the optimization. It also creates outputs of mining sequence, topography, and pit surfaces in

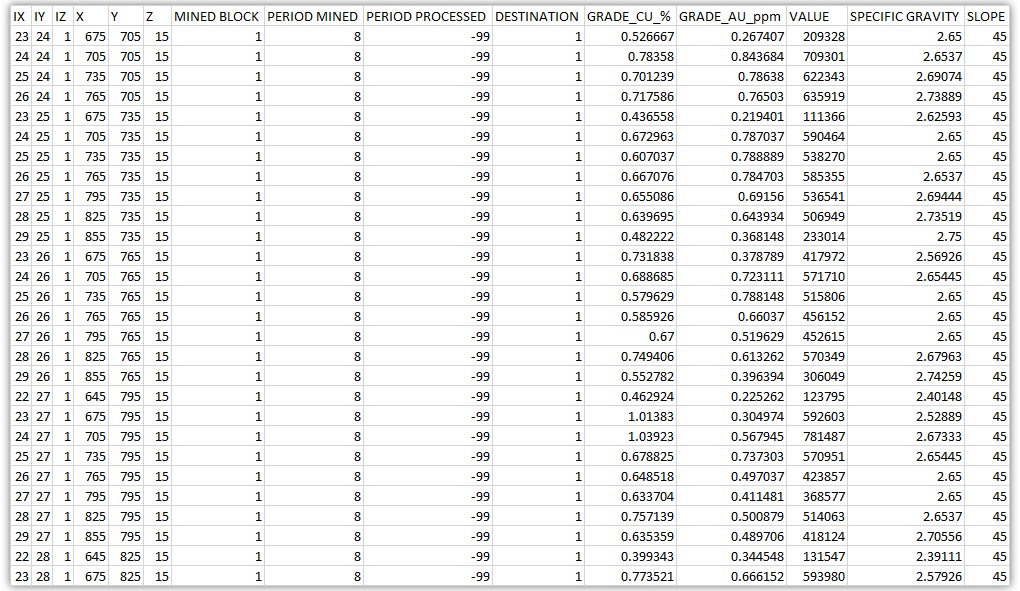

csvformat so that you can easily import them into other mining packages. The 3D viewer enables a view of your model from different angles.Export model: export your model as a

csvfile. This can be used in new scenarios or imported in other mining packages.

Extensive set-up

MiningMath offers a lot of customization. You might use pre-defined scenarios to learn with standard parameters. Otherwise, the following pages of the knowledge base detail several important parameters that might need to be fine tuned in your project.

Advanced content

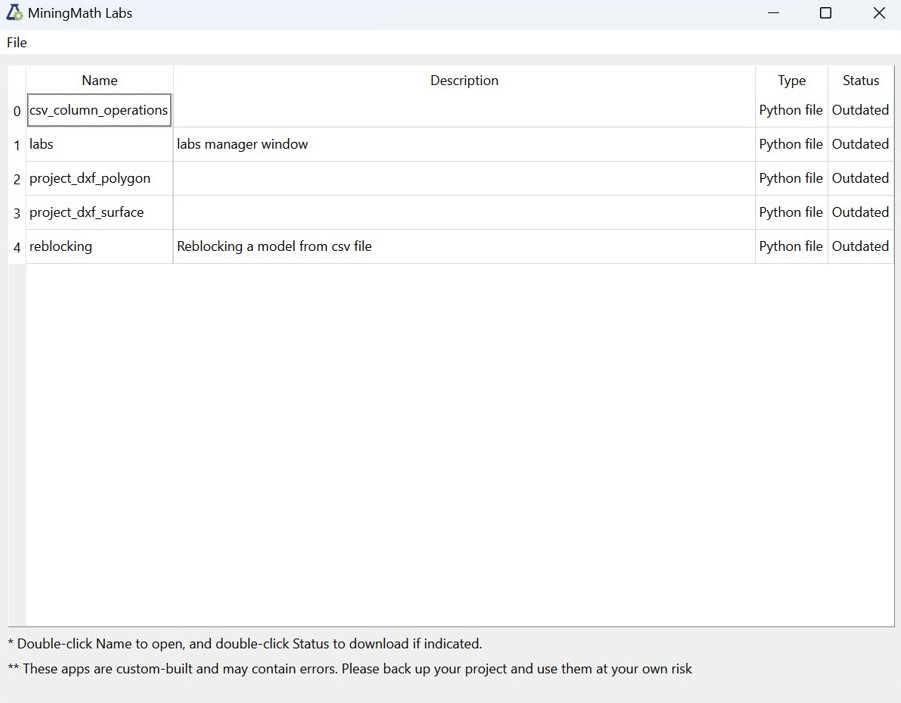

Complex projects might need advanced configurations or advanced knowledge in certain topics. The following pages cover some subjects considered advanced in our knowledge base.

Theory

In order to understand the theory behind MiningMath’s algorithm, a set of pages is provided to describe mathematical formulations, pseudo-code, and any rationale to justify the software design.

Workflows

ManingMath acknowledges and supports different workflows. This knowledge base provides a set of articles aimed at showing how MiningMath can be integrated into other workflows or have its results used by different mining packages.

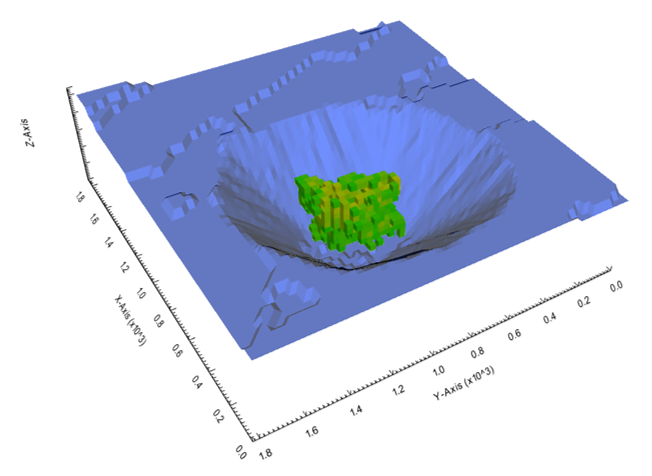

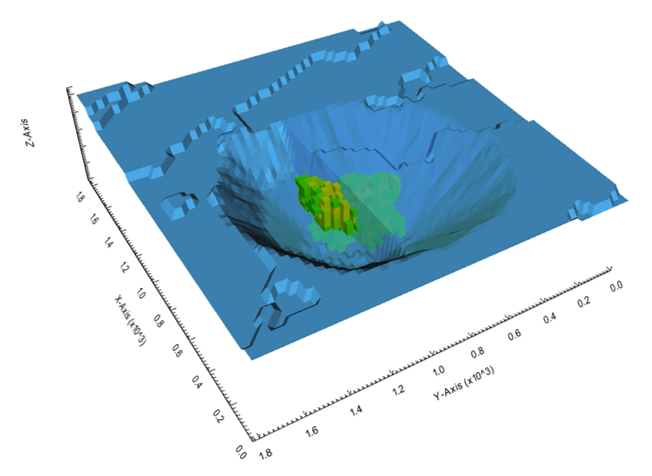

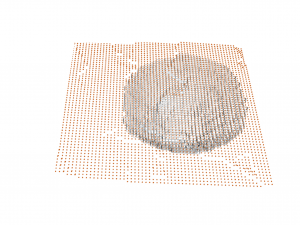

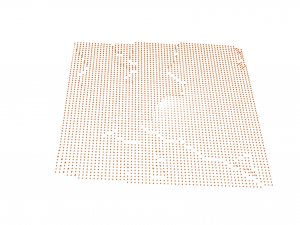

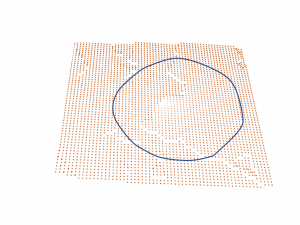

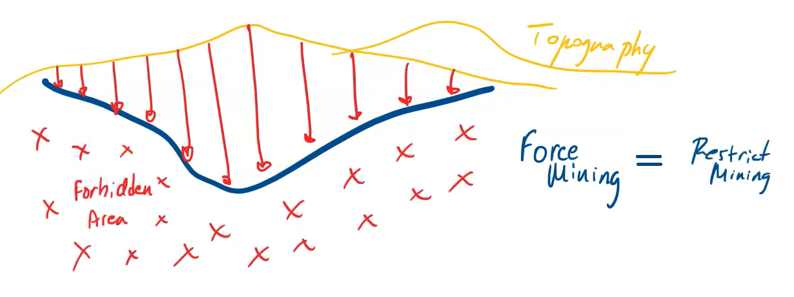

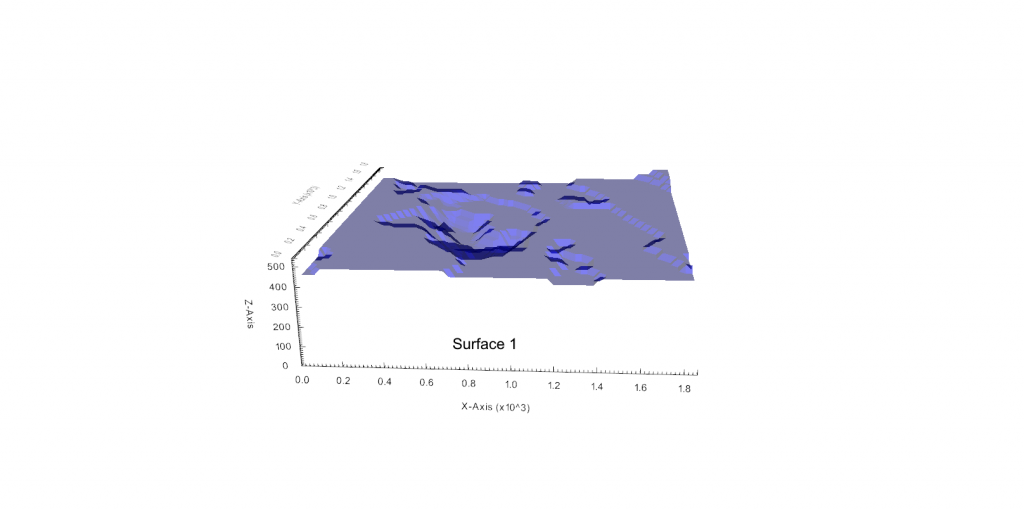

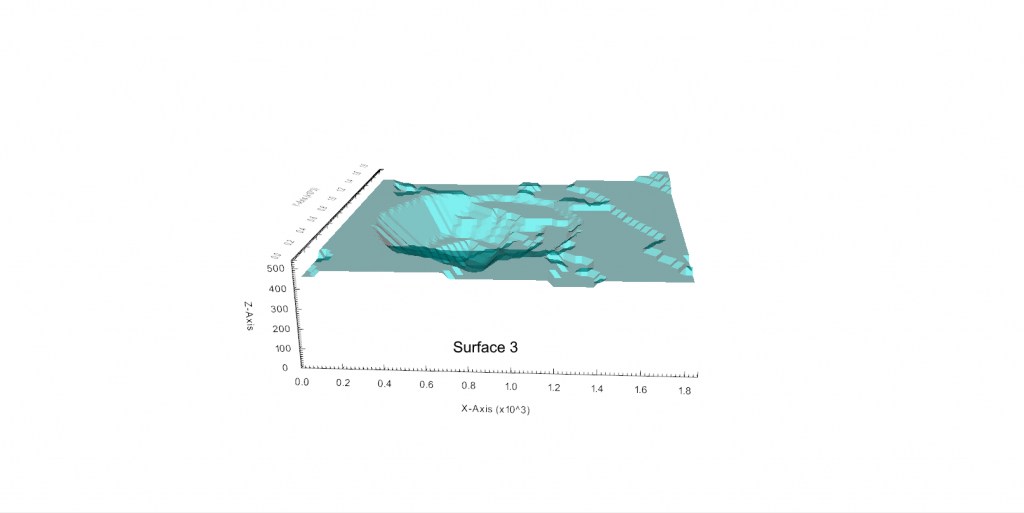

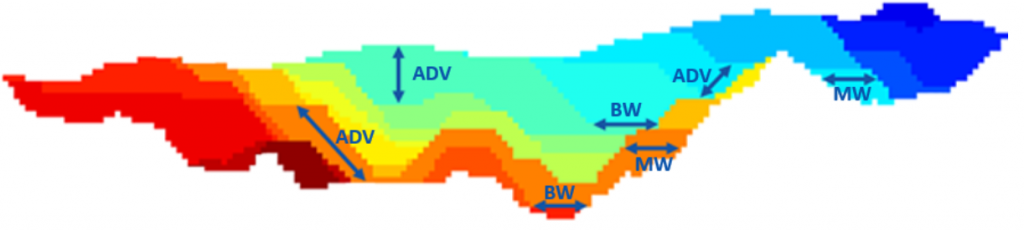

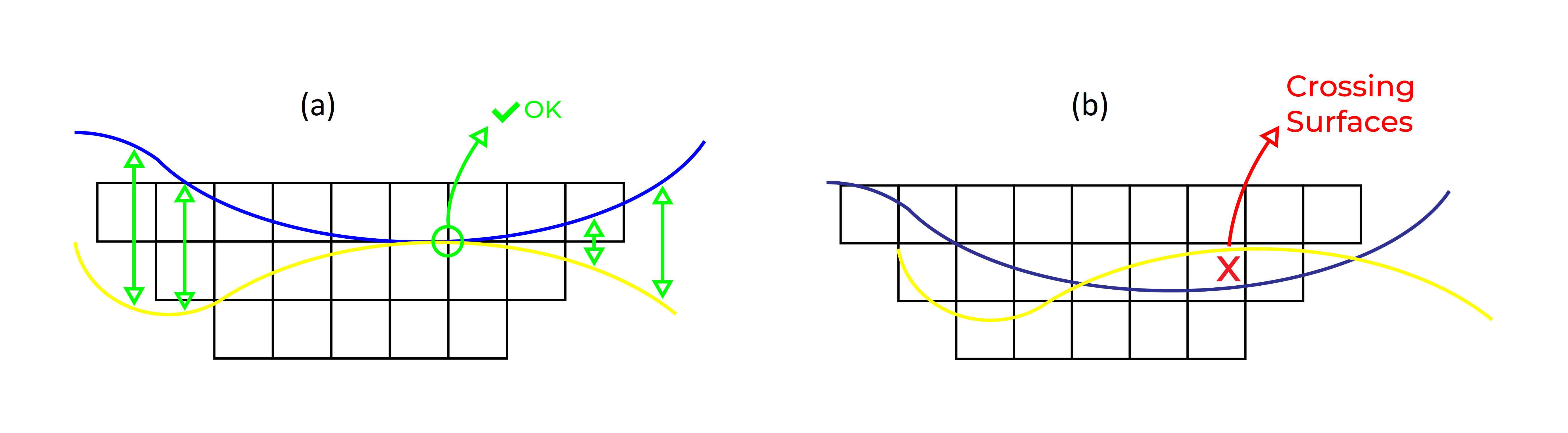

Figure 3: Two surfaces (blue and yellow): a) not crossing each other and respecting constraint (2); b) crossing each other and not respecting constraint (2).[/caption]

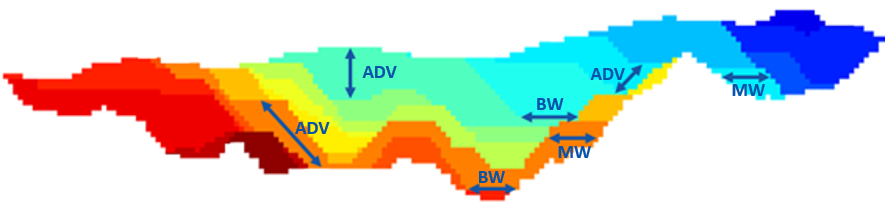

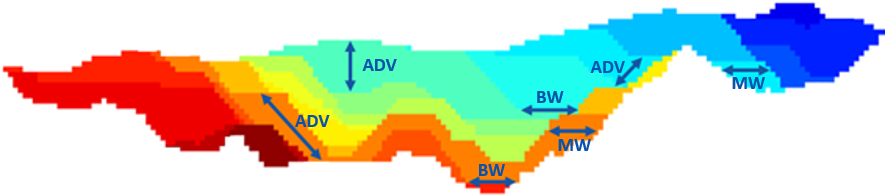

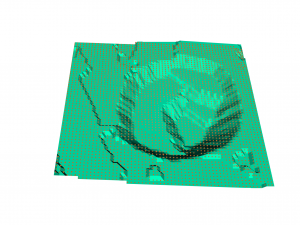

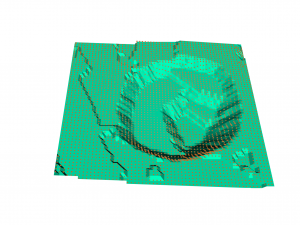

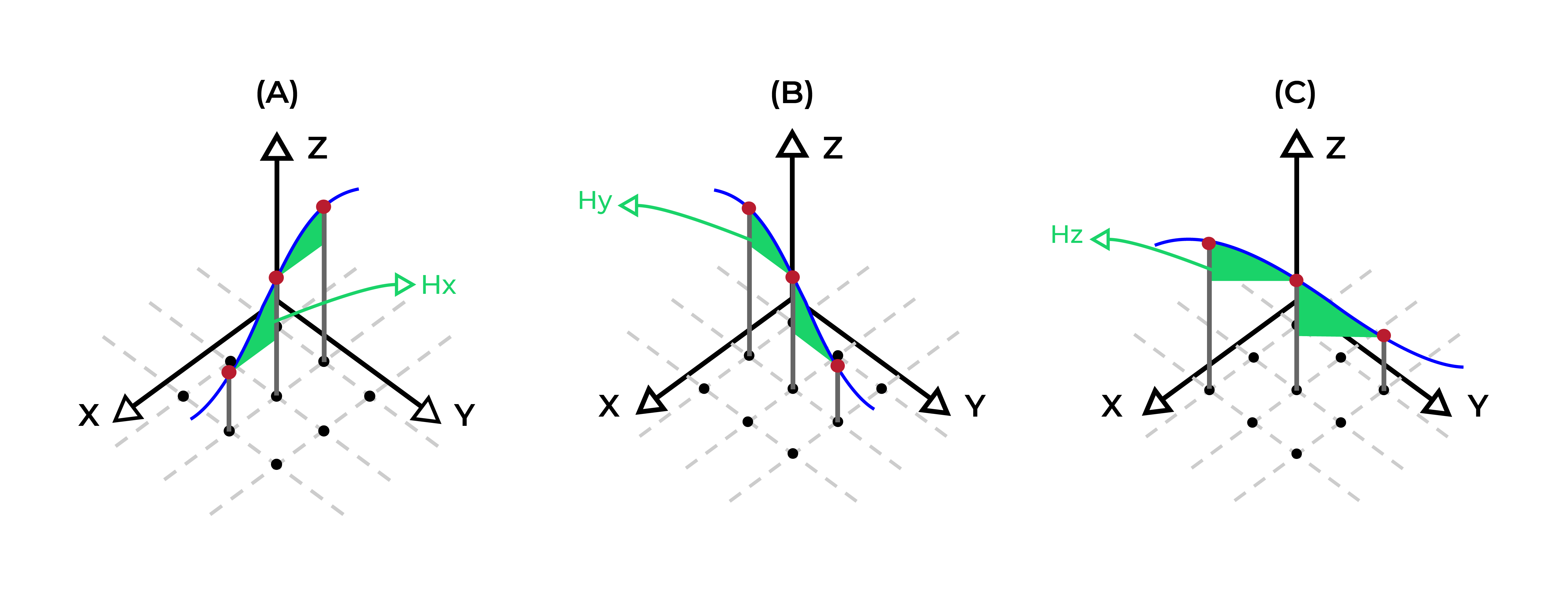

Figure 3: Two surfaces (blue and yellow): a) not crossing each other and respecting constraint (2); b) crossing each other and not respecting constraint (2).[/caption] Figure 4: Maximum allowed difference (Hx, Hy, and Hd) in elevation between adjacent cells in contact laterally in the x direction (a), in contact laterally in the y direction (b), and in contact diagonally (c).[/caption]

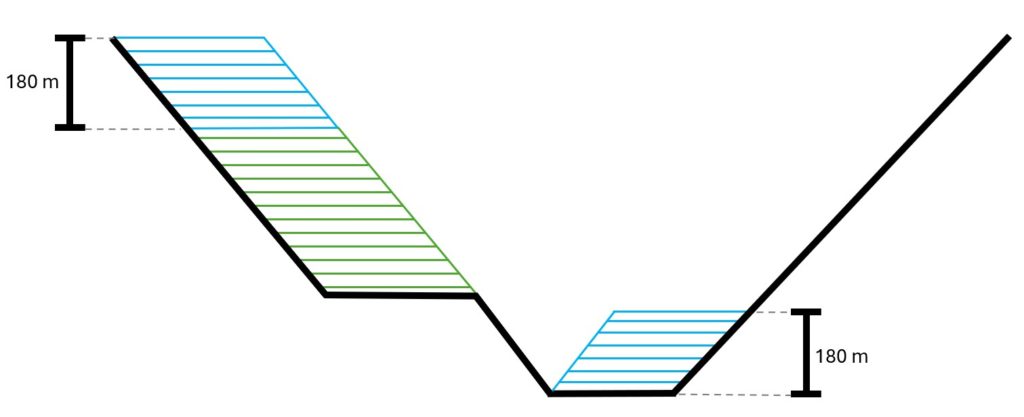

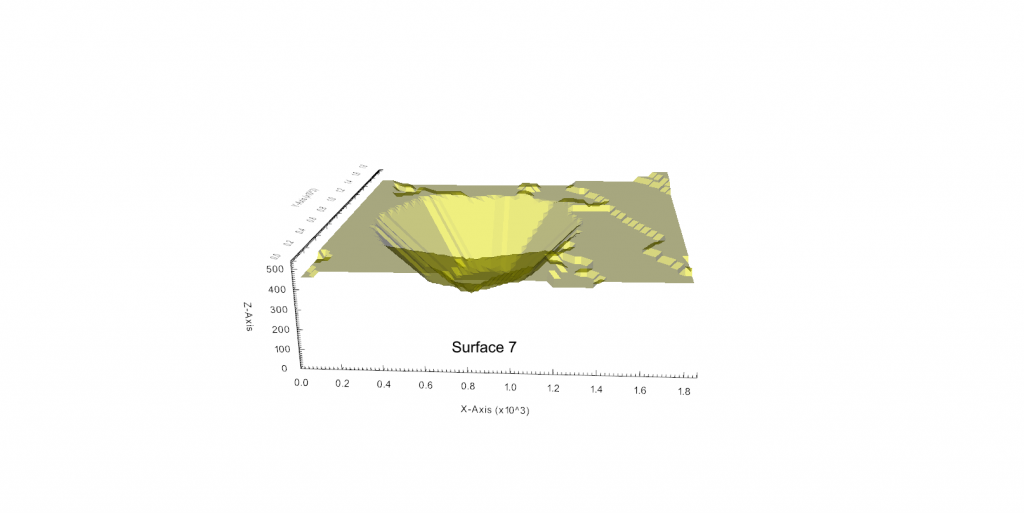

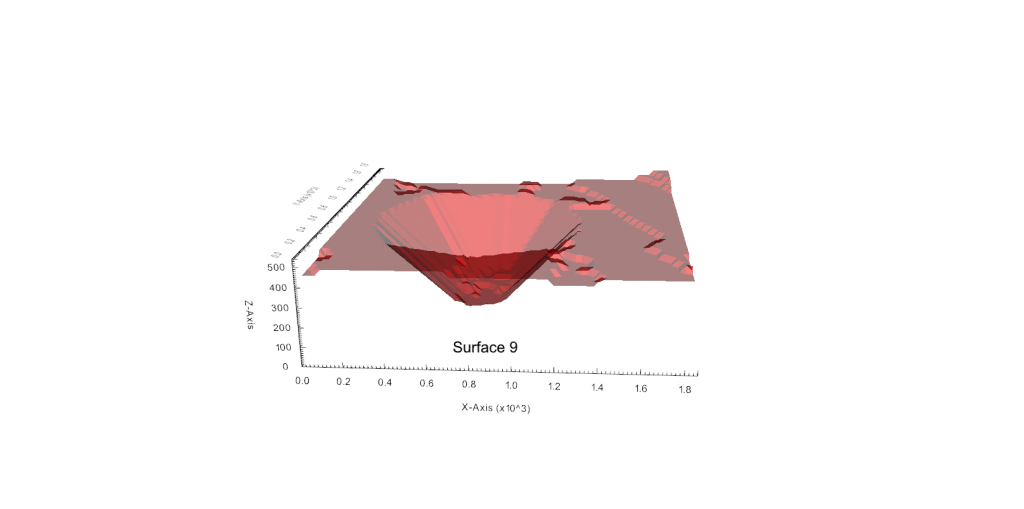

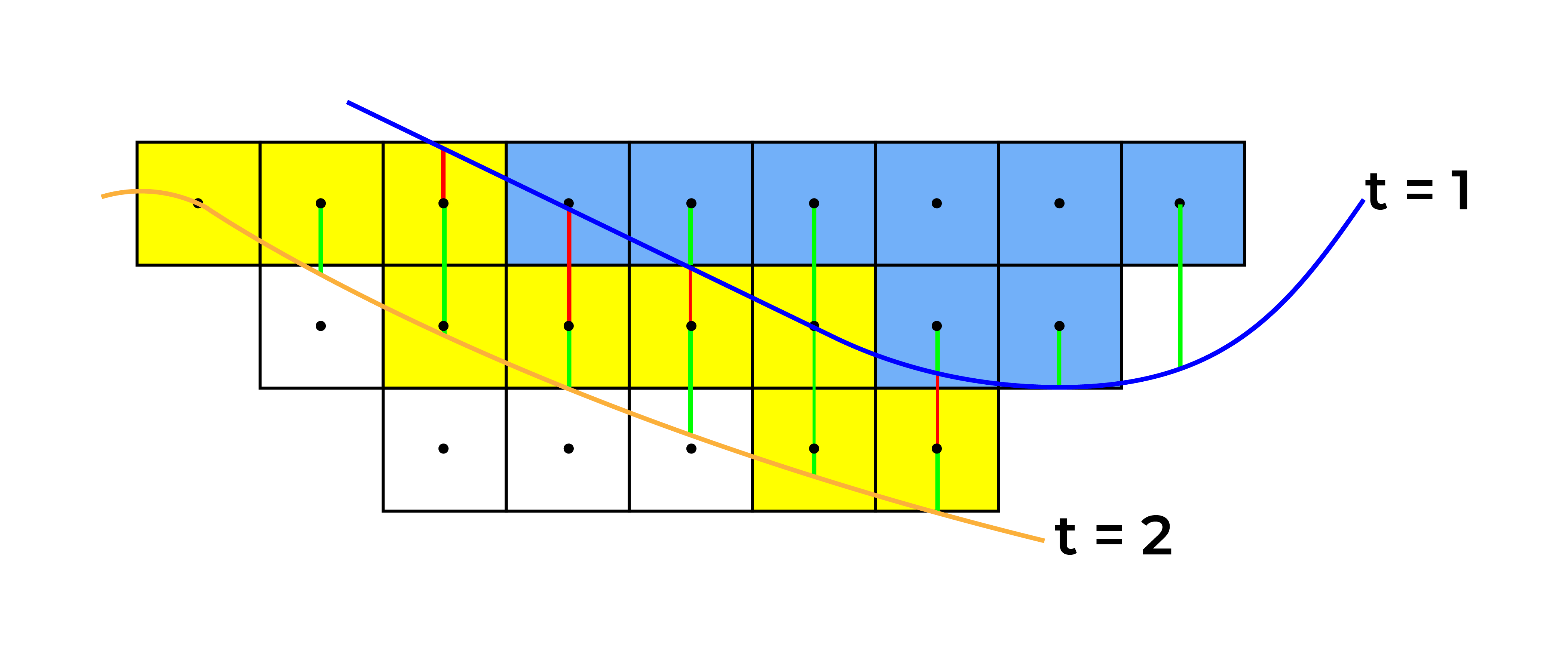

Figure 4: Maximum allowed difference (Hx, Hy, and Hd) in elevation between adjacent cells in contact laterally in the x direction (a), in contact laterally in the y direction (b), and in contact diagonally (c).[/caption] Figure 5: Distance between centroids above surfaces (green lines) and below surfaces (red lines) respecting constraints (6) and (7). Blue blocks are mined in period 1, while yellow blocks are mined in period 2.[/caption]

Figure 5: Distance between centroids above surfaces (green lines) and below surfaces (red lines) respecting constraints (6) and (7). Blue blocks are mined in period 1, while yellow blocks are mined in period 2.[/caption]

“The software that could revolutionize mine planning”

“The software that could revolutionize mine planning” How digital innovation can improve mining productivity

How digital innovation can improve mining productivity Digital Transformation—The future of Mining

Digital Transformation—The future of Mining A tool for these times

A tool for these times Mine Optimizations and SimSched DBS is a friend of yours now. SimSched DBS is the most powerful tool to achieve and compare NPV results of the pit.

Mine Optimizations and SimSched DBS is a friend of yours now. SimSched DBS is the most powerful tool to achieve and compare NPV results of the pit.